Climate geoengineering reenters media spotlight

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.8214

The stratosphere is the whitish layer in this 2010 photo of space shuttle Endeavour.

NASA

Harvard’s solar geoengineering researchers exercise caution when discussing their planned, comparatively tiny-scale aerial experiment. They seek knowledge applicable to what in a 2015 report

The NRC cites inducements to caution:

It is far easier to modify Earth’s albedo than to determine whether it should be done or what the consequences might be of such an action. One serious concern is that such an action could be unilaterally undertaken by a small nation or smaller entity for its own benefit without international sanction and regardless of international consequences.

It’s not always clearly recognized that Harvard’s prospective experiment wouldn’t remotely reengineer the atmosphere. Experimenters propose only to send a balloon about 20 km up, two researchers wrote in the Guardian on 29 March, with the objective

It is not a “test” of planetary cooling. The amount of material we would release is tiny compared to everyday activities. For example, if we tested sulphates, we would put less material into the stratosphere than a typical commercial aircraft does in one minute of flight. Our material of choice for the first flight? Frozen water. Later flights might include tiny amounts of calcium carbonate or indeed sulphates.

Keith and Wagner were reacting to what they called bias and distortion in the 27 March Guardian article

Merely reckless? That got taken much further at the UK’s Daily Mail, a publication closely linked to the Mail on Sunday, which in February falsely alleged

Climate manipulation and Trump

Other publications have emphasized geoengineering worries without conflating a proposed modest experiment and a conjectured planet-scale project. The Independent headlined an article

Not much in the media addresses why the Trump administration would fight something it believes doesn’t exist. But the New York Times in December examined

Consider the opening of a 6 April article

While President Trump floors the accelerator for global warming through executive orders and appointments of notorious climate deniers to his administration, members of his inner circle are touting “climate engineering” as a cheap way to insure the planet against harm without any need to change lifestyles or curb the oil and coal industries. They resemble compulsive eaters who count on frequent liposuction rather than maintaining strict diets to keep their body fat in check and stay healthy.

Many reputable scientists are calling for more research on what some call “Plan B": planetary-wide interventions to engineer a way to avoid global climate disruption if measures to reduce carbon emissions fall short. But they approach such solutions with extreme caution, and critics warn that such a cure may be as bad as the disease.

At the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a report

Harsh realities

That wariness has been around for decades, as physicist and historian Spencer Weart

Keith and Wagner stipulate that the wariness is “healthy” and that it would be “reckless” to conduct geoengineering without further research. But they also cite authoritative support for further study: not only from the NRC, but from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Royal Society

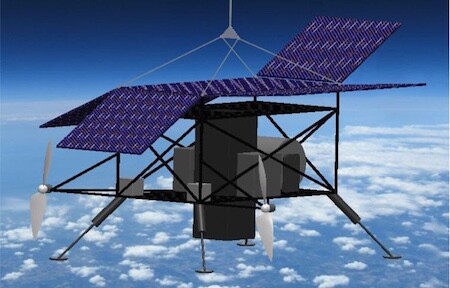

A concept of the vehicle that will deliver the payload for a Harvard team’s geoengineering experiment.

J. A. Dykema et al., Phil. Trans. Royal Society A 2014, CC BY 4.0

Keith and three colleagues contributed a 2014 paper

Laboratory systems, for example, are limited in their ability to realize gas flows that do not interact with the chamber walls, and interactions with the walls interfere both with chemical kinetics and with the dynamics of particles. Nor can laboratory experiments quantitatively simulate the catalytic role of UV photons on gas- and liquid-phase constituents with the correct solar spectrum and a realistic population of reactive intermediates.

Later they called it “plausible that conclusions reached with direct, in situ observations within the lower stratosphere itself will greatly simplify the scientific arguments.” They predicted “a better basis for public discussion and policy-making about the risks of SRM” than could be established by computer models and laboratory experiments alone.

The Harvard researchers found themselves and their envisioned experiment in the news following the Forum on US Solar Geoengineering Research

We need a diverse, systematic effort to figure out how solar geoengineering might work. That effort should be noncommercial, open access, and it must be international. Moreover, this is a problem where a multidisciplinary approach is absolutely vital. We need engineering and science, but unless it’s embedded in a larger universe that thinks about governance, thinks about business, thinks about ethics and even the way this fits in our environmental literature, we won’t be able to do something that really helps the world ultimately make decisions about it. We need a research program that thinks about how to reduce the technical risks by figuring out better science and technology and how to build institutions that have a better chance of governing a technology like this in a divided world.

It’s sometimes said that the climate wars offer much for students of agnotology

Steven T. Corneliussen is Physics Today‘s media analyst. He has published op-eds in the Washington Post and other newspapers, has written for NASA’s history program, and was a science writer at a particle-accelerator laboratory.