Old satellite dishes become new telescopes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1213

“It’s not a new concept, but now is the time,” says Justin Jonas, associate director for science and engineering with the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) South Africa Project. With optical fibers replacing satellite communications dishes, radio astronomers around the world are converting the obsolete dishes into telescopes. Many dishes across Africa, for example, have been identified as conversion candidates, and one in Ghana is set to go forward. The UK’s Goonhilly Earth Station, which in 1962 received the first transatlantic television broadcasts, is getting a makeover. Other recent or planned retrofits can be found in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and elsewhere.

“Adding one telescope doesn’t make a scientific revolution, but if you could double the number [in the European Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network (EVN)], that would revolutionize our field,” says Huib van Langevelde, director of the Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe, based in Dwingeloo, the Netherlands. “Our images would be much more accurate and look better, and we could sample a larger number of sources.”

Many recycled dishes are also used to train students and to promote science in developing countries. In Peru, whose universities do not offer astronomy degrees, José Ishitsuka is overseeing the transformation of a 32-meter satellite communications dish into a single-frequency telescope that will be dedicated to observing methanol masers from emerging stars. Once the telescope is running, says Ishitsuka, “it will allow young people to do research and write papers on the world level.”

The Africa gap

A few years ago, failed bearings temporarily shut down the Hartebeesthoek radio telescope near Johannesburg, South Africa. With time on his hands, observatory director Mike Gaylard discovered some two dozen 30-meter satellite dishes in as many countries in Africa. “I tracked down a whole lot with stamps and Google Earth,” he says, noting that many countries issued postage stamps to mark a satellite dish’s inauguration. Although some dishes have been scrapped, he says, “there are dishes in Kenya, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe. . . . It’s quite tantalizing for a radio astronomer to consider linking antennas to the VLBI networks.”

“Africa is really quite interesting for radio astronomy,” says van Langevelde. The EVN does not “have the sensitivity for things extended in the north–south direction because we only have that one telescope [Hartebeesthoek] in South Africa. The whole African continent is a blank spot in our vision.”

“We want to identify antennas in Africa to fill the gap,” says Jonas, “and at the same time put some flesh onto collaborations.” Such collaborations began as part of South Africa’s bid to host the SKA—the world’s largest radio astronomy array, for which a site decision between that country and Australia is expected next year. “We are going to establish the Africa array whether or not the SKA occurs here. And it’s something we can do in the next few years, for a fairly small investment.”

Retrofitting a satellite dish involves installing new receivers, fixing or replacing steering mechanisms and electronics, and adding telescope control software, maser clocks for interferometric measurements, and sometimes fiber-optic connections. The cost of refurbishing a dish ranges from $100 000, like the project in Peru, to a couple million dollars, about one-tenth the cost of building a new 30-meter radio astronomy telescope.

Ghana, for one, jumped at the opportunity to retrofit when it was proposed by astronomers from South Africa. A defunct satellite dish about 30 km northeast of Accra, the capital city, will become the flagship of a planned space science and technology center, says Adelaide Asante, a research officer in Ghana’s science and technology ministry. With no radio astronomers in the country, Asante notes that the new center will stress both training and research. “In a developing country, you have to balance research with what the facility can do for the country.”

A commercial approach

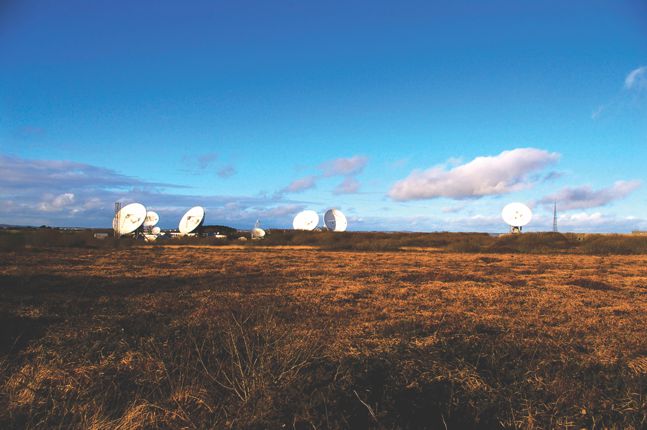

The Goonhilly conversion combines radio astronomy with two potentially moneymaking ventures: a spacecraft tracking business and a visitors’ center. Last January partners in academia and industry kicked off the effort to save the site. Ian Jones, who worked in telephone and aircraft communications at Goonhilly in its heyday, is leading the charge.

One of the site’s three 30-meter-class dishes will be for radio astronomy, one will be dedicated to tracking spacecraft, and the third will be equipped for both uses. Some of the site’s 15-meter dishes will also be fixed up for use in a local interferometer and for training students.

Although the Goonhilly dishes could be used on their own, the prospect of linking to the UK’s e-MERLIN interferometer is what really has radio astronomers excited. With Goonhilly, e-MERLIN’s baseline would grow from about 217 km to 400 km, doubling the interferometer’s resolution. Because of its location, Goonhilly would also improve the resolution looking south.

An extended e-MERLIN could study star and galaxy formation, black holes, protoplanetary disks, and, with gravitational lensing, dark matter located between Earth and distant radio sources. The interferometer would have similar resolution to the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, says the University of Leeds’s Melvin Hoare, who heads the Consortium of Universities for Goonhilly Astronomy. “ALMA can look at cold molecular gases, e-MERLIN is good at looking at ionized gas, so you can get links between molecular and ionized gases.” Such “frontline science” opened up by linking to e-MERLIN “is the real beauty of the [Goonhilly] telescopes,” he says.

The four consortium members signed on to the project in May and have put in cash and in-kind contributions toward their aim of £500 000 ($800 000). That will cover the cost of outfitting at least one 30-meter telescope. They are still seeking roughly £1 million to link Goonhilly to e-MERLIN.

Postage stamps marked the inauguration of satellite communications in many African countries. Now some of those satellite dishes are finding new life as radio telescopes.

GHANA POST

The Goonhilly Earth Station in Cornwall, UK, is being converted to a multiuse site for spacecraft tracking and radio astronomy.

IAN JONES

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org