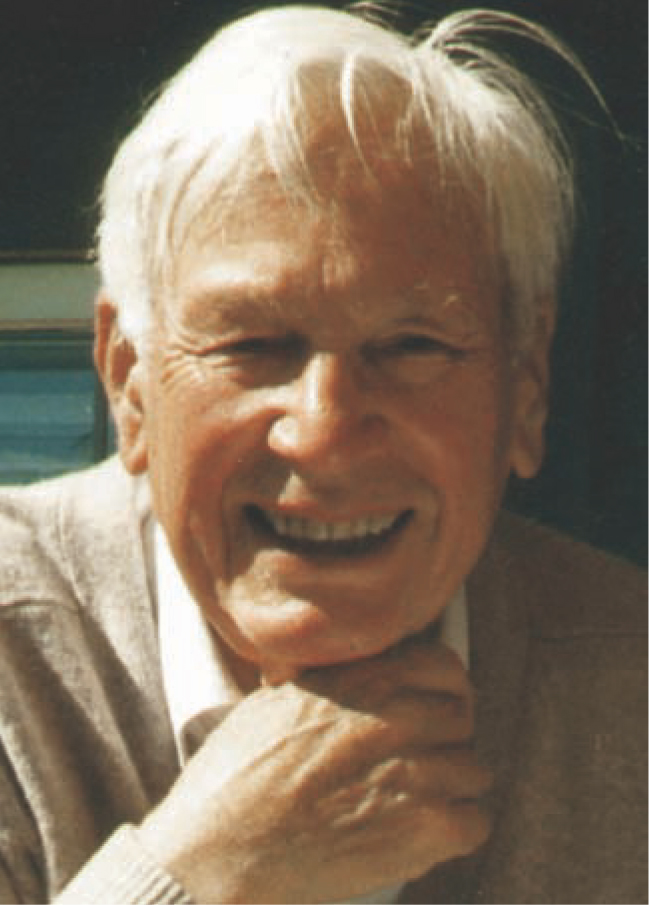

Maurice Henry Lecorney Pryce

DOI: 10.1063/1.1768681

Maurice Henry Lecorney Pryce was one of the most talented and versatile theoretical physicists of his generation. He died on 24 July 2003 in Vancouver, Canada.

Maurice was born in Croydon, England, on 24 January 1914. At the University of Cambridge, he gained a first-class degree in mathematics and started research in 1933 with Ralph Fowler and Nobel Prize winner Max Born. Two years later, he was awarded a prestigious Commonwealth Fund Fellowship to attend Princeton University, where he gained a PhD in 1937. His thesis was on the wave mechanics of the proton.

On his return to Cambridge in 1937, he was elected a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and his work on the then popular but erroneous neutrino theory of light came to the attention of Paul Dirac, who persuaded him to publish it. Maurice considered that to be the high point of his career.

During World War II, he worked on the development of microwave radar and subsequently on aspects of fission research, although he declined for moral reasons to be engaged directly in the development of the nuclear bomb. In 1945, Maurice returned to his fellowship at Trinity College and, during the next year, accepted the Wykeham Chair of Physics at Oxford University as a specialist in theoretical physics in the Clarendon Laboratory. There, a significant reputation in the low-temperature field had been established before the war, and work in the new field of electron spin resonance was just starting. Both topics were highly appealing to doctoral students, and Maurice, with his background in quantum mechanics and electromagnetism, was the ideal collaborator.

Soon Oxford was attracting potential theoreticians as doctoral students, who later moved to elsewhere in the world; among those were John Ward and Anatole Abragam. The laboratory was under the control of the autocratic head of the physics department, Frederick Lindemann (Lord Cherwell), whose ideas on building up a permanent staff did not always coincide with Maurice’s. The result was a sad one for Oxford: In 1954, Maurice filled the vacancy left at Bristol University in England, when Nevill Mott moved from there to Cambridge, and theoretical physics at Oxford suffered as a result.

At Bristol, Maurice became head of the physics department and continued to publish in a wide range of fields. After 10 years, he was attracted by, and accepted, an offer from the University of Southern California as distinguished professor of physics and chairman of the physics department. At USC, he became disappointed in the progress he could make in expanding the department and was frustrated with the associated politics, so in 1968 he moved to Canada to take the position of senior professor at the University of British Columbia. For the first time in many years, Maurice was totally free of administrative duties.

His most important contribution at UBC was as a helpful critic or collaborator on any problem in any branch of physics. His personal research included electromagnetic properties of pulsars, the quantum mechanics of the hydrogen atom in very large magnetic fields, and many problems in general relativity. Although much of his work was completed, virtually none was published. He had a substantial interest in experimental molecular spectroscopy and multiphoton processes. Maurice would always ask, “What is the experiment?” He wanted to know exactly what was being measured and how. But learning of a well-resolved complex UV spectrum of the hydroxyl molecule that had baffled professionals, he asked to see the data, fully expecting to finish his analysis over a weekend. After 25 years, much work, and many interesting collateral results, this spectrum remained for him a puzzle, and is still unsolved.

Maurice remained active in research and consultation, which included the problem of the disposal of radioactive waste, until 1999, when he suffered a stroke that left him effectively a quadriplegic at age 86. After a brief period of severe depression, his acceptance of his condition led to an active intellectual life, which continued until his death.

Maurice Henry Lecorney Pryce

More about the authors

Bill Dalby, 1 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada .

John Sanders, 2 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK .

Kenneth Stevens, 3 University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK .