Europe sets priorities in astroparticle physics

DOI: 10.1063/1.3027982

“If I was a young physicist today, I would be very excited. We are close to a third revolution concerning our knowledge about the universe.” So said Nobel physicist Carlo Rubbia in Brussels, Belgium, at the late September rollout of a road map for European astroparticle physics. Rubbia mentioned Copernicus displacing Earth from the center of the universe and Charles Darwin’s theories on evolution, and added, “We will be focused on the fundamental question: What are we made of? Ninety-five percent of matter and energy in the universe is largely unknown to scientists. Astroparticle physics will help in unveiling these secrets.”

The Astroparticle European Research Area (ASPERA) road map was made with the involvement of 19 funding agencies in 14 countries and sets the strategy for the field over the next decade. Crowning the list of priorities are seven projects to study dark matter, cosmic rays, neutrinos, and gravitational waves. The time frames for the projects are staggered to fit into a projected €1 billion ($1.4 billion) budget and, in some cases, to wait for results from current experiments before committing to the next step.

An independent astronomy road map by Astronet—like ASPERA, a coalition of European funding agencies—is broader and gives high marks to areas of overlap with ASPERA, namely, the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA) and KM3NeT, an underwater neutrino telescope. A draft Astronet road map was released in May with the final version due out this month (see Physics Today, April 2007, page 32

“In many fields we are moving with fantastic speed,” says ASPERA road-map chair Christian Spiering of DESY, the German Electron Synchrotron in Hamburg. “I am optimistic that, assuming the necessary funding, the next years will really open something new. A discovery on any of these fronts would open an entirely new field of research.”

