Demands on early-career faculty

DOI: 10.1063/pt.uplj.znns

I very much enjoyed Alex Lopatka’s article “Early-career faculty face many challenges

I have been blessed to have a career spent in positions in colleges and universities that have a primary emphasis on teaching and a lower level of research expectation. In 29 years as a professor, my lightest teaching load for any semester was eight hours, and that was during my first year in a tenure-track position. I had that “reduced” teaching load because I was also serving a one-year term as the interim chair of the department. Last semester, my teaching load was 11 hours. And I have done all of the grading in all of my courses—I’ve never had a graduate teaching assistant.

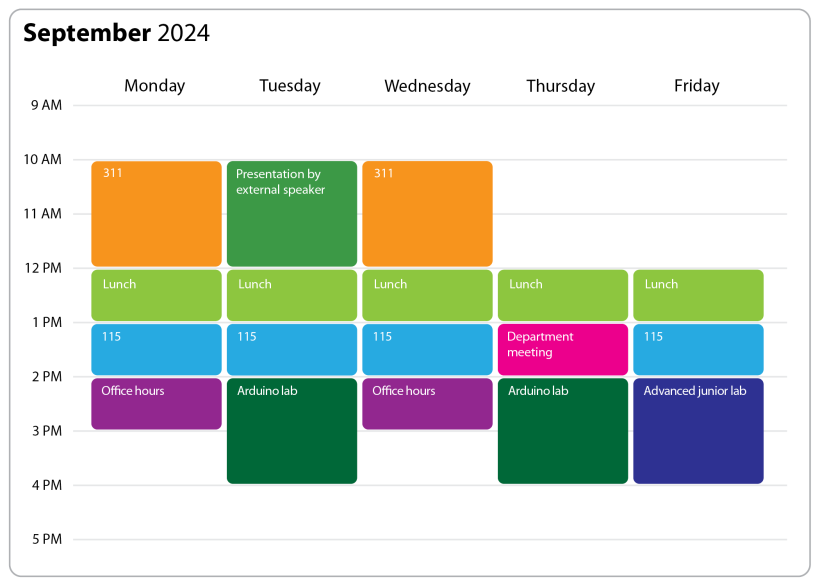

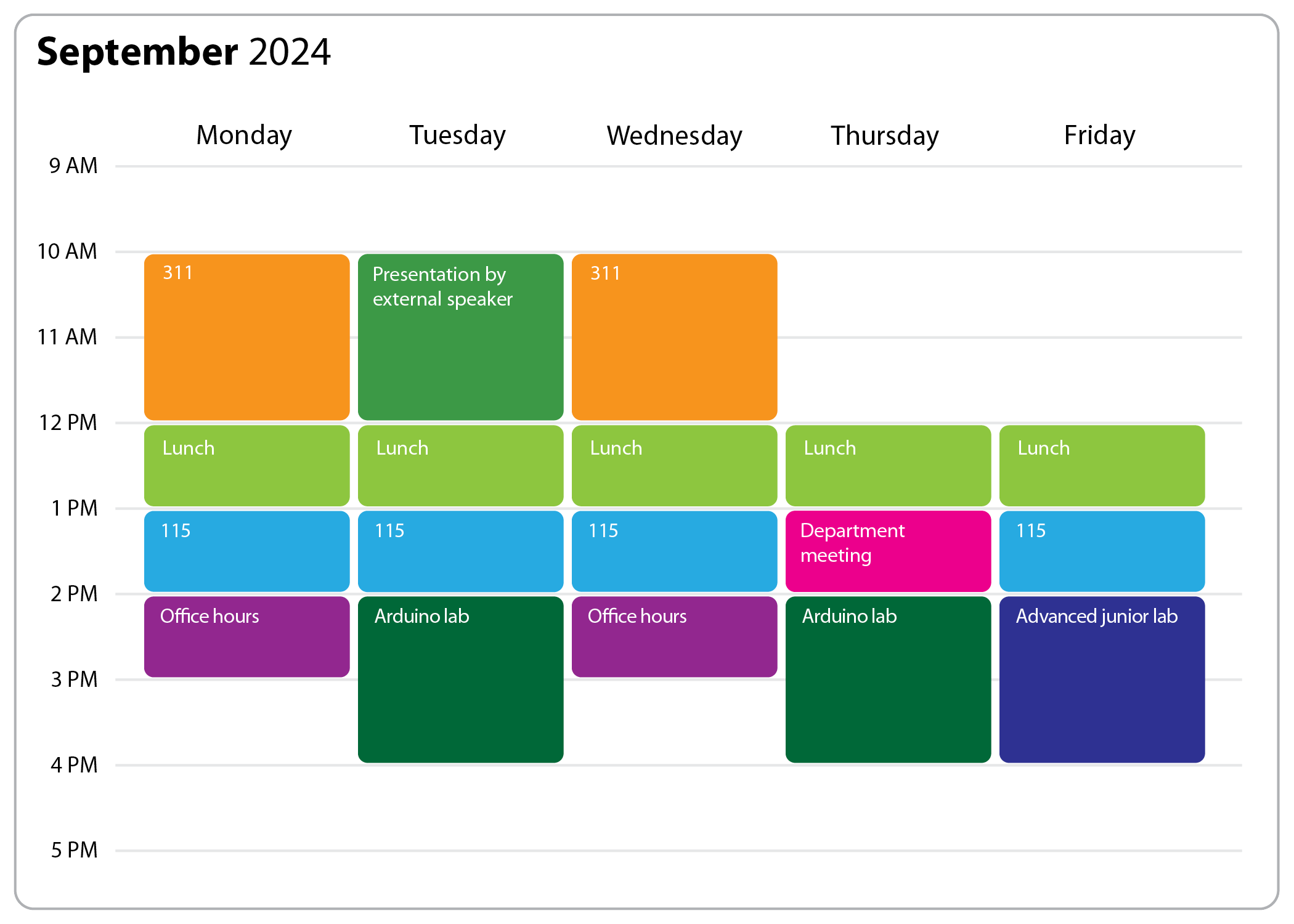

The author’s schedule last semester. (Illustration by Freddie Pagani.)

That isn’t to say the research component of the job is easy. There are about 2600 four-year degree-granting postsecondary institutions in the US, but only about 150 of those are classified as R1 institutions (doctoral universities with “very high research activity”) by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. The academic positions at non-R1 schools, which make up the majority, will have reduced research expectations compared with academic positions at R1s, but they are still stringent. Such expectations include publishing at a certain rate and obtaining external funding.

