A metamaterial solves an integral equation

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4222

As computers’ processing speeds grow ever faster, they are approaching the limits of their electronic components. More speed requires additional power and smaller, denser chips, but miniaturization inhibits heat dissipation. Fiber-optic cables already transmit information encoded in light faster and more reliably than electrical cables can carry electronic signals. If computers also processed information as light instead of electronically, they could boost computational speed and mitigate the excess heat generation that besets electronic circuits as they become faster and smaller.

Switching from electrical to optical computing has other clear advantages. 1 In addition to faster signal propagation and less heat generation, optical signal processing is also inherently parallel. To understand why, consider imaging with a lens. The light intensity in the back focal plane is the spatial Fourier transform of the original signal. Performing the same Fourier transform electronically would require the function value at each point to be calculated sequentially, but with optics all points are evaluated simultaneously.

Researchers are developing materials and devices that may one day lead to practical optical computing technologies. Many of them manipulate light in the same way that switches and logic gates direct electronic signals. Those switches and gates would then be assembled into larger, multifunctional networks. But there’s no reason the strategies used in light-based computers have to mimic those of conventional computers, and other approaches target devices designed to perform specialized functions in ways that could surpass electronics.

Nader Engheta at the University of Pennsylvania and his collaborators have now built a device that solves integral equations using light. 2 Their metamaterial block repeatedly manipulates a microwave input signal until it reaches a steady state that represents the equation’s solution. Although the device is not yet reconfigurable or programmable, it is smaller than those using other optical processing schemes and has the potential to solve integral equations much faster than a conventional computer.

Designing a device

Engheta first proposed using metamaterials for electromagnetic signal processing 3 in 2014. He envisioned layered blocks whose varying permittivity and permeability would perform a mathematical operation on the incoming signal such as taking a derivative or integrating. Other groups have used different strategies to tackle optical signal processing, 4 but metastructures have the potential to form smaller devices and be incorporated into circuits. They also process signals nonlocally: The input signal scatters through the device and affects the output at every point in the function’s domain, which allows the metastructure to solve global problems like integrals.

The new device developed by Engheta’s group does more than perform a mathematical operation—it solves equations. The researchers focused their attention on equations of the form

Figure

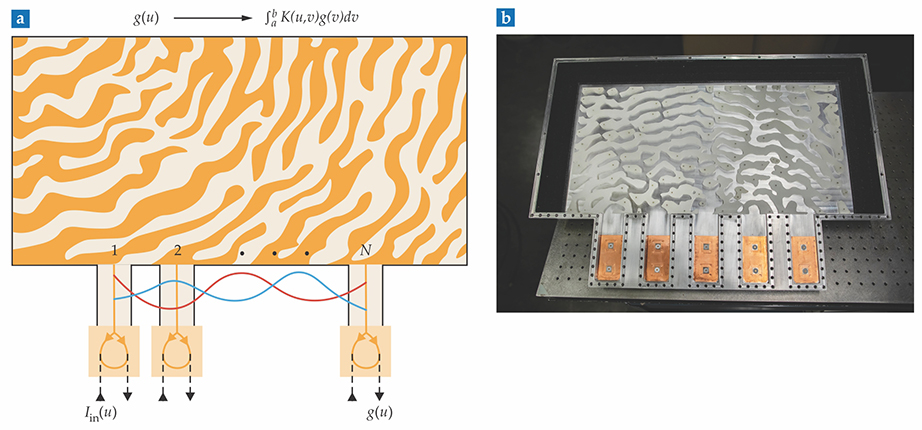

Figure 1.

A metastructure device integrates an incoming signal over a kernel

The instructions for evaluating an integral over a particular

After Engheta and colleagues confirmed through simulations that their strategy works, they built the device shown in figure

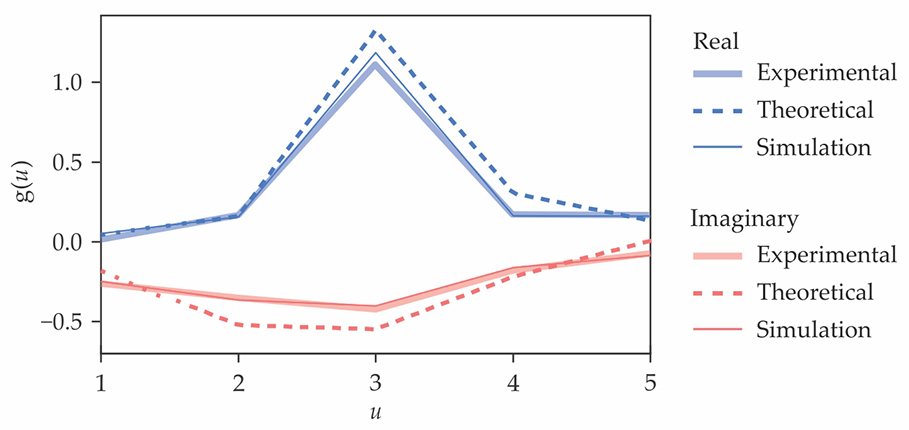

The researchers tested their device with an input signal at each of the five waveguides and measured the amplitude of the steady-state output. Their results, shown for the center waveguide in figure

Figure 2.

An input signal

For a simulation of an input signal propagating through the device, see the online version of this story.

Adaptations and reconfigurations

Optical computing has a long way to go before it challenges electronic computing. “One big advantage of current computers is that they’re programmable,” says Engheta. “The piece of computer that you have in front of you is one hardware but you can do many things with it.” To be programmable, the structures in an optical computer will have to be reconfigurable. The group is exploring phase-change disk technology used for rewritable CDs to make reconfigurable metastructures that can then serve as more than one kernel.

Computing with light could also relax the requirement that functions be discretized for numerical analysis. In their proof-of-concept device, the researchers did discretize their function by using a finite number of waveguides because it was a convenient way to control

The device that the researchers built was the size of a briefcase—about 30 cm by 60 cm—also for convenience, which meant that they had to use microwaves. It’s easier to engineer a device on that scale than on the microscale. And polystyrene, which is commonly used with microwaves, is readily available and inexpensive. Now that the researchers have demonstrated a proof of concept, they want to shrink the device so that it works in the near-IR. Features and even whole devices would then be on the micron scale and potentially suitable for chip-based technology.

Moving to the near-IR will also improve the device’s speed. The group’s analysis shows that it takes about 300 times the wave period for the device to converge on a solution. The microwave frequency in the group’s experiments is a few gigahertz, so it takes tens of nanoseconds to solve an equation. In the near-IR that time would be picoseconds—faster than current processors execute a single instruction.

Now that they’ve constructed a device that can solve one type of integral equation, Engheta’s group is working to widen its applicability. In addition to solving different forms of linear integral equations, they would also like to introduce nonlinearity and combine multiple swiss-cheese kernels to solve systems of coupled equations.

References

1. H. J. Caulfield, S. Dolev, Nat. Photonics 4, 261 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.94

2. N. M. Estakhri, B. Edwards, N. Engheta, Science 363, 1333 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2498

3. A. Silva et al., Science 343, 160 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242818

4. X. Lin et al., Science 361, 1004 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8084

T. Zhu et al., Nat. Commun. 8, 15391 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms153915. A.-M. Wazwaz, Linear and Nonlinear Integral Equations: Methods and Applications, Springer (2011).