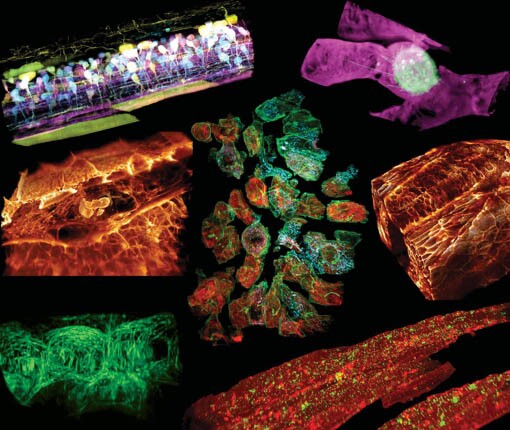

A cell’s life: The movie

A sampling of biological systems captured by the new imaging technique.

Tsung-Li Liu et al.

Cells and cellular organelles don’t operate in isolation or on glass microscope slides. Rather, they function in a complex environment that conditions what they do. Thus, to fully understand cellular and subcellular processes, a biologist needs to observe cells in their native habitat.

Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) is one promising and gentle approach for imaging in vivo (see the Quick Study by Abhishek Kumar, Daniel A. Colón-Ramos, and Hari Shroff, Physics Today, July 2015, page 58

The need for adaptive optics arises because the index of refraction in the complex cellular environment varies dramatically in space. As a result, wavefronts passing through the sample suffer an unknown distortion. In their approach to image correction, Betzig and colleagues induce points in the sample to fluoresce—that is, they create a cellular biologist’s version of the astronomer’s guide stars—and measure the distortion in their stars’ wavefronts. Armed with that information, they bounce the fluorescence light emitted by the entire sample off a mirror that is deformed to compensate for the average guide-star distortion. An independent, analogous procedure corrects for the aberrations created as the illuminating laser-light sheet passes through the sample. The result is an LSFM micrograph with greatly improved resolution.

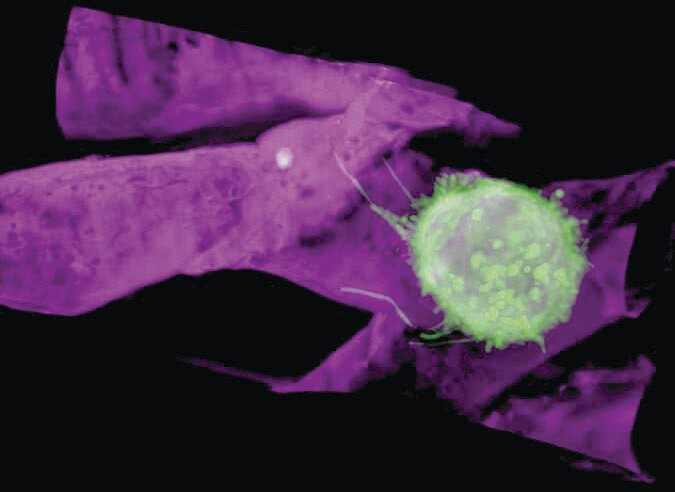

Tsung-Li Liu et al.

The movie, from which the figure above was extracted, indicates the quality of the combined imaging technique. The green sphere in the figure is a cancer cell, about 10 µm in diameter, that was implanted in a zebrafish. Note the thin tendrils that adhere to the zebrafish’s blood vessel (magenta) as the cancer cell rolls along the vessel wall. Other portions of the movie show the cell in a blockier shape, crawling along the wall and, creepiest of all, extruding material that allows it to cross through the vessel wall into the surrounding tissue. (T.-L. Liu et al., Science 360, eaaq1392, 2018

Movie 10 – Cancer cell migration in a zebrafish xenograft model