Sanctions on Iran slow science, slam a scientist

DOI: 10.1063/1.3480068

“We feel the noose tightening,” says Hashem Rafii-Tabar of the Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM) in Tehran, referring to the United Nations sanctions against Iran. On 9 June the UN Security Council passed new sanctions, mainly targeting businesses and banks, to curtail Iran’s nuclear program. It’s the fourth round of sanctions since 2006. One individual is also included: Javad Rahighi, a nuclear and accelerator physicist who says he has been singled out mistakenly.

The UN sanctions add to restrictions put in place by the US and the European Union (EU) that, combined with internal unrest, hamper Iran’s interactions with the international physics community. They make it difficult to go abroad for meetings or sabbaticals, to attract visitors, and to buy research equipment. It’s too early to know what impact the latest sanctions will have, but Reza Mansouri, director of the Iranian National Observatory (INO) and a former vice minister of science, says that although the research community does suffer, “the psychological effect is much more severe than any real effect.” At the same time an attitude exists that “it is hard to intimidate Iranians, whether it is a confrontation with a foreign force or it is the opposition to internal repressive agents,” as IPM string theorist Farhad Ardalan puts it. “Iran has been under various types of sanctions for the last 30 years, and life has been going on. So has research.”

Low sales, no service

“The sanctions have affected all areas of life in Iran,” says Rafii-Tabar. “In my own area of research, we try to apply our knowledge to such areas as biomedical nanosensors for early detection of cancer biomarkers and neuronal activities. My work is completely theoretical and computational, but even I have been affected. You cannot buy workstations or supercomputers.” Scientific software—even free software—can be hard or impossible to get, he says. “When you click [on a web link, the source site] recognizes the IP address as being in Iran and a message comes through that we cannot download. Our fear is that soon we might have difficulties accessing the internet.”

To buy a scanning electron microscope or other “equipment we desperately need,” Rafii-Tabar says, “you cannot approach any company. Not in the US. Not in Japan. They would not look at us. They do not respond to our email.” Even if the planned application is purely scientific, if the equipment is considered dual purpose it falls under the sanctions. “They can make a case for anything that you could use it to do something illegal,” says Rafii-Tabar.

Hadi Hadizadeh, a nuclear physicist at Ferdowsi University in Mashhad, tells about a colleague in health physics who tried to buy a phantom model of the human body. “It is stuck in Dubai. He couldn’t get it here to Iran,” says Hadizadeh.

Dubai is one of several way stations through which items are sent to Iran. Much scientific equipment is purchased—at double or more the usual price—through the black market. In Dubai, Azerbaijan, or Cyprus, for example, “middlemen buy the goods for you,” says an Iranian scientist who wants to remain anonymous. There is no guarantee that you get what you ordered, he adds. Sometimes a “Chinese knock-off” is passed off as the original American version. And, of course, there is no service on equipment from abroad, whether it was purchased legally or not.

Even for things that can be legally sent to Iran, many countries don’t deal with Iranian banks. For example, says Rafii-Tabar, “from the point of view of the UN, medical equipment is exempt from the sanctions. So theoretically you can obtain an fMRI [functional magnetic resonance imaging machine]. Companies are willing to sell. But, practically, we face all sorts of difficulties because of regulations to do with banking.”

Diminishing the effects

Scientists involved in international collaborations and those who need sophisticated equipment in their labs suffer the most from sanctions, says Hadi Akbarzadeh, a computational condensed-matter physicist at Isfahan University of Technology and president of the Physics Society of Iran. But, he adds, “sanctions are not a new issue in Iran, and we have experience to diminish [their] effects.”

Along those lines, Omid Akhavan, a physicist at Sharif University of Technology, notes that scientists and engineers have learned to make “some of the required accessories” and to maintain equipment without the support of the manufacturer. An example is homegrown industrial-scale fabrication of high-vacuum facilities. Ultrahigh-vacuum equipment and parts, “which are forbidden to us,” are not far behind, Akhavan says.

Sanctions imposed by Europe and the US have also led to closer collaborations between scientists in Iran and other parts of the world. Akhavan says that the increasingly severe UN sanctions may act to “further strengthen the ties between Iran and free countries in Asia and Latin America.”

Visa vexations

The UN sanctions are compounded by events in Iran. The protests after last year’s presidential elections, for example, scared off visitors and forced the cancellation of international scientific meetings in the country. And, to the frustration of many Iranian physicists, getting a visa takes longer than it used to, and whether someone gets one seems to be random. “A lot of our young scientists are afraid to apply for visas, especially for the US,” says Rafii-Tabar. “They have to go to a US embassy in Dubai, for example. They spend money. They have to be fingerprinted, their eyes are imaged. And there is no guarantee they will come back with a visa. It’s very disheartening.”

