Hunkered down, academe waits for the full fallout of the economic crisis

DOI: 10.1063/1.3141932

“The situation is pretty uncertain everywhere.” That sums up how US universities are feeling the impact of the economic downturn, says Peter Strittmatter, chair of the University of Arizona’s astronomy department. His university is among the hardest hit so far, with an 18% budget cut; more typical is less than 10%. “The question is, how do the cuts get translated to effects on departments?” says MIT physics chair Edmund Bertschinger. “We have some fat—we have 5% we can cut in the first year. The second year will take some skin. The third year will take an arm.”

The degree of belt-tightening varies and largely depends on endowments for private colleges and universities and on state budgets for public ones. Still, “fat” is taking similar forms from one campus to the next, and it’s often far from painless to trim. The bulk of most university department budgets goes to pay salaries, and an early casualty has been hiring. “It’s the flip side of tenure,” says David Campbell, provost of Boston University, which, he says, “was one of the first places to take action. We froze open staff positions. We allowed faculty searches to go forward, but with the understanding that whether we would fill them would be decided when the department brought in their candidate.” Physics is more expensive than humanities, he adds, because of the large salaries and startup packages, “but you have to pull back across the board and try not to damage the most outstanding units.” (See the story on

“Search canceled”

Last December, Bruce Carney, interim dean of arts and sciences at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, suspended 30 of 106 faculty searches at the college. “The governor’s budget calls for a 6.5% cut to the UNC system,” he says. “We are trying to preserve things that keep the best faculty here. We are growing the honors program, spending money on [faculty] retention packages…. This year we are filling positions more selectively; it’s a buyers’ market. It should improve the quality of the people we hire.”

John Johnson, an astronomy postdoc at the University of Hawaii, says that of the five faculty positions he wanted to apply for last fall, “two of the searches were canceled, and a third had an early deadline—they wanted to hurry up and get in a hire before the budget cuts set in. I didn’t want to rush.” Johnson got offers from Princeton University and Caltech. But, he says, “the [job] rumor mill is littered with ‘search canceled.’”

At most universities, if you ask whether faculty members are getting raises this year, the answer is a snort. One exception is UCLA: “In the 20 years I’ve been here,” says Roberto Peccei, the university’s vice chancellor for research, “there was one salary freeze, in the early ‘90s. That turned out to be a disaster. It engenders so much ill will, it wasn’t worth it.”

Another common casualty is graduate enrollment. “We are admitting two or three fewer [this year],” says Don Candela, head of physics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Typically, 12–15 students enter the university’s physics PhD program. “Normally,” he says, “they get paid as teaching assistants for the first year and a half, and then they go work on people’s grants. We’re trying to twist people’s arms to take on more graduate research assistants earlier. If we don’t do this, then in a couple of years we won’t have enough people to fill our research labs.” Bertschinger expects about a 10% decrease in the number of TAs that MIT’s physics department can support, “but the effect on the graduate pool is much less, since we support our graduate students in different ways.” Graduate stipends, he adds, “are increasing by 3.4% next year. We are giving priority to our students.” At UNC, says Carney, the extent to which incoming graduate classes are limited will be weighed against the number of adjuncts and instructors hired. “It’s how the departments choose to handle this. There is still a lot of decentralization here.”

Cutting costs

Like many universities, UCLA has scenarios for different levels of cuts. Internally, says Peccei, “we’ve been trying to think through a 3% cut, a 5% cut, and an 8% cut and what we would do in each case. There is some reason to think on the pessimistic side.” For an 8% cut, he adds, “it gets aggressive. You have to think about how many courses you offer, reduce the number of courses taught by adjuncts. Travel has been pared to the bone.” Modeling exercises to estimate what MIT’s endowment will pay out, adds Bertschinger, show “a significant drop over the next three years—it could be 15% or 20%. We are expecting it to be hard.”

Other cost-cutting measures at universities include raising tuition, reducing startup packages, cutting computer and administrative support, trimming student services and public outreach programs, offering fewer cultural events, and curbing use of campus cars. “People are minding their paper clips, but salaries are the biggest cost,” says Candela.

At Columbia University, says physics chair Andrew Millis, “We certainly feel the constraints, but we are not at the level where they are having a catastrophic effect. I would characterize it as significant belt-tightening.” The outlook, he adds, “will depend on three things: how quickly the endowment goes back to what it was, which is related to how quickly the international economy recovers; what happens to donations; and tuition revenues.”

“Physics is a program where research and startup costs are high. We spend over $50 000 a year just on liquid helium in my research program,” adds Dale Van Harlingen, physics chair at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “At the 2.5% level [of cuts], we can absorb the budget shortfall by not rehiring to fill vacancies and reducing the number of TAs. At 5%, we have to look into transferring the burden of faculty secretaries onto research funds and losing maybe 10% of our staff. At 10%, unless you can induce retirements, we are looking at losing as much as one-third of our staff—IT people, business-office people, machine-shop capability. A lot of functions done at the departmental level may move to shared services. That can save money, but it loses the personal aspect.”

