A compelling mechanism for soot formation

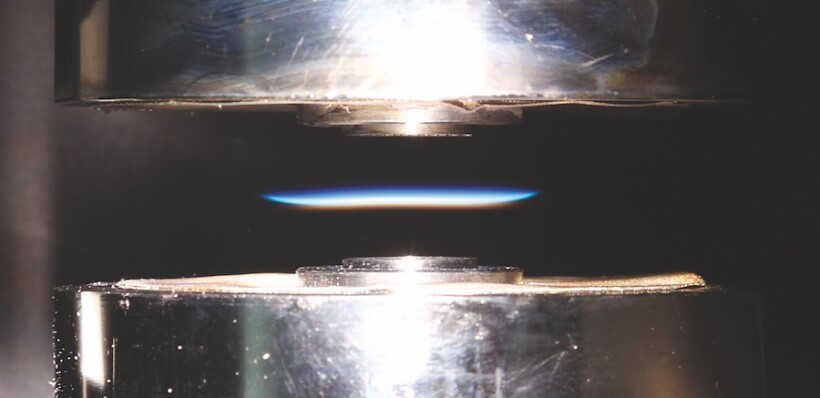

Photo courtesy of Hope Michelsen and Matthew Campbell

When diesel, kerosene, firewood, and other hydrocarbon fuels are burned, they produce carbon particles known as soot. Airborne soot absorbs solar energy and nucleates raindrops; it is also a pollutant that can lead to lung cancer and respiratory diseases. But how soot forms is a puzzle. Many common substances vaporize when heated and condense when cooled. In contrast, gaseous fuel molecules stick together when heated to produce solid soot particles. Researchers want to better understand the process that rapidly and durably links together soot’s precursor molecules, hydrocarbon rings. Now Hope Michelsen

Using electronic structure calculations, the researchers determined a sequence of chemical reactions that could act as seeds for growing clusters of hydrocarbons. The key was maintaining a large pool of radicals—molecules with unpaired electrons. The radicals gain stability through resonant intramolecular interactions. A resonance-stabilized radical could react with other available hydrocarbons to form a larger molecule, jettison a hydrogen atom to become a radical again, and then undergo another reaction to form a larger, even more stable molecule.

The team proposes that the plentiful supply of two-carbon-atom molecules created by combustion generates resonance-stabilized radicals of varying size. Any of those radicals can initiate rapid formation of a 1–5 nm precursor soot particle by repeatedly reacting with other hydrocarbons. Radicals on the particles’ surfaces react with other available hydrocarbons and develop into 10–50 nm soot particles. The researchers used aerosol mass spectrometry and ionization-energy measurements to verify that the predicted sequence of molecules forms in a flame like the one pictured above.

Now that the process by which gaseous fuel molecules form soot is less mysterious, researchers and engineers could look for ways to reduce or control soot emission from engines, forest fires, and industrial processes. What’s more, the same formation mechanism could explain how gas in interstellar space produces dust. (K. O. Johansson et al., Science 361, 997, 2018