Convincing US states to require physics

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1163

“The big unpleasant surprise is that so few states are doing a good job,” says Paul Cottle, a physicist at Florida State University, referring to the readiness of high school graduates for college study in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). With Susan White of the Statistical Research Center at the American Institute of Physics (AIP), Cottle created the Science and Engineering Readiness Index.

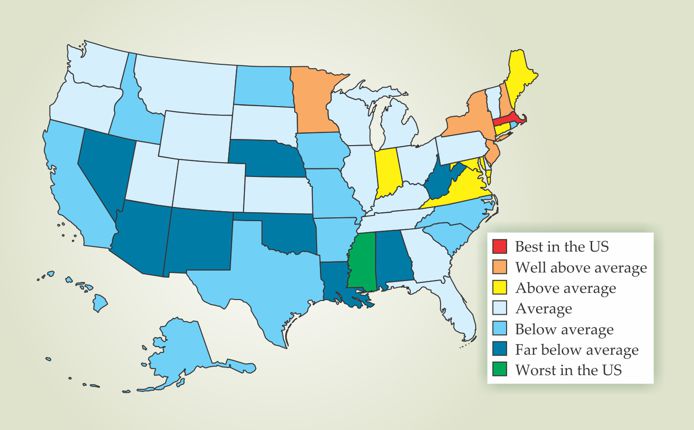

The SERI is based on information that is easily accessible online, including teacher-certification requirements and findings from Advanced Placement physics and calculus tests, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and surveys carried out by AIP. Massachusetts ranks highest by a long shot; Mississippi has the lowest ranking (see map, below).

A steady stream of international tests has shown that US high school students are performing below par in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. A new index shows state by state just how ill-prepared they are for university studies in those fields.

Data compiled by AIP Statistical Research Center

The SERI is different from other state-by-state comparisons because it is quantitative and focuses on physics, says Cottle. “When these sorts of analyses are done by outside organizations, they tend to focus on science as a whole, with an emphasis on biology.”

For example, Change the Equation, a national philanthropic coalition of businesses that aims to help K–12 STEM education, in April launched state “vital signs” reports. (See http://www.changetheequation.org/why/stem-education-in-your-state

“Having taken physics [in high school] is the strongest correlation to STEM degree attainment,” he says. Yet in 2008–09, according to the Florida Department of Education, 95% of the state’s high school students took biology, 70% took chemistry, and only 23% took quantitative physics. AIP data that include both conceptual and quantitative courses find a physics-taking rate for Florida high schoolers of 31%, compared with 37% nationally.

“In Massachusetts, they don’t push physics, students just take it. That’s how it should be. In the Southeast—which is weak in physics taking—we are attempting to make a cultural change.” That, Cottle says, is why it’s important to understand the national picture: “We have to be able to compete with Massachusetts. [Then] the question is whether Massachusetts can keep up” with the likes of high-performing countries Singapore and Finland.

Cottle got involved in ranking states after working on science standards for Florida only to be disappointed that recommendations for physics requirements were ignored. Later, however, his state’s department of education increased the requirement for high school graduation to include either physics or chemistry, starting with the class of 2017. He hopes the SERI helps get the word out and leads to change, but admits that “it’s very tough to sell physics to school districts.” Still, that’s his goal: “I would like to see the best students from our high schools—the ones who are headed to universities—be STEM-ready. That is where the best economic opportunities are.”

For the full SERI report, see this summer’s issue of the American Physical Society Forum on Education newsletter, http://www.aps.org/units/fed/newsletters/index.cfm

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org