A new phase for the Fermi–Hubbard model

When quantum mechanical particles interact en masse, strange and mysterious things happen. The electrons in certain ceramics, for example, enter superconducting states at temperatures well above 100 K. Despite 30 years of study, the mechanism underlying that high-Tc superconductivity remains unknown.

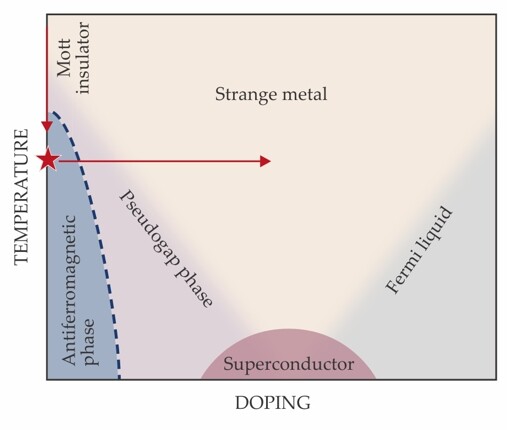

The Hubbard model is a stripped-down theoretical system that’s meant to capture the essential physics of exotic many-body phenomena. The model itself is simple to state: Quantum particles hop among the nodes of a discrete lattice, and they interact only with other particles on the same node. When the particles are spin-½ fermions, the Hubbard model is thought to have all the same phases as a high-Tc superconductor when the doping (essentially the difference between the number of particles and the number of nodes) and temperature are varied.

Although its Hamiltonian is easy to write down, the Fermi–Hubbard model is nearly impossible to solve, even numerically, for all but the simplest cases. So experimenters have taken to mimicking the model with a different physical system: ultracold atoms in an array of optical traps. Thus far, experiments have mostly been confined to the Mott insulating phase, in the upper left corner of the figure, far from the enticing superconducting phase.

Now Harvard University’s Markus Greiner

Cooling the lattice at zero doping brought it into a state of long-range antiferromagnetic order, marked by the red star in the figure. Doping the system at low temperature destroyed the order. Greiner and colleagues are eager to explore more of the phase diagram, but they point out that there’s rich physics to be found in the phases they can reach now. For example, by removing an atom from a particular lattice site and watching how the resulting hole moves around, they can study nonequilibrium dynamics in a way that’s otherwise inaccessible to either theory or experiment. (A. Mazurenko et al., Nature 545, 462, 2017

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org