Italy’s students protest government attack on universities

DOI: 10.1063/1.3047664

“Italian universities are in a serious crisis,” says Federico Ricci-Tersenghi, a physicist at the University of Rome I (“La Sapienza”). A new law that threatens the country’s universities has prompted ongoing protests. On 30 October, for example, a country-wide strike of schools from primary through university drew about a million demonstrators in Rome alone. “What’s going on in Italy is extraordinary. The streets are full. I thought Italy had fallen asleep,” says University of Florence astrophysicist and former International Astronomical Union president Franco Pacini.

In the past, says José Lorenzana, a physicist at Italy’s National Institute for the Physics of Condensed Matter, the government has periodically blocked hiring for permanent positions, which created conditions for a later mass hiring. “What we need is a constant flow of researchers,” says Lorenzana. “Instead, the government is reducing hiring in a draconian way.”

The new law cuts government funding to universities, gives public universities the option of becoming private foundations, and restricts hiring to 20% of vacated positions; it also makes a hodgepodge of funding cuts in other sectors of the economy. The government justifies the law and its urgency by saying that many measures must be taken to satisfy the financial requirements of the European Union. “The Berlusconi government is showing respect [for the EU] when it comes to cutting the budget, but not when it comes to reaching goals,” says Pacini, referring to the Lisbon agreement, which sets a goal of investing 3% of gross national product in research and development by 2010.

“Empty departments”

Under the new law, public funding for universities will decrease in stages by a total of €1.5 billion ($1.9 billion)—with cuts starting at 1% in 2009 and growing to 7.8% in 2013. The budget cut is the least problematic, says Ricci-Tersenghi: “You can increase tuition for students. That’s a social problem but it can be solved somehow.” Still, public spending per college student in Italy is already lower than in many other developed countries.

Privatizing public universities is a new option, Ricci-Tersenghi says. “We have no idea how many will decide to transform. The freedom in managing money and people may be one reason for a university to change. They could choose the type of contracts to give people and could save a lot of money in salaries.” In proposing that universities become private, the government refers to US universities, Ricci-Tersenghi adds. “But Italy is not in the habit of donating to universities. Most will die because they won’t find money.” At his university, he says, state money makes up a large fraction of funding, “so transforming to a private enterprise and saying no to money from the state would be difficult.”

For universities, the most damaging aspect of the new law, at least for now, is the turnover limit, says Ricci-Tersenghi. “We can hire one person for every five retiring. Even if five full professors retire, we can hire just one person at the lowest entry level.” The hiring restriction “means we will empty departments and lose people.” Adds Pacini, “It could take decades to rebuild.”

Outrage and hope

The Berlusconi government used a decreto legge (decree of law) to enact the law as an emergency measure and thus circumvent the usual debate in parliament. After passing in the cabinet, says Ricci-Tersenghi, “it goes to parliament just for a yes or no. There is no discussion, no modifications. If they say no, there will be new parliamentary elections. It’s a drastic choice.” Adds Lorenzana, “It was proposed by the minister of the treasury. The funny thing is that the minister of research and education, [Mariastella] Gelmini, did not protest. She is silent.” The decree was put forth on 25 June and approved by the parliament on 6 August.

“Nobody knew [about the new law] because they were on holiday and universities were closed,” says Laura Caccianini, a third-year physics student at La Sapienza. “So when we came back to our lessons, we also started studying the law, trying to understand its consequences. Then we understood that it would destroy universities. It’s unbelievable. We started protesting.” At her university, she adds, the leaders in the protests are a group of undergraduate physics students. Even at the faculty level, says Ricci-Tersenghi, “historically, the physics department is one of the most politically active.”

