What it takes to be a presidential science adviser

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.3042

With President Obama’s science adviser John Holdren

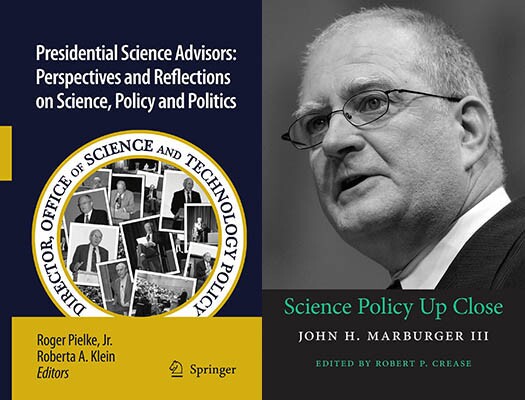

Two recent collections of speeches and essays by former science advisers provide food for thought to those interested in the past and future of White House science advice. In Presidential Science Advisors

Bringing science into the West Wing

The science adviser position has its roots in President Harry Truman’s creation of the Science Advisory Committee of the Office of Defense Mobilization. The director of the committee, which first convened in 1950, was considered the president’s unofficial source for science counsel. It took the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 to warrant the creation of an official science advisory position. Soon afterward, President Dwight Eisenhower created the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) and appointed MIT’s James Killian Jr to chair it as the first official presidential science adviser.

Since then, every president has appointed a science adviser—although there was a hiatus during Richard Nixon’s presidency. In 1973 Edward David Jr resigned in frustration, citing Nixon’s unwillingness to listen to his counsel. In response, Nixon dissolved the Science Advisory Committee and the adviser post, and declared that he would rely on NSF for advice instead. Gerald Ford quickly restored the position after Nixon’s resignation. In 1976, Congress declared that the presidential science adviser would also direct the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), which provides science guidance not only to the president but also to other federal government officials.

Presidential Science Advisors collects accounts from the seven scientists who counseled presidents on everything from lunar missions to the Human Genome Project. David recalls his successful effort to lobby Nixon not to cancel the Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 missions in 1972. Neal Lane, who served under Bill Clinton from 1998 to 2001, recounts debates over whether Francis Collins’s team at the National Institutes of Health should have been attempting to sequence the human genome when entrepreneur Craig Venter’s Celera Genomics was also on the case. In the end, said Lane, the rivalry calmed, and “President Clinton hosted an event in the East Room of the White House in which Collins and Venter shook hands and celebrated, together with the President, the completion of the first draft sequence of the human genome.”

For all the successes, many former advisers recall presidents considering and then rejecting their counsel. Lyndon Johnson’s science adviser Donald Hornig, previously a member of the PSAC during the Kennedy administration, recalls that the committee advised Kennedy not to pursue a Moon landing due to the extraordinary financial cost—advice Kennedy resoundingly rejected. Frank Press, Jimmy Carter’s adviser, recalls several instances when the president “told us [OSTP] that he agreed with our technical evaluation but would follow another course for political reasons—a reasonable action, it seems to us, for a President who has weighed all sides of a policy decision.”

Several past advisers also say that a personal relationship with and public loyalty to the president is an important component of the job. George Keyworth II built trust with Ronald Reagan by flying to California to speak with Reagan’s daughter Patti Davis, whose antinuclear activism was beginning to alarm the president. Lane argues that “the science advisor often speaks for the President on matters of science and technology. That means publicly supporting the President’s policies, regardless of whether he or she agrees with those policies.” Lane goes on to say, however, that the position “does not require sacrificing one’s integrity, e.g., making incorrect or misleading statements about science.”

Scientific advice and political controversy

John Marburger

The Boulder lecture series took place in the immediate aftermath of a rough period for then science adviser John Marburger. The former physicist came to the White House in 2001 with an impressive resumé that included leading Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University. Although the scientific community originally praised

Science Policy Up Close contains little in the way of personal reflection from Marburger on his experience. But two chapters’ worth of Marburger’s speeches during his tenure clearly indicate his desire to explain the Bush administration’s decisions to the scientific community. In a series of speeches to the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Forum on Science and Technology Policy, Marburger supported policies such as the American Competitiveness Initiative, which was implemented in 2007 with the goal of funding science in “the national interest.” After Bush left office, Marburger advocated more careful and rational study of science budgets and policy

Presidential science advisers have had to navigate the often-unfamiliar environment of Washington—and deal with political climates that are not always terribly favorable to scientific research. The nation’s next science adviser, and indeed all those in the future, should read about the experiences of previous office holders.