Condensed-matter titan

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4858

What do theoretical physicists actually do? George Gamow once joked that theorizing was outwardly indistinguishable from napping. As the physicist and historian David Kaiser noted in his 2005 article “Physics and Feynman’s diagrams,” Gamow’s joke implies that historians of theoretical physics face a difficult challenge. How do you describe what’s happening while a theorist stares at a screen or out the window (or at the backs of their eyelids!) for hours at a time? Gamow was fond of hyperbole, of course, and many elements of theorists’ practice are in fact amenable to description, but the joke does point at a real conundrum.

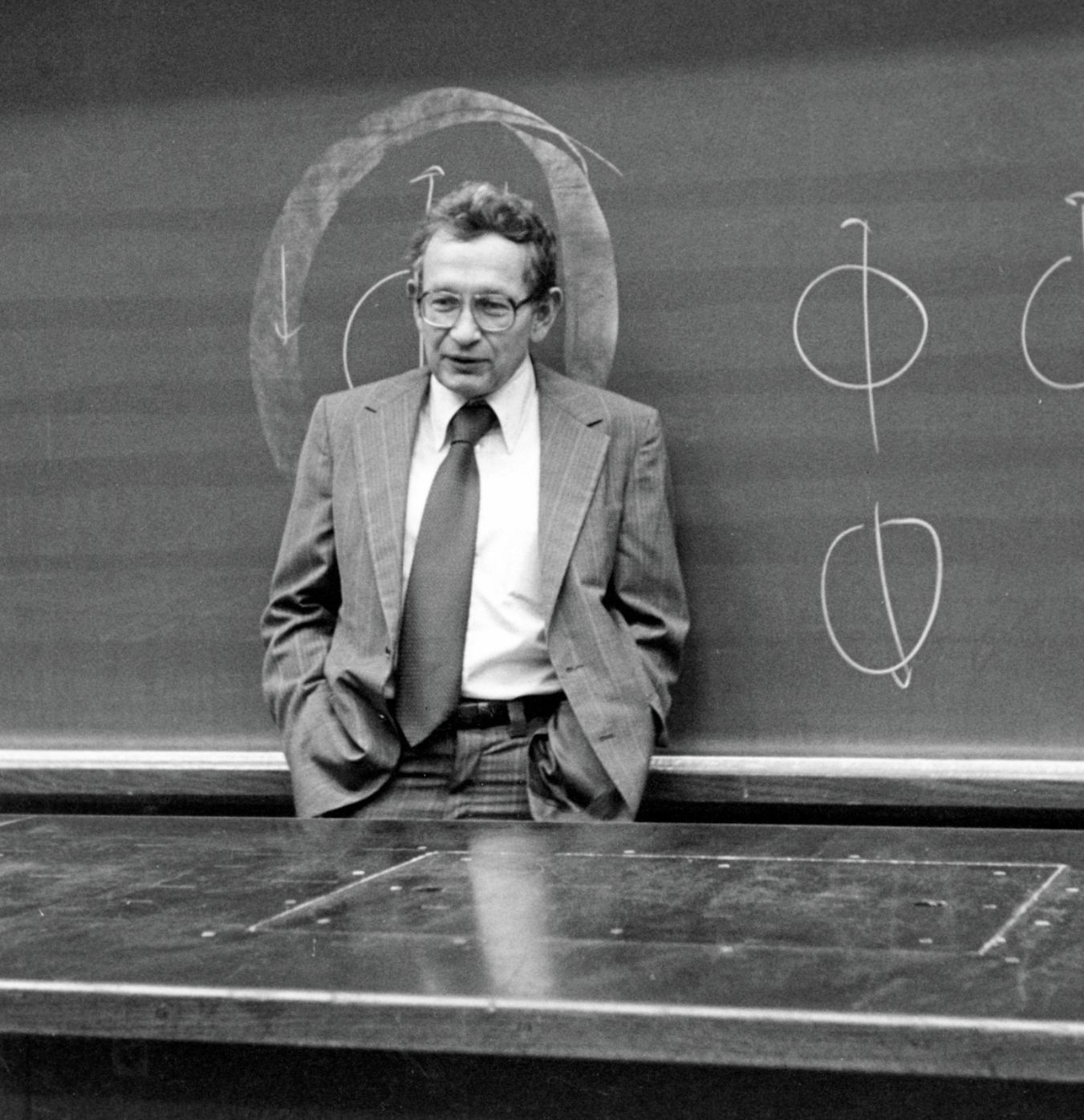

Philip Anderson lecturing in front of a blackboard.

