A horoscope for a physicist

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.2061

The author (right) poses with his father and 5-year-old daughter in Aachen, Germany, in 1975.

Lalit Sehgal

In the summer of 1957, I decided to pursue a master’s degree at the physics honors school of Panjab University in India. The town of Hoshiarpur, where my father was posted for his government job, happened to be the place where the physics department was located. The excitement surrounding the launch of Sputnik 1 a few months later affirmed my decision.

My father, too, had obtained a master’s degree from Panjab (in economics) in the late 1930s, when India was still under British rule and the university was situated in Lahore. He was later appointed as a statistical officer by the Panjab government.

But fate had not been kind to him. The violence accompanying the division of the country in 1947 forced him and his young family to flee from Lahore, leaving behind our home and belongings. In the travail involved in resettlement, my 6-year-old sister died of fever, in a place with few medical facilities. The trauma of the loss of our home, followed by the loss of a child, had a lasting effect on my parents. While continuing in his government job, my father turned to meditation as a way of maintaining his equanimity. He also developed an idiosyncrasy: In times of worry and uncertainty, he would consult an astrologer.

When I told him I had decided to study physics, he approved wholeheartedly. “Science has done wonders,” he said. I explained to him that after my master’s degree I would probably enter an academic career, which meant that my income, judging by the salaries of the time, would be modest. I also told him that given a chance I would like to go abroad for higher studies. All of this he accepted without demur, adding that, in his own experience, people in the scientific profession had integrity and were of high intellectual caliber. The conversation about going abroad, however, awakened in my father a new worry that made it urgent for him to see an astrologer: I did not yet have a horoscope.

Prophesies over tea

A few days after our talk, my father came home from work with some strange news: Instead of going to an astrologer, an astrologer had come to him. A man had visited his office with a request for two bags of cement, which he said he needed to carry out repairs in a temple where he was a priest. In those days cement was a restricted commodity that could be obtained only by applying to the office that was in my father’s charge.

During the discussion, my father asked the man if he knew how to make a horoscope. The priest replied that the temple he came from had in its possession a large number of ancient horoscopes that were originally written by a sage named Bhrigu. If the priest could have the particulars of the person whose horoscope was required, he would look into the pile of documents to see if the appropriate one was there. Intrigued, my father gave the man my name and place and date of birth and invited the priest to come to our home the next day for tea. I was more than a little embarrassed when I heard this, and also irritated that my father had dragged me into what appeared to be some sort of trickery.

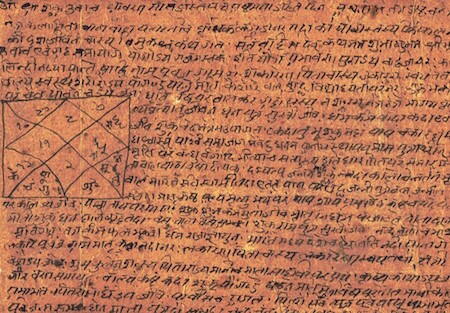

The next afternoon the man came to our home at the appointed time. We had tea, and then the man produced from his bag a brittle document made from thin parchment-like paper. It had on it a diagram, familiar from horoscopes I had seen, supposedly indicating the location of the planets, Sun, and Moon at the time of my birth. The rest of the document was filled with faded writing that I could recognize as Hindi or Sanskrit. The priest proceeded to read and give his interpretation of the writing. The first part of the horoscope seemed to dwell on the ancestry of the subject and his previous life. This was followed by a prognosis of the present life and the life thereafter. Certain things the priest said seemed plausible, but the rest was conjecture.

A portion of the author’s horoscope.

Lalit Sehgal

I sat there uneasily, barely able to conceal my skepticism, and took no part in the conversation. My father asked the man if he could send us a summary of what the horoscope said, written in ordinary, legible Hindi. He promised to do so, and I know he kept his word, though I have long since lost track of that paper.

At the end of the meeting, the priest said we could keep the document, since the temple had so many more. My father placed the horoscope in a box where it joined company with other horoscopes and important family documents. He now had the mental satisfaction that the horoscope of his eldest son was available, if and when required. I, on my part, was relieved that this meeting was over and that I could carry on with my plans to become a physicist.