To do the latter, you must convince an agency to fund projects that are based on research you have done—which may not be much if you have a high teaching load—using the equipment you hopefully already have. Keep in mind that if you aren’t at an R1, your startup package as an experimentalist will not be $1 million, as is described on page 42 (again, I laughed out loud). A startup package of $40 000 would be much more typical. In my department, in order to have a successful grant application for any major equipment, my colleagues have needed to describe to the agencies how that equipment will be used in upper-level courses. In my experience, research gets done half as fast with undergraduates helping and twice as fast with graduate students helping—and the funding agencies know this too. Undergraduates might be on your team for only three years or less, so you’ll be constantly building a new team of members with diverse academic backgrounds.

I am not writing because I am jealous of the hypothetical teaching schedule shown, and I am aware of the greater research requirements imposed on faculty at large PhD-granting universities. I have had my schedule because I love teaching and doing research with undergraduates. I definitely do not want to trade places with someone with the schedule on page 43, which is hopefully someone who loves doing research and interacting with graduate students. I hope that I have been preparing my students sufficiently so that you enjoy working with them as graduate students as much as I have loved working with them all these years. I am just suggesting that it would have been helpful to include a second, alternate version of the teaching schedule for an academic position in physics.

More about the authors

Joseph O. West, (joseph.west@indstate.edu) Indiana State University, Terre Haute.