A complex fluid exhibits unexpected heterogeneous flow

DOI: 10.1063/1.3463618

Flowing water, like other Newtonian fluids, is fully described by the Navier-Stokes equations. But many everyday materials, such as foams, emulsions, and colloids, are complex fluids that lack a description of similar generality. Faced with that gap, researchers instead look for similarities among different fluid systems to better classify their behavior. One such class, the yield stress fluids (YSFs), includes materials such as mayonnaise, hair gel, and toothpaste that hold their shape under low stress but flow under high stress.

Recently, YSFs were further classified into those that exhibit thixotropy—the decrease of viscosity with time during continued flow—and those that don’t. 1 Thixotropy in a YSF leads to heterogeneous flow such as shear banding: In response to a homogeneous shear stress, part of the material becomes liquid and flows more and more easily with time, while the rest remains solid. Shear banding is an important phenomenon to understand and control when handling YSFs industrially. Now, Sébastien Manneville, of the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, and colleagues have observed unexpected shear banding in a nonthixotropic, or “simple,” YSF. Unlike the thixotropic YSFs, which show shear banding in the steady state, the simple YSF’s shear banding was transient—but the transient regime lasted a surprisingly long time. 2

Stressed out

Complex fluids owe their complexity to structural elements, such as colloidal particles, that are much larger than small molecules but much smaller than the bulk. Thixotropy can arise in a complex fluid (which could be a YSF or not) when those structures attract each other to form aggregates that stiffen the material. When the fluid is forced to flow, the aggregates break down. As a result, more stress is required to initiate flow in a thixotropic YSF than to sustain it, and the fluids don’t always flow homogeneously, even when subjected to homogeneous stress.

But simple YSFs have no reason not to flow homogeneously. So Manneville and colleagues didn’t expect to see any shear banding. When they set out to study their material’s flow under shear stress, they were hoping to get some insight into how a YSF yields, or turns from solid to liquid. More specifically, they wanted to see whether the smoothness or roughness of the container walls had any effect.

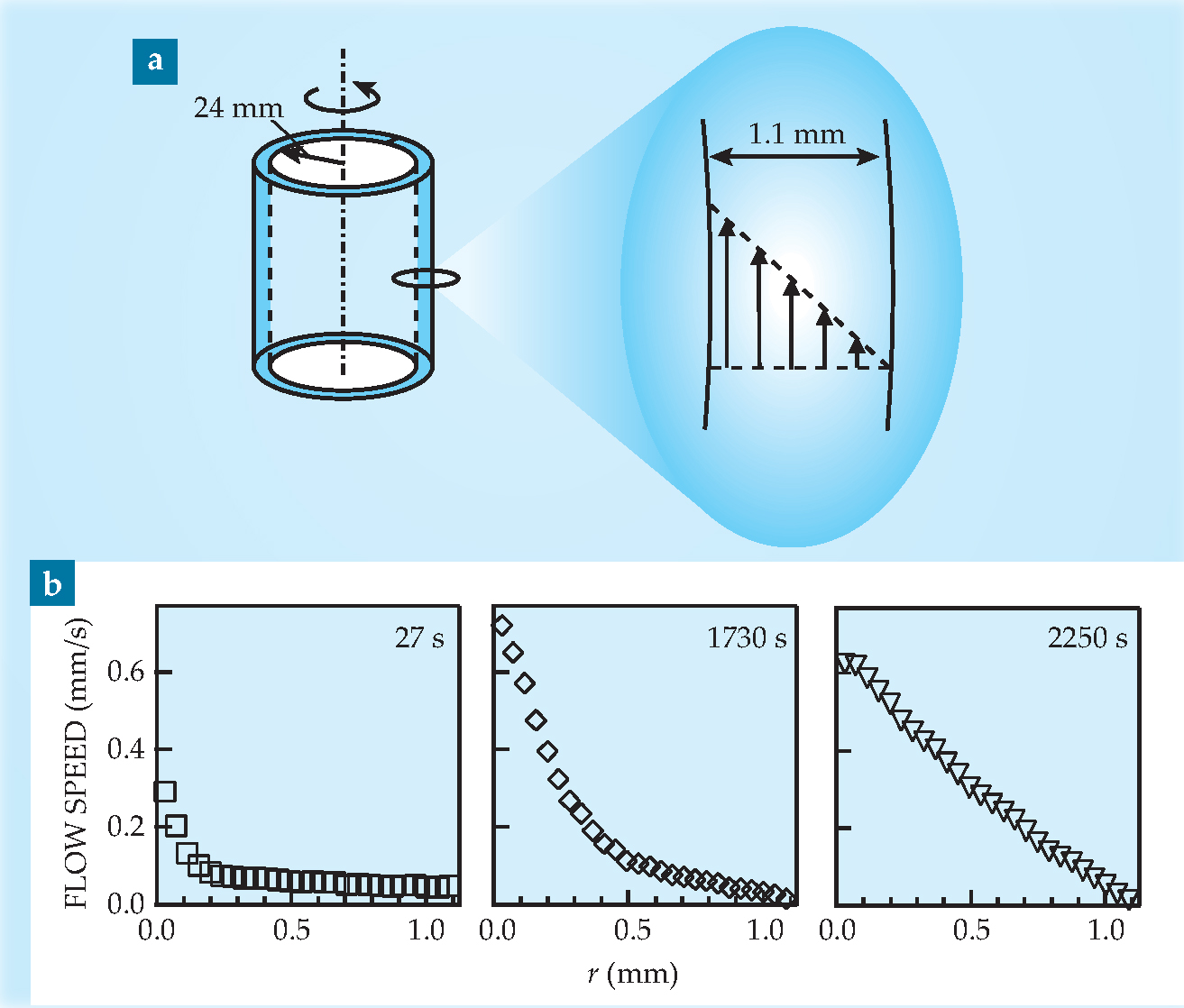

The material they studied was carbopol gel, a main ingredient in hair gel and many pharmaceutical gels. Synthesized from carbopol powder and water, the gel itself is an assembly of soft, swollen polymer blobs. The researchers used a rheometer equipped with a Couette cell, shown in figure 1(a): A layer of gel filled the 1.1-mm gap between two concentric cylinders, and the inner cylinder was rotated at a constant rate.

