Column: When bad reporting happens to good science

inewsfoto/Shutterstock.com

Many of the research results we cover in Physics Today‘s Search & Discovery department also attract the notice of newspapers, websites, and other publications. I don’t usually pay them much attention. Physics Today‘s readership is different from that of most other news outlets, and our stories occupy a different niche in the science media landscape.

But a study I wrote about

The paper

Once you look past the headline, things get a little less dazzling, though no less important. The idea of harvesting water from the air has been around for ages. In a humid enough climate, it’s as simple as collecting the dew that condenses out of the cool night air. If the dew point is lower than the typical overnight low, humidity can still be harvested with the help of a desiccant, like those packets of “silica gel—do not eat” that get packaged with everything from jewelry boxes to vitamin pills. Desiccants can snatch water molecules from the air even when the relative humidity is less than 100%.

Compared with collecting dew, desiccant-based humidity harvesting has an extra step. The desiccant takes in water from the air, and then you have to get it out again. The drier the air, the harder that is. If a material has a strong enough affinity for water to pull molecules from the air when there aren’t many of them around, it’s unlikely to give them up easily.

Miller’s Diary

Physics Today editor Johanna Miller reflects on the latest Search & Discovery section of the magazine, the editorial process, and life in general.

That’s where Wang and Yaghi came in. Yaghi, a chemist, is a pioneer in the development of a new class of materials called metal–organic frameworks, or MOFs. Some of those MOFs, it turns out, have just the right properties to draw humidity from dry air and release it on demand. Wang, an engineer, focused on the design of the harvesting device, and in 2017 they published a proof-of-principle paper in Science.

Their paper’s abstract included the line “This device is capable of harvesting 2.8 liters of water per kilogram of MOF daily.” And that’s where the trouble started.

That statement expresses a ratio: liters of water per kilogram of MOF per day. It doesn’t say anything about how much MOF the researchers used, how many days they operated the device, or how much water they collected. But those subtleties were lost on almost everyone who reported on the work.

I’m sure it didn’t help that the press releases issued by the media relations offices at Berkeley and MIT both got it wrong. Berkeley, at least, had the sense to correct

News stories everywhere, from the Washington Post

In actual fact, the device—which, again, was a proof of principle, not even an attempt at a final product—used about two grams of MOF, ran for the equivalent of less than a day, and collected less than a milliliter of water. All those news stories had overstated the scale of the demonstration by a factor of more than 1000.

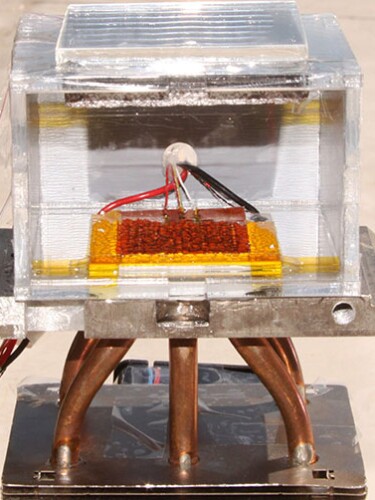

Even that might not have been so bad, except that most of the stories about the work (including mine) included a picture of the device, which is pretty obviously not a gadget capable of handling liters and liters of water. It doesn’t have a tap, spout, or any kind of storage vessel for the water, just a small surface where a few visible droplets condense. A reader who saw that photo alongside the outlandish claims in the text would likely think, whether consciously or not, “Hold on—this can’t be right.”

This water-harvesting device did not collect 2.8 liters of water over a 12-hour period.

Courtesy of Evelyn Wang/MIT

From conversations I’ve had over the years with nonscientist consumers of science news media, I’ve noticed that when they see a news story that seems wrong, garbled, or contrary to common sense, they’re often quick to conclude that the science must be wrong too. Some of them don’t fully realize that research papers, press releases, and news stories are different things written by different people. Others anchor their understanding so strongly to the news story—the first description of the work they’ve encountered—that they have trouble shifting their perspective even if they learn that the researchers are saying something different.

As a case in point, after my water-harvester story was published, a reader sent me a link to a video

(Thunderf00t also got really hung up on how, in the interest of expediency, the researchers used an electric cooler rather than a passive heat sink to keep part of their device at the temperature of the outside air, so their experiment slightly resembled a ludicrously small electric dehumidifier. Passive cooling—something Yaghi and colleagues eventually achieved in a follow-up study

What makes the debacle over Wang and Yaghi’s paper so frustrating is that it didn’t hinge on a highly technical theory that only a few people in the world can understand. It was about the meaning of a ratio and a commonsense understanding of the size of things. Any reporter who passed sixth-grade math would have been fully capable of understanding what the researchers did. Even if they based their reporting on the faulty press releases alone, they could have noticed the mismatch between the text and the photo and double-checked the numbers. It’s just that most of them didn’t. They saw a dazzling headline, and they ran with it.

Public trust in science is important—especially these days, with the twin crises of COVID-19 and climate change upon us—and it’s hanging on by just a thread. Regardless of the topics we report on, we science writers need to be mindful of our role in maintaining that trust. Because it’s not just our own reputation that’s at stake when we get it wrong.

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org