Astroparticle wish list

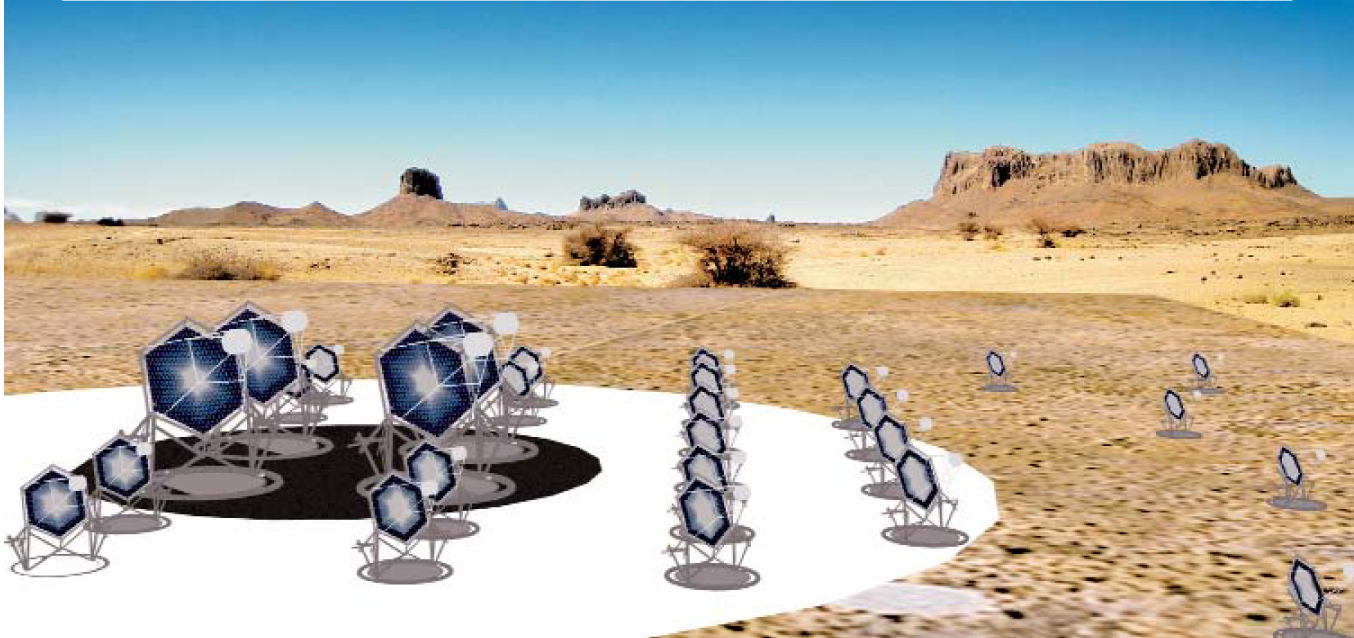

The CTA and KM3NeT are the most advanced projects on the ASPERA road map. With an estimated cost of €150 million, the CTA will have facilities in the northern and southern hemispheres to study galactic and extra-galactic gamma-ray sources. The €150 million-250 million KM3NeT will consist of thousands of detectors over at least a cubic kilometer in the Mediterranean Sea. It will watch for neutrinos from such sources as active galactic nuclei, supernovae, and gamma-ray bursters. Construction on those projects could begin in about four years.

For the CTA, says Spiering, “the technology is watertight. It’s a matter of making it cheaper and making it global—making it converge with the [proposed] American project AGIS [Advanced Gamma-ray Imaging System].” The CTA and KM3NeT are both on the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures road map, which looks across all science fields.

A third high-energy project endorsed by the ASPERA road map is the US-led cosmic-ray observatory Auger North. The road map suggests that Europe contribute about €45 million, roughly half the project’s total cost.

A second wave of projects will come from “a blooming of interesting and competing technologies on neutrino mass and dark matter,” says Stavros Katsanevas, ASPERA coordinator and a deputy director of IN2P3/CNRS, France’s national institute for nuclear and particle physics. Ton-scale detectors in those areas will cost €50 million–200 million, he adds. At present, notes Spiering, “this is a divergent field, with about 25 dark-matter experiments worldwide. They are now on the level of 10 kg; some are increasing to 100 kg. To increase the sensitivity, you have to increase the mass. We have to wait for the experiments that are presently starting before defining which method works best. We will define in 2010 or so which experiment should go first.”

A decision on the approach for a megaton detector to search for proton decay is expected in around four years. Rounding out the seven top priorities is an underground gravitational antenna. That would cost €300 million–500 million, says Katsanevas, and construction would start “only after [existing gravitational wave observatories] have seen a few sources—maybe in 2016 or 2017.”

The road map also recommends the creation of a European astroparticle physics theory center, possibly to be hosted by CERN. “Astroparticle experiments are widely spread all over the globe, often in rather inhospitable locales,” says Oxford University theorist Subir Sarkar, who served on the road-map committee. Theorists generally have interests broader than a given experiment, he adds, and “it is essential for us to interact face-to-face.”

Finally, the road map says that about a quarter of Europe’s astroparticle physics budget should go to existing smaller national projects, such as Europe’s participation in the US-led Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy, and Virgo, a gravitational-wave observatory.

Spreading the cost

“If we sum the astroparticle parts of the budgets” from all the relevant agencies, says Katsanevas, “we get €700 million over 10 years.” Projects on the ASPERA road map come to around €1 billion. “We showed this projection to the [funding] agencies, and we got a good reception. They looked with a good eye.”

“The other part in our strategy to keep all the road-map projects alive is by global coordination,” Katsanevas says. Through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, he adds, “we want to start a global discussion on world collaboration.” The OECD could take a census of existing strategies in different geographical regions and, says Katsanevas, “if we all agree, and I think we will, we will move to a concrete plan to collaborate.”

Dennis Kovar, the US Department of Energy’s associate director of high-energy physics, says, “The meeting [at which the road map was unveiled] was interesting because all of us see that the next generation of tools will require a lot of funding. You cannot duplicate capabilities. We need to regionally develop programs that complement programs elsewhere.”

The Cherenkov Telescope Array, which will have outposts in the northern and southern hemispheres, is one of the most advanced projects in Europe’s road map for astroparticle physics.

(Artist’s conception courtesy of ASPERA/Didier Rouable.)

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org