In 1971, having completed a PhD program in the US and a postdoctoral stint in India, I was poised to travel to Germany for a new postdoctoral appointment. Before departing from Bombay I visited my parents’ home in Delhi. A cupboard in which books and papers were kept had been ravaged by termites. The wooden frame had been eaten up and the papers inside had been reduced to dust. A box of photographic slides I had brought back from the US had been turned into a powdered heap. Fearing that perhaps the horoscope had also been destroyed, I looked in the metal box. The horoscope was intact. I decided to take it along to Germany, where, at least, it would be safe from termites.

Revisiting the horoscope

It’s now 46 years since I brought the horoscope to Germany, and six decades since the priest from the Bhrigu temple gave it to me. It is lying unscathed in a drawer, folded in cellophane. I can read a few stray words, but it would require someone more conversant with horoscopes to be able to interpret it. In all these years, I have had no particular urge to have it read. But now, with time on my hands, I have become curious about its contents.

I looked on the internet and found a considerable amount of information and commentary on the subject. Bhrigu is celebrated in ancient scriptures as an expert in writing horoscopes. He had compiled the life histories of a large number of human beings and tried to correlate the histories with astrological (natal) data. In this way he had constructed what we would now call a phenomenological model for preparing the horoscope of individuals based on the parameters of their birth.

Bhrigu and his followers produced hundreds of thousands of horoscopes, and the knowledge needed to produce them was passed from one generation to the next by scholars who also belonged to the community of temple priests. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the country was invaded by foreign armies, who indulged in plunder and pillage. The local temples were a particular target. Large parts of Bhrigu’s manuscript were destroyed, and the priests who had custody of the collection dispersed to different parts of the country, taking with them whatever documents they could salvage. These groups reestablished themselves in several places, one of which was the town of Hoshiarpur, where I attended Panjab University physics classes.

Today, these places are centers that preserve the tradition of Bhrigu. Believers in the tradition come on pilgrimage, with the hope of finding a horoscope that fits their particulars. The production and sale of horoscopes has become a commercial enterprise, the different centers laying claim to possessing the largest part of Bhrigu’s original manuscript. Those with faith in astrology speak with awe of the accuracy of the predictions; skeptics denounce the whole activity as a money-making fraud.

Falsifying the unfalsifiable

Recently I happened to meet an acquaintance who is a respected philosopher and theologian with considerable knowledge of Indian scriptures. I told him I possessed a horoscope associated with Bhrigu and was looking for someone who could read it. His first reaction was one of surprise: He did not think that a scientist like me would be interested in horoscopes. I convinced him that my attitude to astrology remained skeptical, but I was curious to know what the horoscope said about my life; at my advanced age I would be in a position to falsify its prognostications.

My friend reacted to the word “falsify” with some distaste. A horoscope, he said, is not a scientific theory that can be proved or disproved. It stems from a philosophy of life that goes back to the earliest human speculation. At the very least, he said, one must accept the idea of birth and rebirth, and the belief that the progress of one’s life is determined by one’s karma, the cumulative sum of the good and bad deeds in previous births.

It began to appear that Bhrigu’s system had evolved into a kind of Theory of Everyone, applicable to every human being and embracing both their present and future lives. A horoscope provides a forecast based not only on natal data, but also on some estimate of karma. It also suggests ways in which subjects can improve their prospects by appropriate acts of charity and atonement. It is an ambitious theory, but the indefinable role of a person’s karma ensures that it is also unfalsifiable. In this respect, the Theory of Everyone has some similarity to certain modern-day Theories of Everything that also have so many imponderables as to render them unfalsifiable.

My scientific temper does not allow me to embrace an idea that is unfalsifiable. I have therefore no further desire to delve into the contents of my horoscope. But I do not wish to be too judgmental. The priest who came to my father’s office had merely requested some cement for the upkeep of his temple. The document he gave me was a gift. He wanted nothing in return. And in response to my father’s remark that I was a scientist who did not believe in astrology, he had said: “Please do not worry. Your son will find his own path to the truth.” I thought that was a gracious remark, and I wish I could have said something gracious in return.

Now, in the evening of life, the future that was foretold in my horoscope is largely in the past. I have some satisfaction that by bringing the horoscope to Germany, I may have saved it from the ignominy of being ingested by an army of termites. I shall endeavor to ensure that it will not be subjected to the mayhem of a shredding machine. I have saved a scanned copy of the horoscope on my computer. Perhaps a future scholar, wiser than myself, will someday study the horoscope and judge to what extent my life confirmed the prognosis spelled out in that document, brought to me by the priest of the Bhrigu temple of Hoshiarpur.

Lalit Sehgal is a retired nuclear and particle physicist. He lives in Aachen, Germany.