Biological eigenstrokes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3505

On their way to becoming mature, bottom-dwelling adults, many marine invertebrates, including starfish, first go through a larval stage that’s covered in bands of densely packed, beating cilia. As they are carried along by currents, the larvae rely on the ciliary bands both for locomotion and for entraining phytoplankton on which they feed.

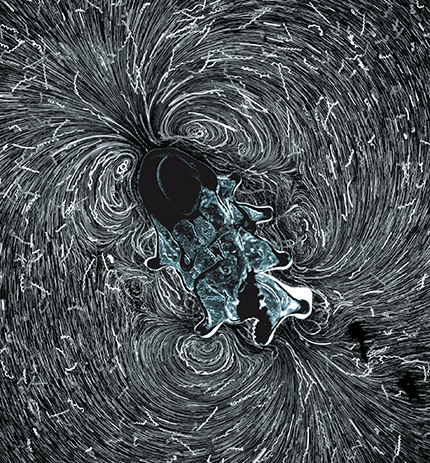

Biological eigenstrokes - Image submitted by William Gilpin.

William Gilpin, Vivek Prakash, and Manu Prakash at Stanford University have used a combination of live imaging and mathematical modeling to study the hydrodynamical flows produced by larvae of the common starfish Patiria miniata. This long-exposure photo captures a 1-mm-long larva confined between a microscope slide and a coverslip. Microbeads and algae in the water reveal the complex pattern of vortices and antivortices generated by the beating cilia. The pattern evolves slowly over time as the larva reverses the beating direction in localized regions of the ciliary bands.

The researchers find that the larvae exhibit distinct “eigenstrokes”—one for swimming and one for feeding, the latter characterized by larger numbers of vortices and of domain walls along the ciliary bands that resemble topological defects. (W. Gilpin, V. N. Prakash, M. Prakash, Nat. Phys., in press, doi:10.1038/nphys3981. Image submitted by William Gilpin.)

To submit candidate images for Back Scatter visit http://contact.physicstoday.org