Antarctic ice shelves are prone to slush

DOI: 10.1063/pt.uvhq.trps

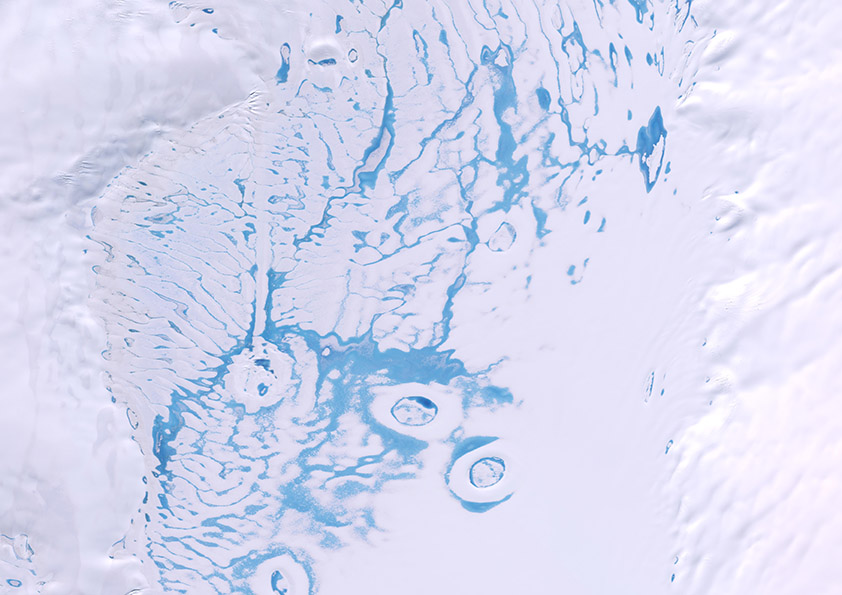

Meltwater slush and lakes are shown covering a portion of the surface of Antarctica’s Bach Ice Shelf in a satellite photo last year. Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2023), processed by Rebecca Dell

More than a tenth of Antarctica’s surface overhangs the ocean. The continent’s floating ice shelves preserve flowing glacial ice that would otherwise slip into the Southern Ocean and cause global sea levels to rise. Without the benefit of underlying bedrock, however, ice shelves are vulnerable to weakening and even calving when liquid water seeps through them (see the Quick Study by Kristin Poinar, Physics Today, October 2023, page 70

The Larsen B event underscores the importance of tracking ice shelf meltwater, particularly as the poles warm faster than the rest of the planet (see the article by Sammie Buzzard, Physics Today, January 2022, page 28

After training their algorithm

The measured meltwater abundance has implications for the future of Antarctica’s ice shelves. Whether originating in ponds or as slush, liquid water percolates into the firn, the porous boundary layer that buffers a shelf’s deep, compressed ice from its snowy surface, and can exacerbate fractures in the ice. Meltwater also causes problems when it resolidifies: Freezing water releases latent heat, which warms the surrounding snow and ice, and then forms less permeable ice that promotes the ponding of future meltwater.

Slush is also darker than pure snow, so it absorbs more sunlight. Dell and colleagues measured the albedo values for the waterlogged regions of five ice shelves and compared them with estimates derived from a leading polar climate model. The researchers found that the model overestimated the surface reflectance for both lake-filled and slushy regions and thus underestimated how much those surfaces would melt. Correcting models and further improving meltwater detection should improve researchers’ predictions of how Antarctic ice shelves will fare as global temperatures continue to rise. (R. L. Dell et al., Nat. Geosci., 17, 624, 2024, doi:10.1038/s41561-024-01466-6

This article was originally published online on 11 July 2024.

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org