A supercooled protein folds unexpectedly

Human bodies have a narrow range of temperatures at which they function properly. Unsurprisingly, proteins behave similarly: At ambient temperatures they fold as needed for their biological purposes, but if they get too hot or too cold, their structures begin to come apart. The details of what happens to proteins away from their conformational sweet spot, and how or why it happens, could provide insight into how they manage to find their functional forms at physiological conditions.

Daniel Kozuch, Frank Stillinger, and Pablo Debenedetti

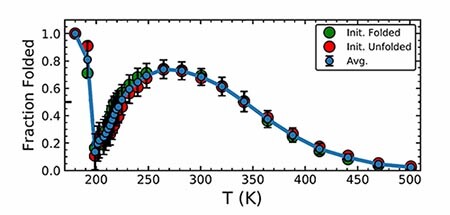

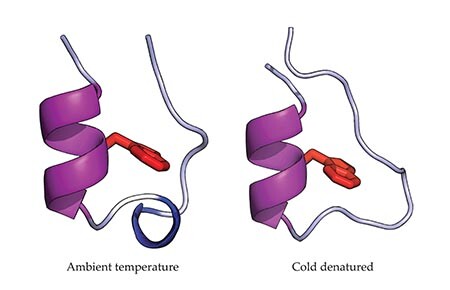

The supercooled folded structure was remarkably similar, though not identical, to that at ambient temperature. Denaturation of Trp-cage by cooling is characterized by the unfolding of a small helix (see second figure), and that feature returned at sufficiently low temperatures. Additionally, the helix formation was accompanied by the development of a more compact hydrophobic core.

To seek an explanation for the structural difference, the researchers turned to the surrounding water molecules. The temperature at which the protein refolded was the same temperature at which the water finished transitioning from a high- to a low-density state. The water remained liquid, so the solvent had no long-range order, but on short length scales the molecules became tetrahedrally coordinated (see the article by Pablo Debenedetti and Gene Stanley, Physics Today, June 2003, page 40

Although proteins don’t run the risk of becoming supercooled in vivo, their behavior at below-freezing temperatures may have implications for cryo-microscopy and cryo-preservation techniques. (D. J. Kozuch, F. H. Stillinger, P. G. Debenedetti, J. Chem. Phys. 151, 185101, 2019