Visa delays are common, and not just for people wanting to enter the US. Akbar Jafari, an assistant professor of physics at Sharif, went to France in January, a month later than he had planned to go. “Fortunately, it was just to meet colleagues. If it had been for a conference, I would have missed it,” he says. In the end, “they gave me the visa and said, ‘You have to fly the day after tomorrow.’ I felt humiliated to have to wait a month for a visa, when that would not have happened if I was not from Iran.”

Jafari had a worse experience with Japan. He was invited to go for a month last summer to collaborate with his former postdoc adviser, with whom he had worked from 2004 to 2006. Eventually, he says, “my host asked me to cancel my visit. He said government people were asking him to explain.” Jafari later received some elaboration: “It seems that my acquaintance with superconductivity is going to limit me, as the sanctionists think superconductivity has to do with nuclear research.”

Difficulty in obtaining a visa is field dependent. The Iranian government offers to pay for 9- to 12-month stays abroad for PhD students. “But those in nuclear physics can’t get a visa,” says Hadizadeh. “They can’t get to Australia. Forget about Canada, the UK, or America. Right now I am encouraging people not to go into this field. Not until we somehow develop better relations with some developed countries.” (See the interview with Hadizadeh in Physics Today, July 2005, page 30

In astronomy, says Mansouri, “we have had no problems” attending conferences, participating in international projects, or sending students for training on international telescopes. The INO is a 3.5-meter optical telescope still in the design phase. “Without sanctions, the project would go ahead more smoothly and be better quality,” Mansouri says. “But sanctions will not stop the project. We may not have the best image quality, but we will have a piece of sky no one else has.”

Despite the restrictions, last year the US hosted some 2000-2500 students and researchers from Iran, according to Norm Neureiter, a senior adviser to the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The visa problem is severe and affects many scientists from many countries, including Iran, he says. “I am convinced we are doing great long-term damage to the US scientific enterprise from our present visa policies and processes.”

Physicist fights to clear name

In the UN’s June sanctions against Iran, the sole individual included under “individuals and entities involved in nuclear or ballistic missile activities” is Rahighi, who is listed as “Javad Rahiqi: Head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) Esfahan Nuclear Technology Center.”

Rahighi, who says he learned of the UN sanctions from television reports, says, “It is paralyzing my life. Even if I spend all my properties, everything, I have got to clear my name.” If the UN has information beyond its apparent misidentification of Rahighi as head of Iran’s nuclear program, it’s not saying. A UN spokesperson would say only that the sanctions against Rahighi are “related to confidential information.”

Rahighi earned his PhD in nuclear physics at the University of Edinburgh and did postdoctoral work in England and Belgium. He worked at AEOI’s Esfahan Nuclear Technology Center (ENTC) from 1986 to 1991, and then spent nearly 20 years in AEOI nuclear physics departments in Tehran before moving last November to the IPM, where he heads an accelerator physics group.

Mohammad Lamehi-Rachti, a longtime close AEOI colleague now also at the IPM, says Rahighi’s “activities have had nothing to do, either directly or indirectly, with the enrichment of uranium or the nuclear cycle. I affirm that he is in no way a part of the activities that the security council of the UN is accusing him of.” Adds Mansouri, “He is just a scientist, like more than 500 others working for AEOI. He has never been head of ENTC. Every man in the street in Tehran knows it!”

