Endel Lippmaa

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010327

Before I get to my subject, the late Endel Lippmaa, I digress to introduce the field in which he made his mark: solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). My first encounter with the application of NMR spectroscopy to solid samples came 15 years ago. For Physics Today‘s September 2000 issue I wrote a news story entitled “Solid-state NMR reveals key structural features of membrane transport proteins

Membrane proteins defy easy crystallization because their surfaces are both hydrophilic and hydrophobic. With x-ray crystallography unavailable for all but a handful of membrane proteins, biologists could, in principle, turn to the second-most productive method for determining the structure of biomolecules: NMR spectroscopy.

An NMR spectrum consists of resonance peaks whose properties are shaped by the chemical environment of each spin-endowed nucleus in the sample. The sensitivity to chemical environment arises because both the electrons that swarm around the nucleus and any neighboring spin-endowed nuclei alter nuclear magnetic moments in a predictable way.

Some of those spectral alternations depend on the orientation of the chemical bonds to the powerful magnetic field used in an NMR experiment. In a noncrystalline sample, the bonds of the constituent molecules are randomly oriented. That’s a potential problem for NMR spectroscopy because each different orientation has a slightly different resonance frequency. An otherwise sharp line can therefore be broadened—in some cases, so much that it overlaps with neighboring lines.

Broadening can be circumvented by putting the molecules in a liquid medium. The Brownian tumbling of dissolved molecules effectively cancels the directional dependence through geometrical averaging. Sharp resonance peaks result. But the cancellation fails for membrane proteins and other large molecules, which are too lumbering to sample all orientations on the nanosecond time scales of nuclear interactions.

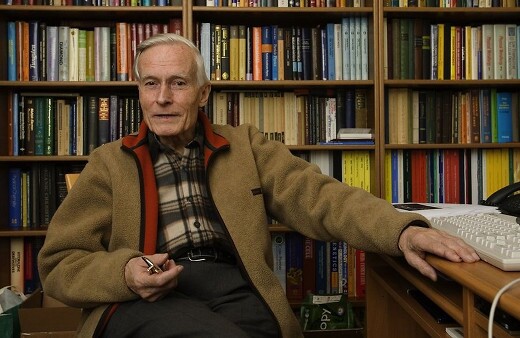

Endel Lippmaa (1930–2015).

CREDIT: Eesti Ekspress/Ingmar Muusikus

Devising ways to obtain sharp peaks in solid-state NMR was one of the abiding research interests of Endel Lippmaa, who died on 30 July at the age of 84. In 1978 Lippmaa and his collaborators invented pulse sequences that could recover information about bond orientations even when a technique, magic-angle spinning

Lippmaa’s most cited paper, “Structural studies of silicates by solid-state high-resolution silicon-29 NMR,” demonstrated in 1980 that high-resolution NMR spectroscopy could be applied profitably to inorganic samples, not just organic or biological ones. According to Google Scholar, the paper has garnered 969 citations.

Just one English-language newspaper, Britain’s Telegraph, marked Lippmaa’s death with an obituary

Before I get to Lippmaa’s archival investigations, I will provide some historical context. In the wake of Germany’s defeat in World War I, Soviet Russia sought to reassert by military force the Russian Empire’s century-long hegemony over the Baltic states. It failed. By 1920 Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania had each won their independence.

Nazi Germany’s annexations of Austria in March 1938 and of Czechoslovakia’s German-majority border regions in September 1938 revived Russian interest in the Baltic states and in the other countries that lie between Germany and the Soviet Union. Worried about the German threat from the west, Joseph Stalin sought a defensive alliance with Britain and France. But Stalin wanted more than allies. As a part of the proposed treaty, he demanded that Soviet forces be allowed free passage through Poland and Romania to meet any German threat. Britain and France refused to comply.

Rebuffed, Stalin changed tactics. To neutralize the German threat he sought an alliance with Adolf Hitler. Named after the Soviet and Nazi foreign ministers, the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact of 23 August 1939 was ostensibly a non-aggression treaty. However, secret protocols divided Eastern Europe between the two powers. In the north, Finland, Estonia, and Latvia were assigned to the Soviets. Poland was to be split and shared. Lithuania was assigned to the Nazis.

This photograph of a wintery landscape in Estonia echoes the colors of the country’s national flag. Flying the flag was illegal under the Soviet occupation.

CREDIT: Valmar Valdmann

The secret protocols came into effect following the invasions of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939. The Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states in June 1940. A month later, after rigged elections, communist puppets were installed to reign over Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Aside from the Nazi occupation of 1941–44, the Baltic states remained Soviet vassals for half a century.

Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 nullified the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, but its secret protocols continued to play a role long after the war. Even though photocopies of the pact and its protocols came to light in 1945, the Soviet Union could claim, in the absence of certified originals, that the copies were Western forgeries. The puppet regimes in the Baltic states were therefore legitimate.

As a distinguished and trusted scientist, Lippmaa was allowed in the 1980s to travel to the West. He used that opportunity to visit German and US archives. Eventually, as the Telegraph obituary writer puts it, he succeeded in turning up “hitherto neglected documents, annotated by Stalin and Ribbentrop, in Russian and German respectively, in which the two men exchanged views not only about taking over Europe but on how it should be done.” The obituary continues:

The production in public of copies authenticated by a US government stamp helped to undermine Soviet denials that the documents existed. It was Lippmaa’s production of the damning documents in 1989 that led to a sea change in the Soviet Union. In 1989 Lippmaa was among deputies of the three Baltic republics who challenged Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev at the Congress of People’s Deputies in Moscow, to produce the Soviet Secret Protocol. Gorbachev insisted that no such document existed, though he subsequently established a commission to investigate.

In December 1989 the commission concluded that the protocols were genuine; that they were in conflict with peace treaties concluded with the governments of the independent Baltic states in the 1920s and 1930s and that since they were enacted by the threat of force they should be declared null and void. The Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union subsequently passed a declaration confirming the existence of the protocols and denouncing them. The Soviet copy of the original document was declassified in 1992 and published in a scientific journal in early 1993.

The decision of the USSR Congress paved the way for the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to reclaim their independence and hastened the unravelling of the Soviet Union. Estonian Independence was declared on August 20 1991. It was recognised by the Soviet Union on September 6 and the country gained admission to the UN 10 days later. The last Russian troops left Estonia in 1994.

For more about Lippmaa’s life and achievements, see the obituary