A new approach to teaching physics

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2440

If you are a physics professor, you probably teach undergraduate courses that fulfill some kind of requirement, either for general education, for a major, for graduate school preparation, or for admission to professional training, such as medicine or engineering. Imagine, instead, that you were offered a chance to teach a physics course that didn’t fill any specific requirements, but had to be accessible to students with no previous physics training. What would you teach?

That’s the situation in which I found myself when I first came to Sarah Lawrence

To be clear, many of our students do go on to graduate or professional schools, so we still need to teach the usual courses in, for instance, general physics and quantum mechanics; but we’re also expected to teach what Sarah Lawrence calls “open courses"—that is, courses designed to appeal to students across the curriculum.

At first, that sounded easy to me. All I needed to do was stick “Physics of,” in front of a jazzy topic: Physics of Warfare, Physics of the Environment, Physics of Everyday Life, Physics of Weather, Physics in the Movies, Physics of the Human Body, and so on. But at Sarah Lawrence, faculty members quickly learn that such courses don’t work well.

When I thought of teaching Physics of Warfare (or Weather or . . . ), I soon realized that the temptation was to take topics from general physics such as force and energy, water them down to a level appropriate for a broad audience, and then apply them to examples chosen from the topic in the course title.

For Sarah Lawrence students, that approach would be unappealing. If they want to learn general physics, they take general physics, and are likely to scoff at a “light” version of the class. And if they want to pursue individual applications like warfare or weather, than they can do that through independent projects associated with our general physics courses, rather than through a separate five-credit class.

Designing an open physics course for Sarah Lawrence thus requires careful thought about subject matter, content, and pedagogy. Making that kind of effort yields ideas that I believe are useful for thinking about general education physics courses elsewhere as well. In this essay, I’ll describe three of the open courses I’ve developed for Sarah Lawrence.

Design principles

In designing the courses, I kept the following principles in mind:

- Open courses must appeal to students at all levels, from seniors ready for graduate school in physics to those who have never heard of Newton’s Laws. In order for that to be successful, each course must focus on material that’s orthogonal to the standard curriculum.

- The course topic should drive the choice of what physics to cover.

- Students should be able to bring a variety of skills to bear on the class, such as those related to history, art, philosophy, or communications. This way, every student will have a strong background for some aspects of the class and a weak background for others; this forestalls a hierarchy of well- and poorly-prepared students.

- Nonphysics elements of the class should be central to its purpose and design, and not seem like arbitrary or catchy additions.

- Fun and excitement should be byproducts of the learning experience, not adornments to it.

- For open courses, teaching students methodology is more important than teaching them content.

- To be effective, the methodologies being taught must be applied more than once in the course.

- When we offer more than one open course, each should be designed to develop different skills, so that students taking multiple courses don’t find them repetitive.

Rocket science

Rocket Science is, in essence, an open engineering course. Students learn to design, build, launch, and analyze their own rockets. They go through the entire cycle twice so that they can learn from the performance of their first design. The course also includes the history and future of spaceflight and culminates with groups of students developing and presenting plans for future space missions.

When students ask me what skills they need in order to take the course, I tell them that the three areas which they will find helpful are a background in physics, a facility with computers, and practical crafts techniques. Even talents like origami can come in handy! Because no one arrives on day one either completely accomplished or completely lacking in all three areas, all students will have strengths to build on and skills to develop.

The freedom to design their own rockets leads to remarkable designs. Some are flying works of art, featuring unusual symmetries and fine workmanship. Some include advanced features like multiple stages, clustered engines, or helicopter blades.

One of my favorite designs included a canopy through which a small toy soldier could be seen. When the rocket reached its apex, it “exploded” (actually a controlled separation), blowing out the canopy and ejecting the soldier, who then descended on his own parachute.

Of course, learning how to design rockets and space missions does entail learning something about forces and energies, but those topics are introduced in service to the goal of creating a successful vehicle. Even for students who have considerable previous work experience in physics, Newton’s second law remains fresh when it is introduced in the context of a moving object whose mass is changing.

Crazy ideas in physics

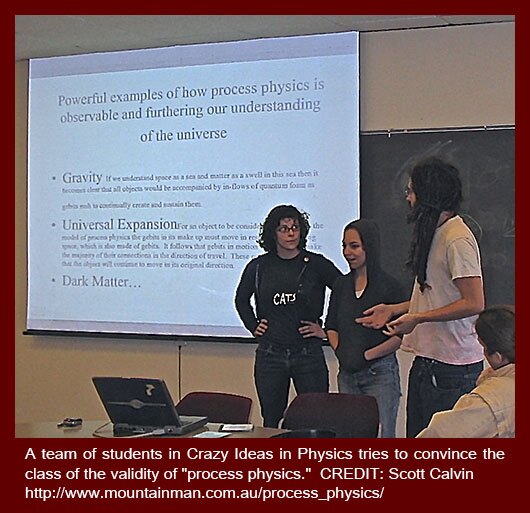

This course is about the process of theory evaluation: How do we decide whether a new theory is revolutionary or just plain nuts?

From the beginning of the course, I emphasize that the process is not easy. If we could tell the next Albert Einstein from the next Immanuel Velikovsky

The central activity of the course consists of ‘theory debates.” To begin, each pair of students chooses a theory from a list. Many of the theories will be unfamiliar to most students: strangelets, the Schwarzschild proton, and weak stability boundary theory, for example. Others have specific historical relevance, such as the Baghdad battery, the Antikythera mechanism, or the story of lost cosmonauts. Finally, a few are higher profile, but controversial: cold fusion, M-theory, and trutherism.

Once they have chosen a theory, each pair of students presents it to the class using the conventional methods of communications in physics: the poster, the PowerPoint presentation, and the peer-reviewed paper. The paper undergoes real peer review, both by students in the class and by students in other classes. Following review, the presenters revise their paper.

The process, from poster to final paper, takes several weeks. By the end, the theory has been pushed, prodded, and refined, just as in the “real world.” There is an important twist, however: Because we are trying to learn to distinguish science from pseudoscience, the students are permitted to fabricate data or misuse sources!

The rest of the class is assigned individual investigative tasks for each theory. One student will verify that references are used appropriately, another will consider whether the conclusions really follow from the evidence presented, a third will examine the backgrounds of the real-world advocates, and so on.

Tasks rotate for every theory under consideration, so that any individual student is at any given time involved in presenting one theory, checking sources on another, considering the internal consistency of a third, and so on. The arrangement gives each student a unique role with respect to each theory, so that each student’s work is integral to the success of the class as a whole.

Finally, we vote on each theory, ranking its plausibility on a scale of 0–4 (adapted from the scale Robert Ehrlich devised for his book, Nine Crazy Ideas in Science: A Few Might Even Be True) and the honesty of the presentation, also on a scale of 0–4. The presenters themselves finally reveal what they really thought and what skullduggery they may have committed, and productive discussion ensues.

Steampunk physics

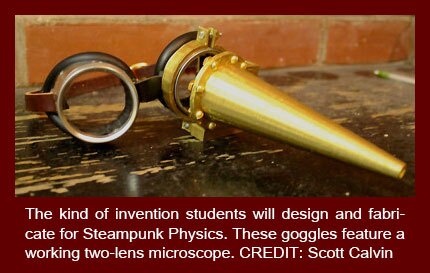

This is a new course, scheduled for the first time this fall.

Steampunk, for those unfamiliar with it, is a movement within literature, film, popular culture, technology, and fashion, which re-imagines the Victorian era with an emphasis on personal technology and individuality. The motto of Steampunk Magazine

Those devices are, as we know, tightly bound up with 19th-century developments in physics and technology.

In Steampunk Physics, therefore, the emphasis will be on learning 19th-century physics in its historical context, and then devising and constructing personal technology using those principles. In accord with the “Steampunk” part of the course title, the devices must have an aesthetic appeal. In accord with the “Physics” part, they must actually function!

The course will include four major units: optics (goggles), buoyancy (zeppelins, but also early submarines real and imagined, such as Jules Verne’s Nautilus), mechanical advantage (gears), and power sources (wind-up springs and early batteries). For each unit, we will learn about the physics directly from 19th-century sources rather than textbooks, and then each student will apply those principles to build a project of their own design.

Fashion and style are central to the steampunk movement, and so they will be part of the class as well. On presentation days, and on a few special days when we show our results to the campus community, students (and faculty!) must dress the part.

The dress-up requirement exemplifies how nonphysics elements can be essential to a course. Steampunk is not an afterthought, grafted on to an existing course. What kind of physics appears in the course is driven by the technology favored by steampunk. Magnetism, for instance, is not a big motif in steampunk, and thus will not be a central element of the class. History of physics enters naturally as well.

Final thoughts

The three courses may be “open,” but they are not easy. All of them depend vitally on the students’ contributions to be successful—which is what makes them uniquely rewarding to teach. Just as the students can build on a variety of pre-existing strengths, I am sure to learn from them. Whereas I am the most experienced physicist in the class, I am not the best artist, the most learned philosopher, or the most thoughtful fashion designer.

The lessons I have learned from designing and teaching these courses have application to general education courses at other institutions. As an example, “Physics for Poets” is a label that has been used, often disparagingly, for watered-down general physics aimed at a general population. But how much more interesting and valuable would it be, for instance, for such a course to live up to its name and focus on teaching students to write physics-themed poetry? Hmm . . . I may have just come up with my next course idea!

Scott Calvin