Figure 1. (a) Geometry of the Couette cell used in the experiment. Carbopol gel fills the gap between two concentric cylinders, and the inner cylinder rotates at a constant rate. The inset shows a velocity profile corresponding to homogeneous flow. (b) Three velocity profiles recorded for a shear rate of 0.7 s−1 (a rotational period of about three minutes). After 27 s, flow is mostly confined to a thin shear band around the inner cylinder; after 1730 s, the shear band is thicker; and after 2250 s, the flow is nearly homogeneous.

((a) Adapted from

To measure the gel’s velocity profile, the researchers used ultrasonic speckle velocimetry, a technique Manneville had developed for cheaply studying optically opaque fluids. 3 They seeded the gel with micron-sized glass spheres, which scatter acoustic waves, and aimed an ultrasonic transducer at the sample at an angle to the direction of flow. Every millisecond or so, they shot an ultrasound pulse through the gel and recorded its reflection. From correlations between consecutive shots, they deduced the gel’s velocity as a function of position and time.

Not so simple

Figure

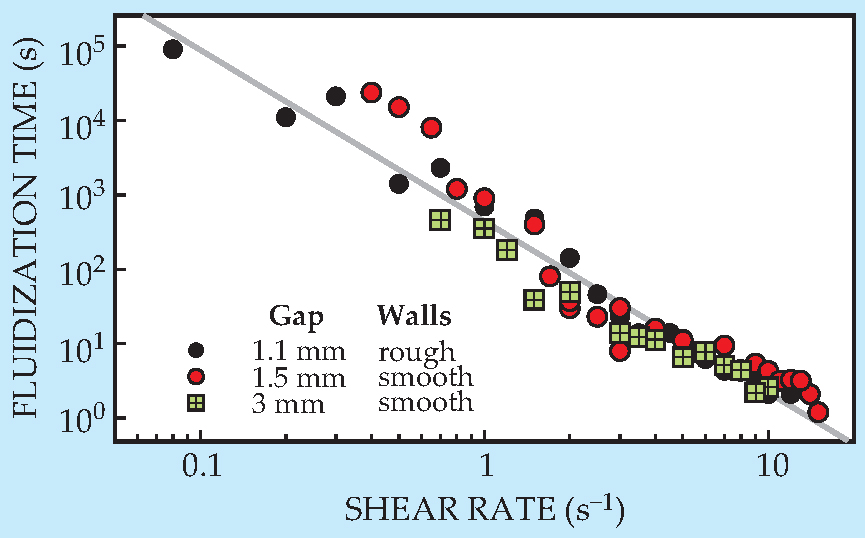

Manneville and colleagues repeated the experiment, rotating the cylinder at different speeds. Not surprisingly, fluidization happened faster when the cylinder was spun faster. But quantitatively, the dependence took an unexpected form: The fluidization time was inversely proportional to the cylinder’s speed raised to the 2.3 power. When the researchers looked at thicker layers of gel, they found a power-law dependence on the shear rate (the inner wall’s linear speed divided by the gap width), as shown in figure 2. And it mattered little whether the inner and outer walls were bare plexiglass or whether they were coated with sandpaper to make them rough.

Figure 2. Power-law dependence of the fluidization time (the duration of the transient shear banding) on the shear rate. Symbols represent different gap widths and different boundary conditions, as indicated by the legend. The gray line is a power-law fit with slope −2.3.

(Adapted from

Where the exponent 2.3 comes from is unclear. The researchers think it’s a material property, since using carbopol gel from a different batch—which may have had different-sized polymer blobs—was enough to change the exponent from 2.3 to about 3. They’re now looking at gels prepared with different concentrations of carbopol powder to better understand the material dependence. Extending the study to different simple YSFs, such as foams, would be more difficult: The high acoustic contrast between a foam’s gas and liquid phases makes the ultrasound probe unsuitable.

The observation of transient shear banding shows that nonthixotropic YSFs are not as simple as they’ve been assumed to be; they don’t yield uniformly, even under uniform stress. (The researchers briefly looked at other flow geometries to make sure that the shear banding was not an artifact of the slight stress heterogeneity induced by the circular geometry.) That the power-law relationship is independent of the layer thickness means that the fluid boundary doesn’t simply diffuse across the gel. And the long fluidization times point to the importance of distinguishing between steady-state and transient regimes in future YSF models and experiments.

References

1. D. Bonn, M. M. Denn, Science 324, 1401 (2009); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1174217

P. C. F. Møller, J. Mewis, D. Bonn, Soft Matter 2, 274 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1039/b517840a2. T. Divoux et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 208301 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.208301

3. S. Manneville, L. Bécu, A. Colin, Eur. Phys. J.: Appl. Phys. 28, 361 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjap:2004165

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org