“We won’t know the total impact for next year until we see the state’s budget,” says University of Arizona president Robert Shelton. “But we are planning on reducing spending by $50 million.” With its particularly tight budget, the university plans to impose furloughs in the next academic year. “We are looking at three to seven days,” says Shelton. “That could save $7 million to $8 million.” UA was struggling financially before the economy tanked, he says. “In the last 16 years, we have had 14 years of budget cuts. The magnitude is new. We are combining the administrative structures of five colleges into one—that will save $4 million or $5 million a year. We have a couple dozen degree programs we are going to eliminate. We are looking at how to deploy faculty’s time optimally. For example, do we need multiple introductory sequences of physics? Maybe we can consolidate to free up faculty time. We will do this as fast as we can—starting this fall.” At the same time, adds Strittmatter, “We continue with our goal of remaining a leading institution in astronomical research. The cuts have been very serious in the university, but some places are shielded like we are.”

Many schools are raising undergraduate tuition. But they are crossing their fingers that tuition revenues don’t drop. “We have reached out to students and told them if they are having financial problems, tell us and we will try to help,” says Boston University’s Campbell. “Every 100 students we lose would cost us $2.5 million a year in tuition alone,” he adds. Meanwhile, community colleges, which are less expensive to attend, are seeing enrollments grow, and some have even begun offering third- and fourth-year courses.

Psychological effects

Exacerbating the tight job market is a slowdown in retirements, especially at places with 403(b)-type retirement plans. “People are not retiring because of their TIAA-CREF [balances] being down 30%,” says Michael Shull, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “This has a ripple effect—it creates a holding pattern of postdocs.” That, in turn, will increase the competition down the road, which could either make the job hunt harder for people who have remained longer in postdoc positions or hurt new PhDs as they compete against more experienced postdocs.

“It’s obvious there will be fewer jobs. This makes me worried about our field,” says Millis. “The rising generation will have a harder time finding a place than did the previous generation of scientists, and there is no systematic plan for dealing with that.” Adds Lars Bildsten, of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, “We are going to have a tragedy unfold if the community doesn’t get together and do something. We’ve trained this cadre, and if there is a five-year hiatus, what happens to these people? In the long run we need them. People are talking about bridging positions”—where outside funding covers the first several years of a person’s salary and the host university picks up later. “It’s in the air, lots of people are talking, but nobody is taking the reins on this.” In canceling searches, he adds, “I think some institutions have overreacted. The smart institutions will see this is an opportunity. That requires a bit of boldness.” Adds Shull, “No one can see around the corner, but so much of this is psychological.”

The bright spot, of course, is the stimulus package, or the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which was enacted in March. “The great hope is that the federal government will fund some university infrastructure. That would help a lot because it would bypass [budget] issues with the states,” says UCLA’s Peccei. “We are expecting highly competitive fields like physics and chemistry to bring in some money. And I think there will be significant money for things like renewable energy.” NSF has announced that the bulk of its ARRA research money will go to grant applications that are already in-house, including some that were rejected since last fall. Says Shull, “It’s wait and watch to see how fast these new grants can be translated into hires for grad students and postdocs.”

Despite the pervasive pinch, the mood in academe is of cautious optimism, says Caltech astronomer George Djorgovski. “I’d emphasize caution. There is an expectation that things could get worse—certainly no one knows the extent of things yet. But the good news is that the new administration is clearly pro-science. The prospects for the future are fine. But in the short term academia is suffering as much as anyone else.”

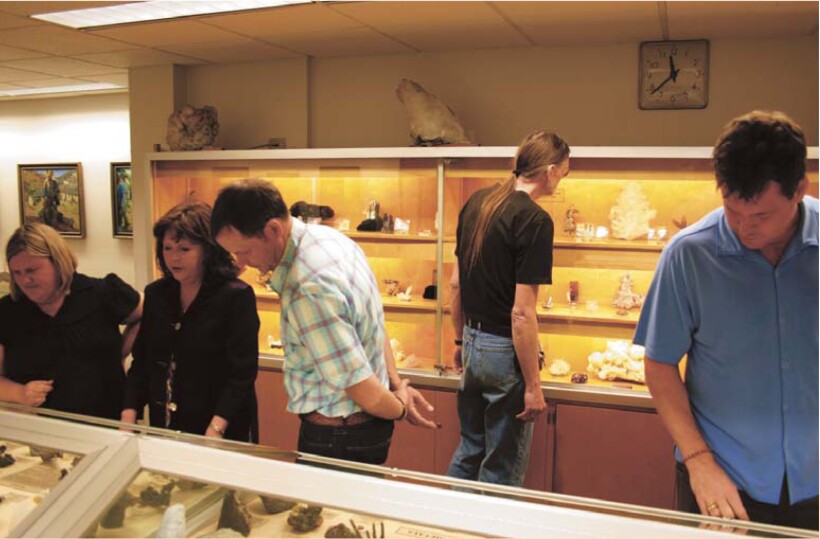

The mineral collection at the University of Arizona, which boasts 27 276 specimens and has been open to the public since 1892, was on the chopping block but will stay open thanks to a gift from a private donor.

SVEN BAILEY

The economy has scientists worried about both the health of their fields and the young scientists who may be forced to defect. With two job offers this season, John Johnson is one of the lucky ones.

ROBERT DEMPSEY PHOTOGRAPHY

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org