Column: Overconfidence and climate change

A couple of weeks ago, while I was looking for papers to write about for next month’s Search & Discovery department, I came across an advance press copy of a Nature Climate Change paper (now published

Miller’s Diary

Physics Today editor Johanna Miller reflects on the latest Search & Discovery section of the magazine, the editorial process, and life in general.

The paper starts from a really interesting premise: To make good decisions, the authors say, we should be accurate not only in our knowledge but also in our confidence about that knowledge. When we know a lot about a subject, we should be aware of our expertise, and when our understanding is fuzzy, we should realize that. That makes sense to me, and it’s apparently borne out by other research

If at this point you’re reminded of the Dunning–Kruger effect

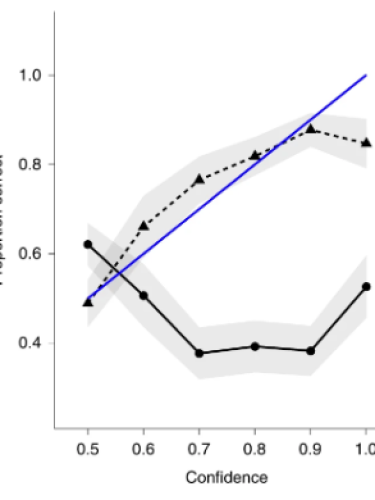

The Heidelberg researchers quizzed a few hundred members of the German public about eight statements on climate change. For each, they asked whether the statement is true or false, according to scientific understanding. Then they asked: How sure are you of that, on a scale from 50% (“I was guessing”) to 100% (“I know the answer”)? In a perfectly self-aware world, respondents who were 100% certain of their answers would be right 100% of the time, and the self-reported guessers would be right 50% of the time, with a straight-line relationship in between (the blue line in the figure).

Survey participants’ confidence roughly mirrored their accuracy in recognizing true statements about climate change (dashed black line). But their accuracy in identifying false statements (solid black line) was dragged down by two questions that most of the group answered incorrectly.

H. Fischer, D. Amelung, N. Said, Nat. Clim. Change, 2019

Reassuringly, the statement on which participants did the best (“The increase of greenhouse gases is mainly caused by human activities”) is also the one on which they were most confident: 84% of the survey group correctly identified the statement as true, and the group’s average confidence was 78%.

What really caught my eye, though, were the two statements on which respondents did the worst: “The global average temperature in the air has increased approximately 3.1 °C in the past 100 years” and “An increasing amount of greenhouse gases increases the risk of more UV radiation and therefore a larger risk of skin cancer.” Both statements are false: The temperature rise over the past century is in the neighborhood of 1 °C, not 3 °C, and the major greenhouse gases have essentially nothing to do with depletion of the UV-blocking ozone layer. But few of the participants—33% and 24%, respectively—correctly identified them as such. That’s considerably worse than the 50% you’d expect if everyone had guessed randomly. Moreover, the group’s confidence in those answers, at 71% and 75%, was still high.

What’s going on? The authors don’t say, and I can only speculate. But I’ll note that both of those statements (and none of the others on the quiz) make it sound like the climate-change situation is even worse than it is. If the German public has gotten the message that climate change is bad—and is thus inclined to agree with exaggerated claims of its badness—their simultaneous poor performance and overconfidence on those questions is understandable.

This kind of susceptibility to exaggeration can be harmful, especially on a nuanced subject like climate change for which seemingly contradictory statements are both true: It’s likely too late to avoid all of the worst of its effects, but the more swiftly and broadly we act, the greater our chances of escaping the worst of the worst. Without an accurate sense of perspective, you might be tempted to declare the whole thing hopeless, grab some popcorn (or, if you’re Jonathan Franzen

There’s a lot of information—and misinformation—out there, and keeping it all in perspective is hard. Even if you can distinguish the truth from the lies, the truth is a messy, complicated thing to keep straight in your head. The German survey participants overwhelmingly recognized that climate change is harmful and caused by human activity. But even they confidently claimed to know things that were completely wrong.

Although I don’t have all the answers, my Physics Today colleagues and I strive to do our part by creating a source of science news that you can trust. The research developments we choose to highlight in Search & Discovery, about climate change or anything else, are not always the most shocking or attention-grabbing results, but they’re ones that the experts assure us are worth knowing about. We take great care to make sure we cover them accurately and in the proper context, and if the research’s conclusions are uncertain in the scientific sense of the word, we’ll tell you. When you read one of our stories, I hope you can feel confident in what you’ve learned.

Thumbnail photo credit: Chris & Karen Highland

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org