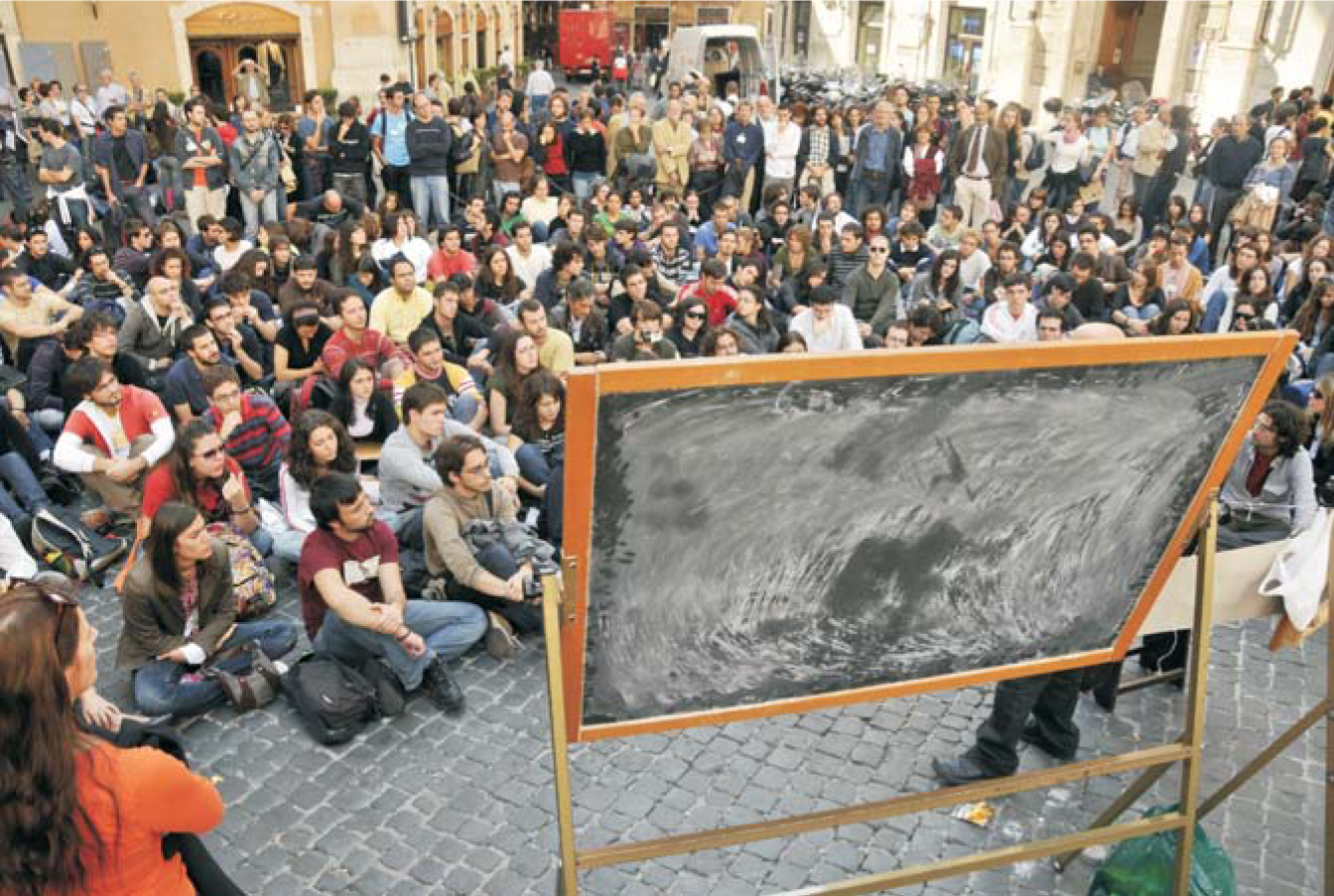

Since early October students have been holding demonstrations, marching in the streets, and occupying university buildings. Their protests have also taken more creative forms, such as posting ads selling researchers and universities on eBay, posting videos on YouTube, spelling out “NO 133” (the name of the law) with candles, and floating a sinking boat in La Sapienza’s central fountain to represent public research—figures leaving the boat symbolize brain drain to the US and France. In addition, professors are delivering lectures in front of the parliament building. “In every city—Rome, Venice, Naples, Milan, Florence—students are mobilizing,” says Caccianini. “When we started our protests, we thought it was unrealistic [to hope the law would be changed or revoked]. But now the protests are huge—every student tries to work against this law. Our hopes are growing day by day.”

“According to people who lived the university protests of the sixties and seventies of the 20th century, the major difference is that now the protesters are among our best students!” says Ricci-Tersenghi. “The reason is clear: The present law is cutting the future of the most brilliant students, those who had a chance of entering the research system.”

As for the government, Ricci-Tersenghi says, “It has declared itself against knowledge. It is trying to destroy public education at all levels. We don’t expect them to change the law. Especially with 60% support from the population.” Instead, he says, the academic community hopes the government will incorporate suggestions into the drafting of a hinted-at reform: “We are saying, Please distribute the money—and the cuts—according to some evaluation. The only hope is to cut pieces of the university that are not as good as the average. Our second message is, Allow some entering channel for young people.” The past government promised €20–40 million for recruiting young faculty members. “If the turnover is kept so low,” he says, “we won’t be able to use this money. So our suggestion is to let us use this specific money to hire young people—independent of the 20% rehiring.”

“We hope to minimize the damage,” says Ricci-Tersenghi. “The only hope is to allow some selectivity in how the damage is distributed.”

Surprise concessions?

As Physics Today went to press, the Italian government had begun to take notice of the nationwide protests. Says Ricci-Tersenghi, “The protests have decreased the popularity rating for the government. It seems Prime Minister Berlusconi has asked Minister Gelmini to take more time before presenting the reform. And some members of the right wing of the parliament—the ones supporting the present government—have declared they would not accept any reform presented as a decreto legge. This is good news.”

Protests in Italy against cuts to universities are taking many forms, including lectures such as one on 24 October held by Gianni Jona-Lasinio in front of the parliament building in Rome.

INDACO

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842 US . tfeder@aip.org