Climate change research cut as Canada focuses on mitigation

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3689

Under its present government, Canada makes no secret about aspiring to be a world leader in coping with climate change. The country punches above its weight in international climate policy discussions. It’s a signatory to the Paris climate accord. And one of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s early actions after he took office last year was to add “climate change” to the name of what’s now the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) department.

So it’s no wonder that the country’s climate scientists were surprised and dismayed when funding for large-scale research networks in their field was not included in the 2017 federal budget released in March. The five-year, Can$35 million ($28 million) Climate Change and Atmospheric Research (CCAR) program expires at the end of this year, and the new budget does not provide for its continuation or replacement. At stake are facilities in the Arctic, data continuity, collaborations between academic and government scientists, and recruitment into the field.

Floods soaked downtown Calgary, Alberta, on 21 June 2013. Scientists in Canada’s Climate Change and Atmospheric Research networks use computer simulations to estimate the anthropogenic contributions to such extreme weather events.

RYAN QUAN

“There is an unfortunate perception that no more science is needed in climate research,” says Paul Kushner, a University of Toronto physicist and principal investigator of a CCAR project on observations and predictions of sea ice and snow. The Canadian government is prioritizing mitigation and clean technologies, he says.

In the budget, the government lays out its plans to invest Can$22 billion over 11 years in green infrastructure. Among many other areas, that money will go toward commercialization of emerging renewable technologies; developments that foster clean air, soil, and water; development and implementation of building codes; and disaster mitigation.

“Those things are important,” says Kushner, “but we need state-of-the-art observations and models to assess the role of climate change in major floods, wildfires, droughts, sea-ice loss, and other climate extremes. We need to invest in climate science research to keep up with rapid environmental and technological change.” The science is crucial to advise on policy and response strategies, he adds. “It seems like we are falling through the cracks.”

Yet even if, as Kushner and many of his colleagues believe, the disruption in funding for climate science is more of an oversight than a considered decision, the message to the world is damaging, says Rémi Quirion, Quebec’s chief scientist. “The feeling from the global community is that Canada doesn’t care anymore. We will have to work on that.”

“You have to be there”

The CCAR program funded seven projects that support government priorities related to weather and climate. The projects involve measurements, observations, and modeling in the following areas: aerosols and their impacts; biogeochemical tracers in the Arctic Ocean; sea ice and snow cover; weather prediction and climate projection; changes to land, water, and climate; exchange of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and heat between the ocean and atmosphere; and the temperature and other properties of the atmosphere in the high Arctic. The networks that carry out the projects are made up of scientists from academia and from the ECCC, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and other government bodies. Some also have international partners and members from nonprofit organizations and industry.

The seven projects each received roughly Can$1 million annually. The money is used to pay students and technicians, and for fieldwork, travel, equipment, and infrastructure maintenance. Much of it has gone to train upward of 350 students and postdocs, according to Kushner.

The Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory, a Canadian research facility in the high Arctic, will have to go into suspended animation unless money materializes to keep it open. Here, scientists are adjusting a dome that protects a spectrometer used to measure atmospheric ozone and related gases.

DAN WEAVER

Laxmi Sushama, who in August moved to McGill University from the University of Quebec in Montreal, leads a CCAR network that aims to quantify and reduce uncertainties in weather prediction and climate projection for Canada’s northern regions. “The CCAR networks demonstrated the benefits of collaborative multi-institutional weather and climate research,” she says. For example, she and her colleagues have incorporated permafrost, changing vegetation, and glacier dynamics into computational models to represent land–atmosphere interactions and improve simulations of the regional hydrology and climate. And they have used their models to assess how anthropogenic emissions alter the likelihood of floods, heat waves, wildfires, and other extreme weather events.

When Sushama heard that CCAR would not be renewed, she began looking for other sources of funding. Her research will continue, she says, “but the pace of weather and climate research in academia may slow down.”

Projects involving ships, brick-and-mortar facilities, and major instrumentation in the Arctic are most at risk by the discontinuation of CCAR. “There are few places where you can make measurements in the high Arctic year-round,” says James Drummond, principal investigator for the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory (PEARL) on Ellesmere Island, whose Cape Columbia is Canada’s most northerly point. “We are right underneath the ozone-depletion region. We have looked particularly at the polar night. There are some very interesting things going on that we are trying to understand.” And he notes that if something happens, “you can’t say, ‘Let’s go study it!’ You have to be there already.”

