Giant telescope teams seek funding

DOI: 10.1063/1.2982114

Two US-led groups are planning 30-meter-class optical-IR telescopes, each with a price tag approaching $1 billion. Neither project has yet raised enough private money to cover the full cost, and both hope for public funding. But before getting on board, NSF wants to see what priority the astronomy community places on extremely large telescopes in the next astronomy and astrophysics decadal survey, which will be completed over the next 18 months or so.

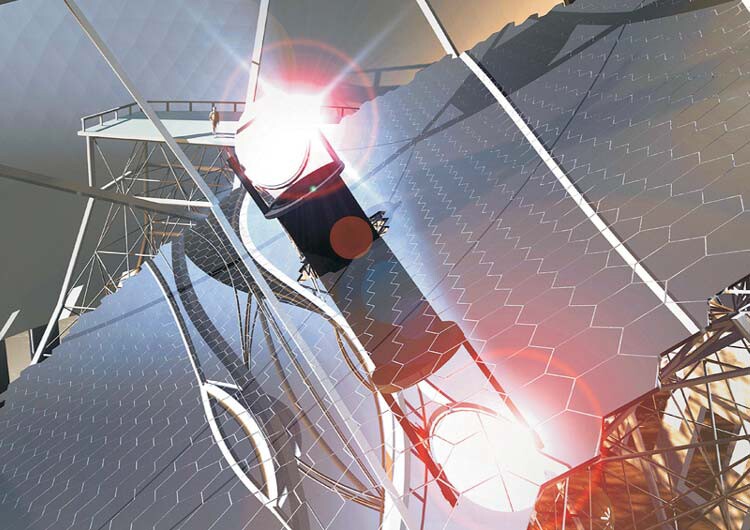

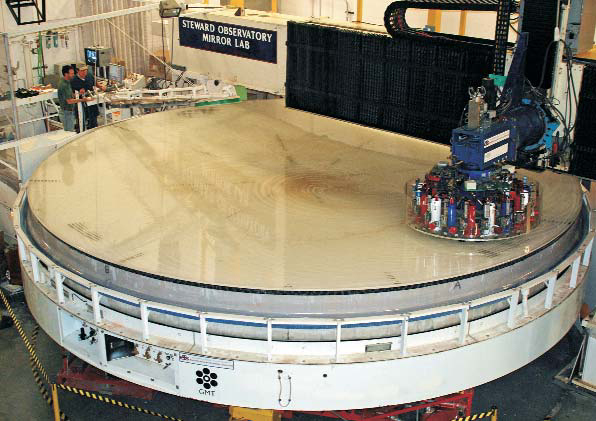

The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) design, an extension of the technology used in the Keck telescopes, consists of 492 1.4-meter hexagonal mirror tiles. The rival Giant Magellan Telescope’s (GMT’s) primary mirror would be made from seven 8.4-meter circular segments. It would have a diffraction aperture of 24.5 meters but, because of the gaps between the segments, a collecting area equivalent to a 22-meter telescope. “The two designs are sophisticated. It’s very likely that we will actually get to the diffraction limit,” says David Silva, director of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, which represents the broad astronomy community’s participation in the proposed telescopes. “The spatial resolution will be five times better than the James Webb Space Telescope [JWST], with roughly 20 times the photon collecting area.”

The exciting unknown

The science capabilities of the two telescopes would be similar, and their goals would include searching for extrasolar planetary systems and biomarkers, studying black hole growth and the formation of the earliest stars and galaxies, and probing dark energy and dark matter. “You start with problems you are stuck on with the facilities you already have and outline the case for a larger facility,” says Wendy Freedman, director of the observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the lead institution on the GMT. “But what’s likely to be most exciting is what we cannot even imagine now.”

The GMT has settled on a site in Las Campanas, Chile, while both the TMT and the 42-meter European Extremely Large Telescope have yet to choose between sites in the Southern and Northern Hemispheres—in Chile or Mauna Kea, Hawaii, for the TMT and in Chile, Argentina, the Canary Islands, or Morocco for the EELT. Some native Hawaiians oppose further development on Mauna Kea (see Physics Today, January 2004, page 22

Because the telescopes are independent, they could all end up in Chile. “It would be nice to have one in the North, but scientifically there is not much that demands it,” says Freedman. “The exception is nearer objects, and for some projects you want to cover the whole sky.” Some astronomers, however, are concerned about clustering the new facilities. “I think that’s a mistake,” says Bruce Carney of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who attended a June workshop on public participation in the giant telescopes. For example, he adds, the giant telescopes could coordinate with the JWST. “That’s an all-sky instrument, and it seems foolish to throw away a third or more of the sky. You become the myopic astronomer.”

Government participation?

For both the TMT and the GMT, going forward depends on amassing more money. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation has pledged $200 million to the TMT, on condition that UC and Caltech each raise an additional $50 million (see Physics Today, March 2008, page 20

A 50% share in an extremely large telescope was the top-ranked ground-based priority in the last US decadal survey. The US could get equivalent access through quarter shares in both the TMT and the GMT, but many astronomers doubt the US would spring for two. Indeed, they worry that participation in even one giant telescope may be out of reach. Others, though, note that before any 8- or 10-meter telescopes were built, many people believed only one was affordable; today there are a dozen.

“I do think it’s feasible [for the US government] to join both at the 25% level,” says Freedman. “There are many advantages to having two large telescopes.” And, with the EELT in the works, says the Carnegie Institution’s Patrick McCarthy, who heads the GMT’s science advisory committee, “If we want to maintain anything like parity—it will still be stretching to get that—both [the GMT and the TMT] projects need to succeed.”

But Carney cautions that a balance is needed between the new diffraction-limited telescopes and still serviceable smaller facilities. “There is not enough talk about better instruments for existing telescopes,” he says. At this point, says Wayne Van Citters, a senior adviser in NSF’s mathematics and physical sciences directorate, “NSF has to await the outcome of the decadal survey before making up its mind. We’ve told the community that many different paths might be possible.”

It’s not just for the money that the US-led teams want their government on board. “You can draw on the brain power of a much larger group of people,” says Silva. Adds Freedman, “It would be dreadful to go back to a time when telescopes are in the hands of a small group of private institutions and the general population doesn’t have access to them.”

The primary mirror of the Thirty Meter Telescope will be made from 492 hexagonal segments each 1.4 meters in diameter.

(The TMT image artist rendering is courtesy of the TMT Observatory Corp.)

The first of seven 8.4-meter mirror segments that will make up the Giant Magellan Telescope’s primary mirror is polished by a stressed lap, which deforms as it moves across the asymmetric surface called for in the telescope’s off-axis design.

JEFF KINGSLEY GMT

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org