Rumor mills spread word on who’s hot and who’s hiring

DOI: 10.1063/1.2754595

Joanne Cohn has on occasion dashed off an e-mail saying that so-and-so got an interview at such-and-such an institution. “I would just feel like it. Some people are information junkies and help pass information around,” says Cohn, a member of the astronomy research staff at the University of California, Berkeley, who, with her husband, UC Berkeley astronomer Martin White, last year launched a new astronomy jobs rumor mill—the first as a wiki, a format that allows anyone to edit entries.

Web-based jobs rumor mills saw their start in theoretical particle physics in 1994. John Terning and Michael Dugan were postdocs at Boston University when, frustrated with the job market—Dugan had been a postdoc for 10 years—they started keeping tabs online of current academic job searches in their field. “We would talk to our friends at MIT and Harvard,” says Terning. “We had a good idea of who was being interviewed and who was getting jobs.” Dugan left research a year later; Terning hung on and in 2001 landed a faculty position at UC Davis. At that point he shed his anonymity, but he continues to moderate the jobs rumor mill he created.

In the meantime, similar jobs rumor mills have sprung up in other fields—including experimental particle physics, astronomy, and nuclear theory. Another site combines theoretical and experimental condensed-matter physics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; and biophysics. They post job openings, and as the academic hiring season progresses, shortlists are added, followed by the names of people who are offered positions, and finally whether they accept or decline.

Less asymmetry

Some moderators try to verify the rumors sent to them, and some check whether it’s okay to post people’s names. On other rumor mills, anything goes: “John Doe,” the anonymous moderator of the CM/AMO/biophysics jobs rumor mill, says he verifies rumors if he can, “but these are rumors, after all.” And, he adds, “I have on several occasions received requests from people on shortlists that their names be taken down, but never complied.”

The rumor mill “plays an interesting role in making information that used to be private very public and accessible to all levels of people,” says Priya Natarajan, a young astronomy professor at Yale University. For candidates, says Mark Krumholz, a postdoc at Princeton University who has accepted a faculty position at UC Santa Cruz, the rumor mill “reduces the asymmetry. Potential employers can find out who is on what shortlist even without the rumor mill. Job seekers can’t.”

The main advantage of the rumor mill, Krumholz continues, is that “it lets you know when you are out of the running.” For one job he didn’t get, he says, “The only way I know is from the rumor mill—my application vanished into a black hole. The rumor mill lets you know where you stand when departments don’t.” Regarding the new wiki format of the astromill, Krumholz adds, “It’s vastly superior. It makes it more accurate and up to date. And it makes it possible for people to keep themselves off the page.”

The rumor mill can also be useful for faculty, especially when the subfield of a potential hire is undecided, says a physics professor who wanted to remain unnamed. “By knowing what the competition is, you can argue that your candidate is better.” Adds Bira van Kolck, a nuclear theory professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, “If you know that your second, third, and fourth choices have offers elsewhere, you might try to move faster with your first-choice candidate.”

Hot candidates

Apotential downside, says Tom Cohen, a professor of nuclear theory at the University of Maryland, College Park, is the risk that committees focus more attention on the people who are on shortlists. “This would be pernicious,” he says. “I don’t think it happens much, but I’m sure there is some subtle effect.”

While some faculty members say they look at the rumor mill during searches, others say they make a point not to—and still others haven’t heard of it. Regardless, they maintain that their searches are not influenced by rumors. That runs counter to the perception among junior-level researchers, however. “Being on multiple shortlists raises one’s stock,” says Krumholz. The rumor mill “unfairly amplifies the chances of the top four or five people in the candidate pool in any given year,” adds an astronomy postdoc who requested anonymity. “I hear people talk about ‘well, we should interview that person because our rivals are interviewing them.’”

“Committees are people,” says Dan Ralph, a solid-state physicist at Cornell University. “There is a lot of positive feedback in this business. If it looks like one school is getting excited about a candidate, things can start to snowball and it can affect the opinions at other places.” In some years, he adds, “if we’ve been interested in quite junior people, or we have found someone who seems great and we don’t want everyone else to make them offers too, we have been secretive and blocked access to our seminar list from off campus.” But, he says, a candidate can become hot “with or without the rumor mill. There’s enough information about these things. It might happen faster [with the rumor mill], but qualitatively the rumor mill doesn’t change the dynamic.”

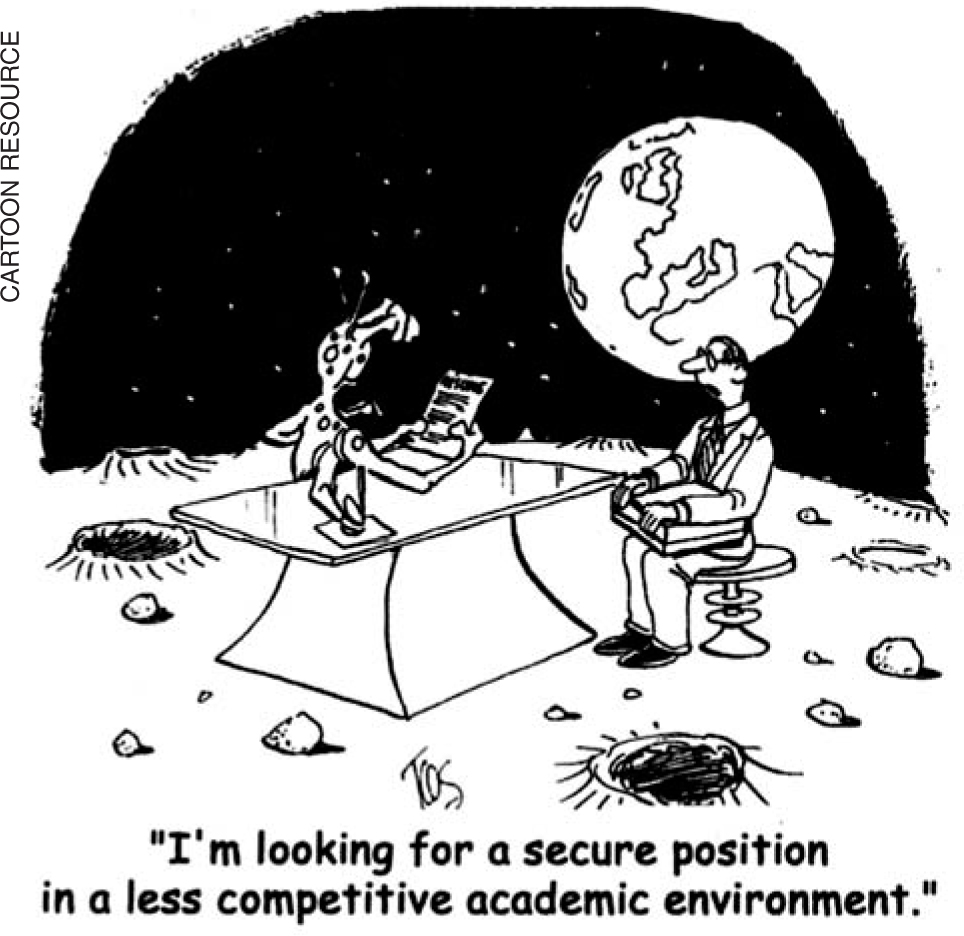

“I’m looking for a secure position in a less competitive academic environment.”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org