Among other measurements, the PEARL team does surface sampling of aerosols and uses sunlight for spectroscopic studies of atmospheric composition—tracking the transport of pollutants into the Arctic, detecting greenhouse gases, and measuring chemicals associated with ozone chemistry. PEARL data are also used to validate satellite measurements.

Dusting off shut-down plans

It’s not the first time that Canada’s climate-research community has faced funding uncertainties. CCAR was created in 2011 as a one-off after the federal government ended its better-endowed predecessor, the Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences (CFCAS). With funding beginning in 2013, CCAR came at the eleventh hour for PEARL, which had been on the verge of closing (see Physics Today, July 2012, page 20

A key aim of the CFCAS and then CCAR has been to promote collaboration between scientists in academia and in government. Bill Merryfield, a scientist at the ECCC’s Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis in Victoria, British Columbia, says that those initiatives “really gave a boost in my area.” For example, he and his colleagues introduced new ways to capture carbon-cycling pathways and feedbacks. Their models, he says, “are now applied in official seasonal forecasts and experimental climate predictions out to a decade.”

Marjorie Shepherd, who heads the climate research division at the ECCC, agrees that a strong collaborative relationship with academia is “very important for achieving the full breadth of research.” About the end of CCAR, she says, “We have been through transitions before. Opportunities change and evolve. We do expect to continue collaborative research with the academic community.”

To that end, Shepherd points to a white paper released in June by the academic–government partnerships committee of the ad hoc working group Atmosphere-Related Research in Canadian Universities. It identifies areas for cooperation in atmospheric, weather, and climate research. But Kushner, who is the lead author on the paper, says it has no teeth and no money: “It’s a dialog, an organizational effort in our community.” He hopes it will lead to a community-wide effort in long-term strategic planning and priority setting—along the lines of the exercises that, for example, US astronomers, planetary scientists, and high-energy physicists undertake roughly every decade.

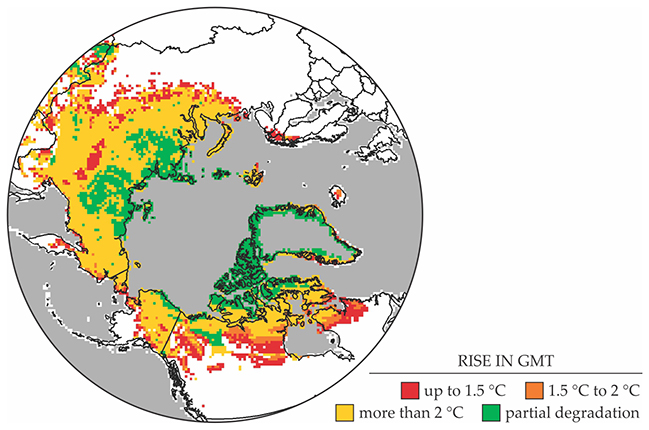

Pan-Arctic Regional Climate Model projections of disappearing permafrost, as a function of the rise in global mean temperature (GMT). The map shows regions of total (red, orange, yellow) and partial (green) permafrost degradation in the upper 3 meters of soil, for a high-emissions scenario. (Adapted from Bernardo Teufel and Laxmi Sushama, Canadian Network for Regional Climate and Weather Processes.)

Uncertainty

A spokesperson for the office of Canada’s minister of science says, “Our government is taking a comprehensive approach to addressing climate change, including investing in climate research across government.” She adds that with CCAR ending, the program’s parent agency, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), “is working with researchers to find other potential avenues of support,” including through competitive grants totaling roughly Can$50 million a year.

But Kushner notes that NSERC grants are typically too small to take on large-scale nationally coordinated climate research and that other sources of money currently available from the federal government are also inadequate. “CCAR was the premiere climate research program offered by the federal government. It hasn’t been replaced by anything currently on the table, and this is unfortunate,” he says.

“We are not asking for the existing individual networks to be renewed,” says Kushner. “We want a new call for a peer-reviewed process.”

For now, climate researchers still face uncertainty. “There is turmoil in transition,” says Gordon McBean, who headed the CFCAS. People lose jobs, they leave the field, students get left in limbo, and laboratories fold, he notes. “You can’t just turn off and on science of this kind. The big question is, What do we do now?”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org