The future of astronomy in Hawaii hinges on the Thirty Meter Telescope

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3230

Mauna Kea, on Hawaii’s Big Island, remains the favored site for the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), but in the face of multiple hurdles, the project’s leaders are making backup plans. The TMT partners hope the legal difficulties ensuing from the opposition to the telescope by some native Hawaiians will be resolved by early next year. If not, though, the partners intend to start construction somewhere else in April 2018.

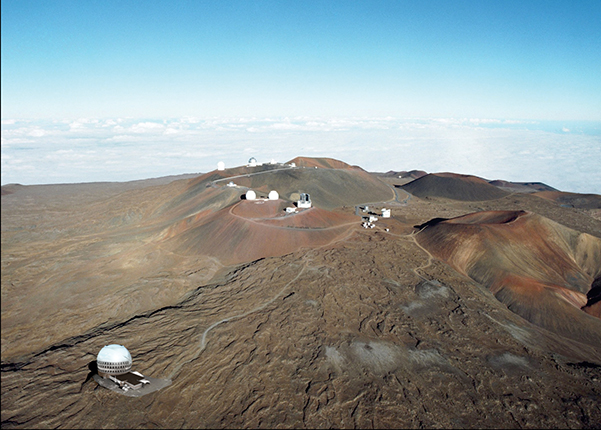

Uncertainty clouds the future of astronomy on Mauna Kea as opponents protest the building of the Thirty Meter Telescope there. An artist’s rendering shows what the mountain would look like with the TMT (left foreground).

TMT

In preparing a plan B, the TMT partners are evaluating sites in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. A change in site for the $1.4 billion next-generation telescope would have ripple effects for the global astronomy community. For Hawaii, in particular, “it will make it hard to convince future investors to put money into astronomy instruments and telescopes,” says Doug Simons, executive director of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, one of 13 telescopes already on Mauna Kea.

Procedural problems

When the TMT team selected Mauna Kea in 2009, it knew that some native Hawaiians see construction on the summit as a desecration of a sacred mountain. Indeed, opposition had previously dashed plans to build four 1.8-meter “outrigger” telescopes around the twin Keck telescopes. If the project had gone through, the six telescopes would have formed the world’s most powerful optical–IR interferometer.

Given that history, TMT project members made unprecedented efforts to take into account cultural and environmental issues and to forge good relations with native Hawaiians. That included getting their help in selecting the specific site for the TMT and offering them financial, educational, and job benefits.

So when protestors blocked construction in April 2015, their determination and numbers—estimates range from dozens to hundreds—blindsided TMT scientists (see Physics Today, August 2015, page 24

In April the state appointed retired judge Riki May Amano to preside over a new permit request. Telescope opponents objected to the choice. To reduce the likelihood of that opposition putting the final outcome of the hearing at risk, the TMT project and the University of Hawaii (UH)—which as the land leaseholder is applying for the permit on the project’s behalf—also filed briefs to replace her. In early June, the state decided to retain her. “The process doesn’t go in a straight line,” says TMT project manager Gary Sanders, but it is proceeding.

Meanwhile, in a good development for the TMT, the state passed a law this past May that sends appeals in such cases directly to the state supreme court. “I think the most likely scenario is that the University of Hawaii will get the permit. The basic merits haven’t changed,” says Simons, a member of the Maunakea Management Board, a liaison between the UH office that oversees the science reserve on the mountain and the broader community. Should the permit be granted, the expected appeal by protestors would be sped up by bypassing the lower courts.