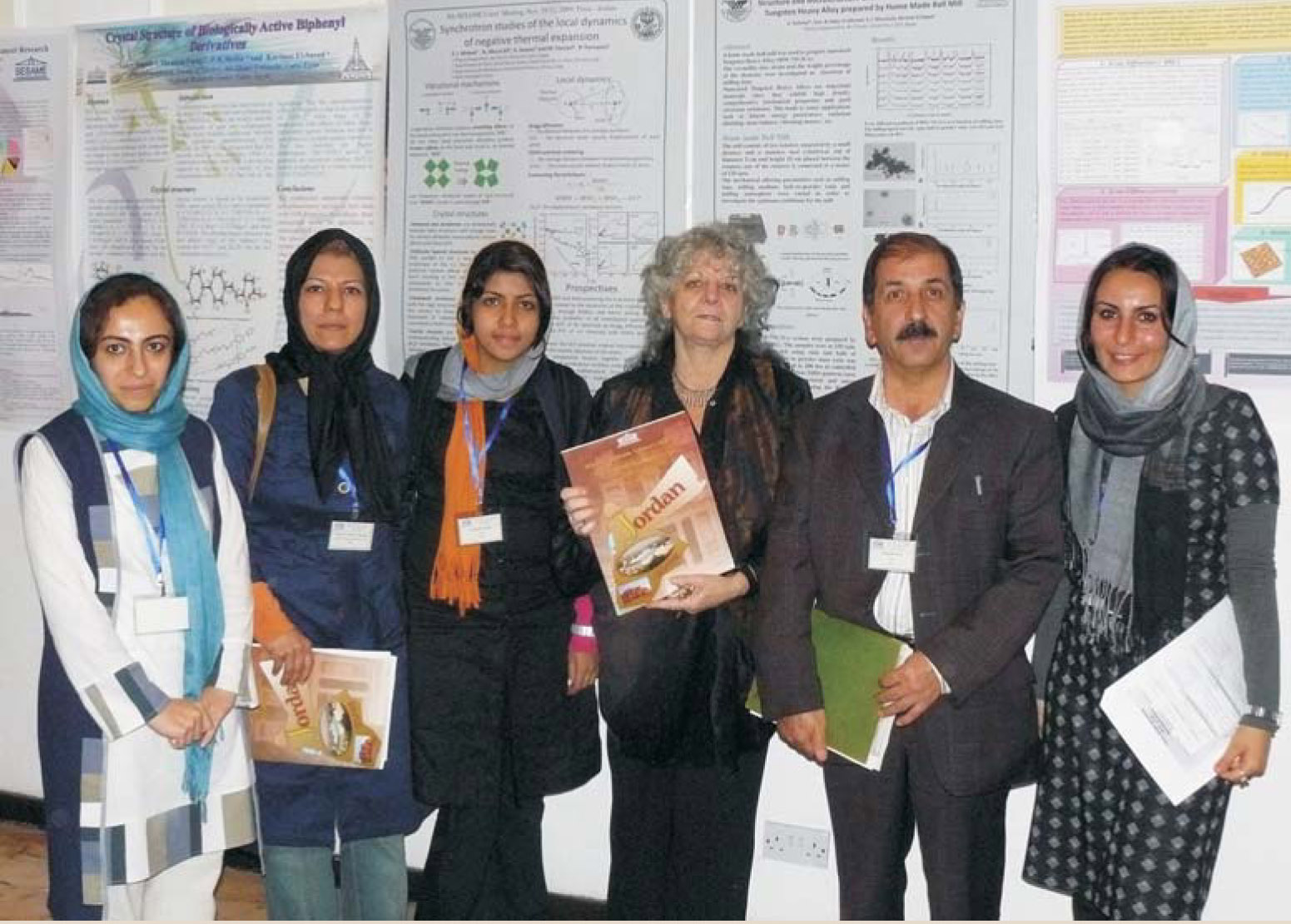

Rahighi chairs the training committee of SESAME, the international synchrotron light source being built in Jordan that is intended to promote peace through science. Herman Winick, a retired SLAC scientist who has been with the project since its inception, says Rahighi “has done an exemplary job. Largely due to his efforts we [SESAME] have money to send people from the Middle East to light sources around the world.” Rahighi’s situation, Winick adds, is “a human tragedy and Kafkaesque.”

Rahighi also chairs a committee to build a national synchrotron light source in Iran. After the UN sanctions became known, some senior scientists hinted that his status could hurt the project. Rahighi has offered to step down.

The new sanctions overshadow sanctions imposed by the EU in 2008. After an appeal failed, Rahighi wrote to the EU this past March asking for his case to be reconsidered. “They have made a mistake and they don’t listen to correct it,” he says.

Support and suspicions

So far, help for Rahighi is coming from the IPM, which has offered to pay for an international lawyer. Akbarzadeh says the Physics Society of Iran “will do its best to [help Rahighi] regain his credibility.” And Rahighi has word that the current president of the AEOI will write a letter certifying that Rahighi was never head of the ENTC nor affiliated with the Nuclear Fuel Production and Procurement Company.

The American Physical Society’s Committee on International Freedom of Scientists (CIFS) is looking into whether and how to try to help Rahighi, according to committee chair Noemi Mirkin of the University of Michigan. Yousuf Makdisi, a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory who was involved in a letter CIFS wrote to the EU in support of Rahighi in August 2009, says that “his name doesn’t appear on any undesirable lists in the US”—most notably one on nonproliferation. But, Makdisi adds, it’s impossible to verify that his hands are clean.

According to Ardalan, who has known Rahighi for about a year, “people who don’t know him assume that he must have done something. [They assume that] the UN must have crosschecked, so they are suspicious.” Ironically, he says, the UN sanctions may lead to support of Rahighi by the current Iranian regime, which in turn will make people more suspicious.

“These sanctions make me all the sadder,” says Lamehi-Rachti, “because through Rahighi, they attack our entire scientific community. Is it a crime to teach and do research in the field of nuclear physics? Is it a crime to show young people that science is a tool to support the development of our country and an instrument in the service of peace?”

A replacement battery for this neutron monitor can’t be bought in Iran due to UN sanctions. The box is a battery that graduate students working in the lab of nuclear physicist Hadi Hadizadeh taped onto the back of the unit so they can take it into the field; the original battery sits inside the monitor. The white globe thermalizes fast neutrons to make them detectable. One use is to detect landmines.

HADI HADIZADEH

Javad Rahighi (second from right) with Ada Yonath (third from right) of Israel, a 2009 Nobel laureate in chemistry, and several students at a SESAME users’ meeting in Jordan last November.

ELIEZER YAARI/JERUSALEM

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org