Particle physicists brainstorm long-term collider options

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2444

Even as the US high-energy physics community is working to keep a world-class program for the next 10 years (see story on page 18

The Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) in Beijing and CERN near Geneva have similar visions: Each might start with an electron–positron machine—perhaps 240 GeV in China and higher in Europe—and then convert to a proton–proton facility with center-of-mass collisions up to 100 TeV, about seven times as high as planned for the next stages of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

The China high-energy physics community, says IHEP director Yifang Wang, is looking for a successor to the 240-m Beijing Electron Positron Collider. For now, he says, “we are focusing on a 50-km ring as the lower limit for creating a Higgs factory.” A possible location has been scoped out in Qinhuangdao, some 300 km east of Beijing. Wang lists money, manpower, and technology as the top challenges. Export controls could also put a monkey wrench into importing crucial know-how.

In February IHEP launched the Center for Future High Energy Physics to attract students into the field, garner support among scientists for a future collider in China, and show the Chinese government that the local and global physics communities are behind the idea.

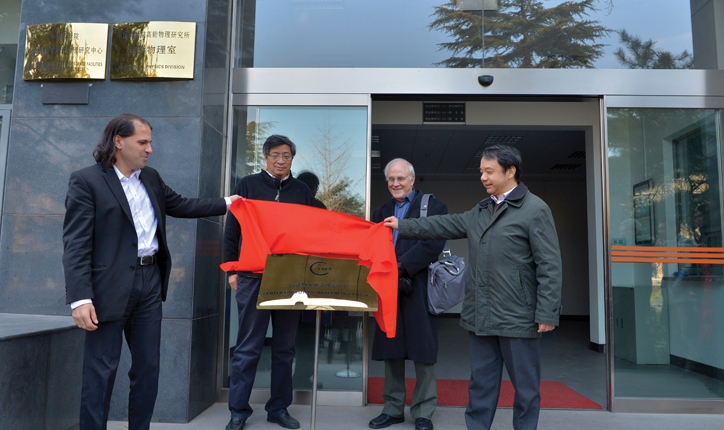

The opening ceremony of the Center for Future High Energy Physics in Beijing attracted many scientists, including (from left) Nima Arkani-Hamed of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, the center’s founding director; Hesheng Chen, former director of the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing; David Gross, director emeritus of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara; and IHEP director Yifang Wang.

IHEP

Nima Arkani-Hamed, a theoretical physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, is director of the new center. “I became convinced that they [in China] are serious, and there is a nonzero chance of it happening. This project is something you can be guaranteed to be world leader in if you build it.” Proponents hope that the promise of prestige could persuade China to invest new money into the field—and that such a project could move faster and cheaper in China than elsewhere. “It’s good for China, and it’s good for physics,” says Arkani-Hamed.

CERN scientists have their eye on a 100-TeV proton–proton collider that would go under Lake Geneva so as to exploit the existing CERN infrastructure. “What 100-TeV center of mass would give you is lots of high-energy collisions,” says John Ellis of King’s College London. “If you go much below that, you won’t open up as much phase space for new physics.” Areas of discovery might include dark matter, supersymmetry, and the origin of the matter–antimatter asymmetry in the universe.

A future circular electron–positron collider would scientifically overlap the design-ready International Linear Collider (ILC), which Japan is considering hosting (see Physics Today, March 2013, page 23

In China, the plan is to prepare a proposal for R&D funding by the end of this year. In Europe, where money and personnel are currently wrapped up with the LHC, scientists aim to include a circular collider in the next European Strategy for Particle Physics, on which work begins in 2018. The two teams are cooperating and generally concur that at most one 100-km-scale collider would go ahead. The IHEP scientists are taking RMB 20 billion ($3.2 billion) as a preliminary cap for their electron collider. For a 100-TeV hadron machine, says Ellis, “it’s premature to estimate. Everyone has in mind 10 billion of your favorite currency unit.”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org