A quantum squeezed state of a mechanical resonator has been realized

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2967

The uncertainties imposed by quantum mechanics, though unavoidable, take the form of a trade-off: It’s always possible, at least in theory, to reduce the uncertainty in a parameter of interest (a particle’s position, say) at the expense of increasing the uncertainty of something else (its momentum).

In optics, the trade-off gives rise to so-called squeezed states of light, which can be constructed, for example, with lower uncertainty in their amplitude and higher uncertainty in their phase, or vice versa. More generally, if the waveform is written as Xcos(ωt) + Ysin(ωt), where t is time and ω is the wave’s frequency, then X and Y, called the quadratures, are the requisite pair of noncommuting quantities whose uncertainties can be manipulated. The ability to produce squeezed light using nonlinear optics enables greater sensitivity in optical measurements such as those made by large interferometers (see Physics Today, November 2011, page 11

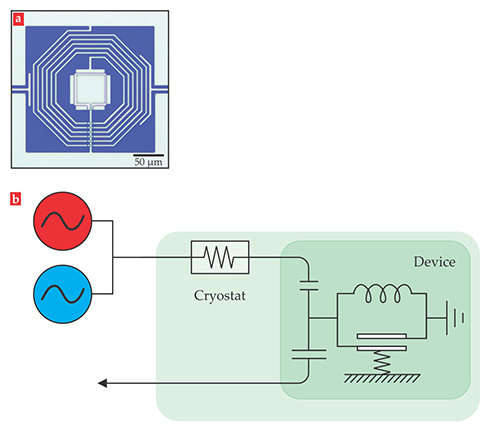

Now Caltech’s Keith Schwab and collaborators have achieved the long-standing goal of similarly squeezing the quantum state of a micron-scale mechanical resonator. 1 In their device, shown in figure 1a, the center-square capacitor and the spiral-wire inductor form an LC circuit with a resonant frequency of 6.2 GHz. The top plate of the capacitor is free to move, with a vibrational frequency of 3.6 MHz. Through the coupling between the circuit and mechanical resonator, the researchers squeezed one quadrature of the mechanical resonator’s motion down to 80% of the quantum zero-point level.

Figure 1. Coupling between a mechanical resonator and an LC circuit allows engineering of the resonator’s quantum state. (a) In this optical micrograph, the center square is a parallel-plate capacitor, and the spiral wire is an inductor. The capacitor’s top plate, which has a vibrational degree of freedom, is also the mechanical resonator. Capacitors at left and right provide input and output coupling. (b) Here, the same system is shown schematically. The device is cooled by a cryostat to 10 mK, and the circuit is then driven at its red-detuned and blue-detuned sideband frequencies, the difference and sum of the resonant frequencies of the circuit and the mechanical resonator. (Adapted from ref.

Fresh squeezed

A major obstacle to teasing out such a micromechanical system’s quantum character is that even at a chilly 10 mK, thermal fluctuations in the mechanical motion overwhelm quantum fluctuations by two orders of magnitude. (In contrast, optical modes at room temperature are in their quantum ground state.)

That’s where the coupled circuit comes in. As shown in figure 1b, motion of the mechanical resonator changes the capacitance of the parallel-plate capacitor. The circuit’s resonant frequency ωc thus acquires two sidebands at ωc ± ωm, where ωm is the mechanical frequency. (For a description of an equivalent system using an optical cavity instead of a circuit, see the article by Markus Aspelmeyer, Pierre Meystre, and Keith Schwab, Physics Today, July 2012, page 29

Driving the circuit at the so-called blue-detuned frequency ωc + ωm amplifies the mechanical oscillations: Each quantum of energy in the circuit can impart its excess energy to the resonator in the form of a phonon. Likewise, driving at the red-detuned frequency ωc − ωm removes energy from the mechanical resonator.

In 2011 John Teufel and colleagues at NIST used that technique to cool a micromechanical resonator into its quantum ground state.

2

(See Physics Today, September 2011, page 22

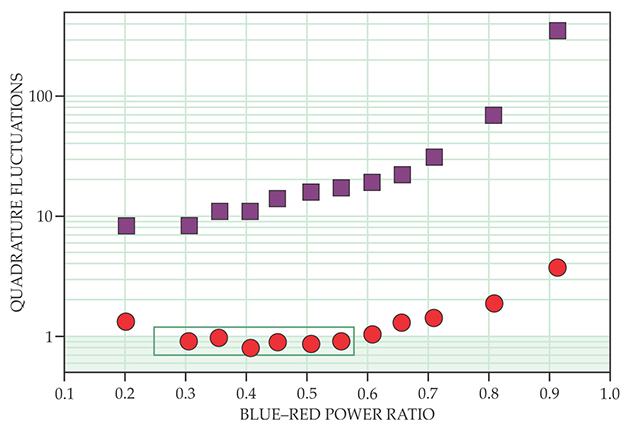

Verifying that the scheme works in practice was a challenge. Most techniques for probing the resonator’s fluctuations risk destroying the delicately engineered quantum state. Schwab and company settled for an indirect approach whereby they deduced the fluctuations of the resonator’s two quadratures through a theoretical analysis of the circuit’s frequency output spectrum. The results, shown in figure 2, reveal that when the ratio of blue-detuned to red-detuned power is between 0.3 and 0.6, the quadrature with the lower noise (plotted in red) is squeezed below the zero-point level.

Figure 2. The resonator’s two quadratures have vastly different uncertainties (shown here in units of the zero-point uncertainty) when the coupled circuit is driven at red-detuned and blue-detuned frequencies simultaneously. As highlighted by the green box, the lower-noise quadrature (red circles) is squeezed below the zero-point level for some ratios of the blue-detuned and red-detuned power. Fluctuations of the higher-noise quadrature (purple squares) are much greater. (Adapted from ref.

The next goals include measuring the quadrature fluctuations more directly and squeezing the mechanical motion of larger objects. The Caltech researchers’ device, at 0.2 mm on a side, is big enough to see with the naked eye. It represents a step on the road to bringing quantum mechanics into the macroscopic world.

References

1. E. E. Wollman et al., Science 349, 952 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac5138

2. J. D. Teufel et al., Nature 475, 359 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10261

3. A. Kronwald, F. Marquardt, A. A. Clerk, Phys. Rev. A 88, 063833 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.88.063833

4. C. M. Caves et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 341 (1980); https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.52.341

V. B. Braginsky, Y. I. Vorontsov, K. S. Thorne, Science 209, 547 (1980).https://doi.org/10.1126/science.209.4456.547

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org