North Carolina institute offers to archive old astronomy data

DOI: 10.1063/1.3099573

A survey last year of North American institutions holding photographic plates used from around the 1880s until the 1990s to record astronomical data revealed—to nobody’s surprise—lots of plates getting little use. The survey’s findings bolstered the case for a national archive of plates—a role the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute in Rosman, North Carolina, wants to take on. PARI is volunteering to archive such plates and to digitize them to make the data easily accessible to researchers. So far, though, PARI lacks the funds to digitize, and some astronomers say money would be better spent on new science.

Carried out under the auspices of the American Astronomical Society’s working group on the preservation of astronomical heritage, the survey collected such information as numbers and types of plates, locations, storage conditions, availability for use, and actual use over the past 10 years. Nearly 2.5 million photographic plates were identified in North America, with 97% of them in the 16 largest collections. About a third of spectroscopic plates are at Canadian institutions.

“We’ll house them”

PARI started out as a NASA satellite-tracking site and then served as a US Department of Defense communications center during the cold war. It was later turned into a nonprofit radio astronomy and K–12 outreach center (see Physics Today, March 2001, page 26

“If you have plates and don’t know what to do with them, we’ll house them for you,” says PARI astronomy director Michael Castelaz. “People have a choice of donating or storing, where they maintain ownership.” So far, he says, PARI is home to some 50 000 glass plates. As PARI secures funding, he adds, “we will scan and digitize the plates.”

“Most institutions have thought about throwing away their plates. They don’t have the moral courage, but often they can’t provide the necessary environmental conditions for storing them,” says Caty Pilachowski, an astronomer at Indiana University. “On a couple of occasions I have gone back to look at archival data. I do care about it. But [archiving takes] a lot of money.” As for PARI, she says, “will they get the budget to follow through [and digitize]? I think it’s more expensive than they anticipate. And, is the amount of information recovered ultimately worth the cost?”

Looking forward and back

That’s the central question, says David Monet, an astronomer at the US Naval Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, who spent 20 years digitizing plates. “How much of your budget is it worth to go chasing science in old plates? CCDs promise huge amounts of stuff we couldn’t dream of doing with photographs. I’m voting with my feet. We are on the threshold of amazing advances. I don’t care about plates anymore.” But, he adds, “if PARI can come up with a plan to survive the cost-and-effort test, then great.”

Scientists at Harvard University have built a scanner that can handle two plates in one and a half minutes with “phenomenal accuracy,” says Josh Grindlay who leads Digital Access to a Sky Century at Harvard. He estimates that digitizing the university’s full collection—which at more than half a million plates is “one-third of all the astronomical plates in the world”—will take about four years and cost up to $5 million. So far, the team has scanned just a few thousand plates, but DASCH has already made discoveries, including “variable stars of a sort we have never seen before,” says Grindlay. Starting anew, “it would take 50 years to get the data and time coverage we already have. Why wait that long?”

Elizabeth Griffin of the Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics in Victoria, Canada, has been working to save plates for some years (see Physics Today, June 2003, page 30

The cost of digitization is “nothing compared to a space shot,” Griffin says. “Not only are the plates deteriorating slowly because of the natural aging and poor environmental conditions, but the expertise and knowledge of how to deal with them is also being lost. We are trying to energize a recovery movement.”

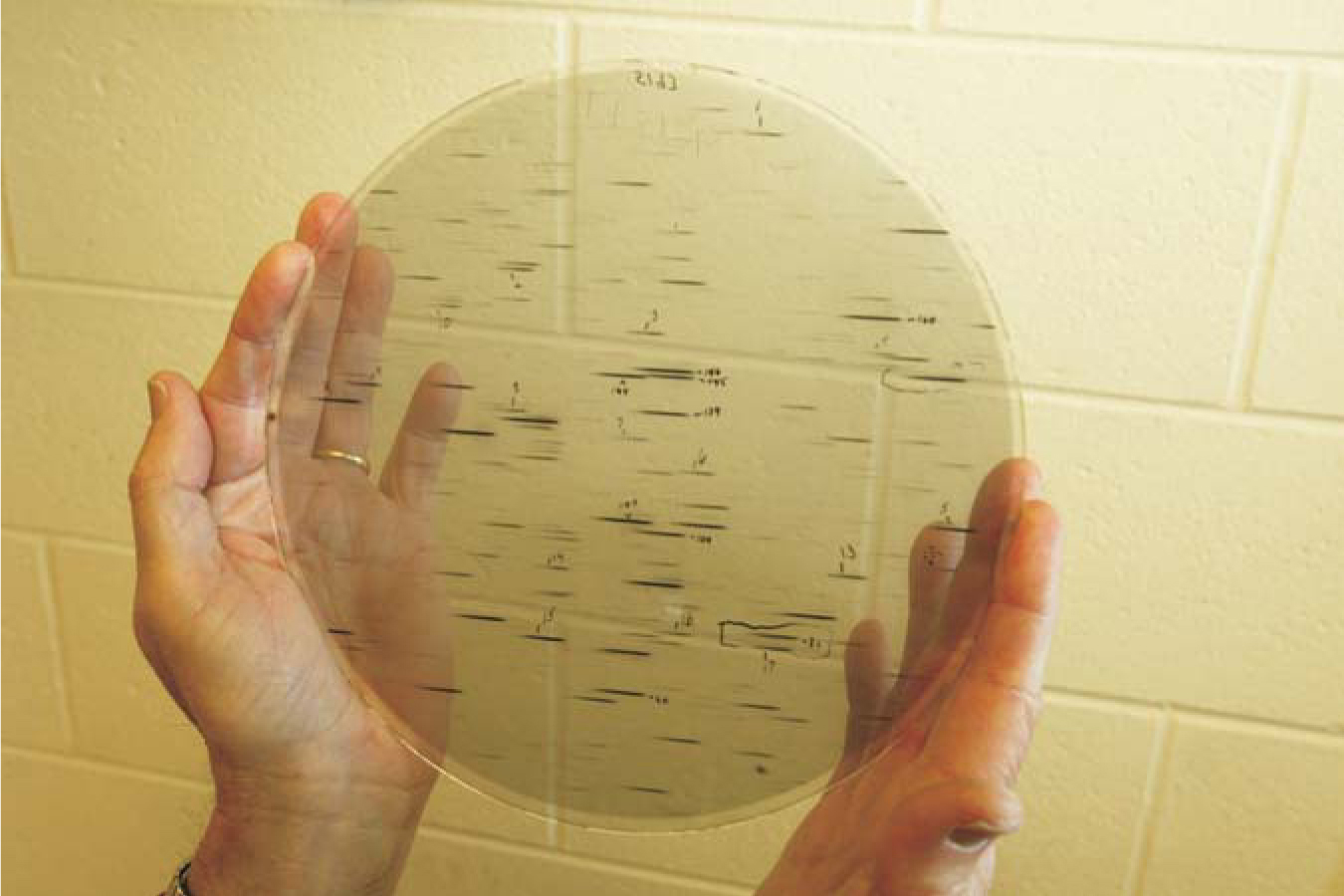

This astronomical plate from the 1950s used a thin prism attached to the telescope to create a spectrum for each star. Such plates are scattered across many institutions; to be accessible for research, they need to be cataloged and digitized.

PEGGY BRISBANE, CMU

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org