The whole sky

Mauna Kea is universally recognized as the best site for optical and IR astronomy in the Northern Hemisphere. The combination of gentle trade winds passing unperturbed over the Pacific Ocean and the gradual slope of the 4200-meter Mauna Kea shield volcano creates stable atmospheric conditions at the summit. As Günther Hasinger, director of the UH Institute for Astronomy, puts it, “stars don’t twinkle as much here.” In the Southern Hemisphere, several sites in northern Chile are similarly spectacular for astronomy. That country makes a point of welcoming telescopes (see Physics Today, January 2012, page 20

The TMT partners—Caltech and the University of California in the US, plus Canada, China, India, and Japan—chose Mauna Kea over Chile because of the observing conditions and the potential for synergy with existing telescopes. The 8-meter Japanese Subaru, for example, has a wide field of view that is unmatched among 8- to 10-meter-class telescopes. “We [at Subaru] have many ongoing projects to identify faint targets for TMT,” says Masanori Iye of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan and a member of the TMT governing board. He and astronomers at other Mauna Kea telescopes also hope to reduce costs by sharing operations.

Two other giant telescopes—the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) and the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT)—are under construction by international teams in Chile (see Physics Today, August 2015, page 24

“With the [39-meter] E-ELT and the 25-meter GMT already decided and started, I think the world community needs a telescope of this size in the north,” says Rafael Rebolo, director of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands. If the TMT has to move, he says, it would still be a success at the institute’s primary site on the island of La Palma. Besides La Palma, the TMT team is evaluating Northern Hemisphere sites in China, India, and Mexico.

A balancing act

There is a sense in Hawaii that the TMT has become a focus for broader discontent in some segments of the native Hawaiian population. That prominence raises the stakes in the state’s efforts to balance conflicting demands. In May 2015 Governor David Ige laid out a 10-item action plan for UH to improve its stewardship of Mauna Kea.

A year later, on 26 May, the university published an update detailing the steps it has taken in response to each of the 10 items. It indicates that three have been completed and the others are under way.

For example, the university reaffirmed that the TMT site would be the last new one on Mauna Kea; any future telescopes would be built on existing sites. And the university has selected three telescopes for decommissioning. The process has begun for the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory and the UH Hilo Hoku Kea educational telescope. The third, UKIRT, is to be fully decommissioned by the time science operations commence on the TMT.

The governor also told the university to retain stewardship of only about 2 square kilometers where the telescopes are located and to hand over stewardship of the other 40 square kilometers to the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources. The two parties are working on a memorandum of understanding to that effect. The transfer adds to confusion about stewardship and about the land boundaries for a repeat environmental impact statement that the governor also asked UH to undertake.

Another potential sticking point for the TMT is long-term access to Mauna Kea. The current lease from the state to UH expires in 2033. Its renewal has become tangled up in the opposition swirling around the TMT. It makes sense to build the TMT—which is slated to see first light around 2026—only in a place where it could be used by astronomers for decades.

If the lease is not renewed, “it would be the end of astronomy in Hawaii as we know it,” says Hasinger. Ige has said a renewal should be for a shorter time than the current lease’s 65 years. Looking on the bright side, astronomers interpret that statement to mean there will be a new lease. Simons and others are “working feverishly” on resolving the conflicts with telescope opponents in the hope of facilitating the lease renewal process, he says. Polls conducted last fall suggest that 88% of Hawaii residents agree it should be possible for local culture and science to coexist.

Still, ongoing improvements to the existing telescopes on Mauna Kea are overshadowed by the uncertainties of the TMT. The role of the 8- and 10-meter telescopes will change with the advent of 30-meter-scale telescopes. The future of the TMT “influences decisions about strategic instruments,” Hasinger says, “and building an instrument takes about 10 years. The uncertainty we have now is sending a chilling effect to all developments.”

The TMT’s greatest enemy could be time; opponents have said they will stall the project as long as possible. The April 2018 deadline represents “a date by which the process for Hawaii and for exploring the alternatives” can be accomplished, says TMT project manager Sanders, “and for which the delay—although unwelcome and painful—is tolerable for the project.” To start construction in 2018 on Mauna Kea, the permit would have to be granted by early next year to align with funding cycles of member countries, and Hawaii “would have to enforce the law to provide access that is safe and continuous,” he says.

“We want to build a telescope and do the science,” says the University of Toronto’s Ray Carlberg, one of Canada’s representatives on the TMT board. “There are other mountains in the world. If Hawaii wants us there, they need to make it possible for us to build on a reasonable time scale.”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org