AIP ESVA, SEGRÈ COLLECTION

At least with respect to the practice of one influential theorist, the Nobel laureate and primus inter pares of condensed-matter theory, Philip Anderson, Andrew Zangwill attempts to answer Kaiser’s question. Zangwill is both a theorist and historian of condensed-matter physics, so his lucid descriptions of Anderson’s enormous contributions in A Mind Over Matter: Philip Anderson and the Physics of the Very Many are backed by a deep understanding of both the ideas and the community in which those ideas found a home. But he isn’t satisfied with just explaining the ideas—he wants to show readers how Anderson arrived at those ideas and give them a sense of his practice and personal style as a theorist.

Zangwill largely succeeds in that aim, although he acknowledges that some aspects of Anderson’s creative process—and it was very much a creative process—will always remain a mystery. In fact, they were a mystery to Anderson himself. A Mind Over Matter demonstrates that Anderson, more than many of his peers and competitors, enjoyed hanging out with experimentalists and perusing experimental data; that he generally sought out problems where he could make a first, dazzling contribution and then move on to other topics; that he preferred to leave the number crunching to others and intensely disliked theories and theorists that relied on digital methods; and that his best ideas (and the ones he valued most in others) could be exported to other physical fields and scientific disciplines.

Somewhat more speculatively, Zangwill argues that Anderson needed conflict to refine his physical understanding. That characteristic helps to explain both his combative relationship with other theorists and the failure of his late-career theory of high-temperature superconductors: By that point, Anderson was no longer surrounded by people willing to push back against him.

As the high-Tc story indicates, A Mind Over Matter is no hagiography. Zangwill treats Anderson with some reverence but isn’t afraid to confront his prickly, stubborn, and sometimes egocentric tendencies. Anderson comes across as a complicated, human, but nevertheless admirable character: He could be aggressive, dismissive, and petty toward those he viewed as competitors, but he was also supportive of the underdog both in his private relationships and his public politics. Zangwill also shows that Anderson’s contrariness often led him to some of his best decisions, such as opposing McCarthyism, choosing condensed matter as his specialty, and taking a job at Bell Labs instead of at a university.

Because of Anderson’s influence and wide network of collaborators and antagonists—who were sometimes one and the same—A Mind Over Matter is a biography of both his life and times. Along the way we meet the likes of Brian Josephson, Nevill Mott, William Shockley, Edward Teller, Murray Gell-Mann, and more. We also get an excellent peek at the rituals of postwar physics through the lens of Anderson’s critiques of the field. For instance, Zangwill offers some fine examples of Anderson’s prickliness as a peer reviewer and his short-lived attempt in the mid 1960s to run an alternative journal sans peer review. Although that experiment was not a representative portrait of midcentury journal practices, it nevertheless says a lot about the function and dysfunction of physics journals.

Given that I am a historian of industrial physics, my one disappointment with A Mind Over Matter is that the reader doesn’t get much of a sense of Bell Labs, the organization where Anderson worked for some 35 years. At that time, Bell Labs was the leading institution in condensed-matter physics and a host of other fields. But Zangwill doesn’t really show us what Anderson did as a manager in that organization. Maybe that’s because “What do middle managers do?” is an even harder question to answer than “What do theorists do?”

But Bell Labs’ curious marginalization in Zangwill’s account is a relatively minor blemish on an engaging and insightful biography. For anyone interested in Anderson’s contributions, his personal philosophy and style of physics, the fights he picked (for better and worse), and the scientific times in which he lived, A Mind Over Matter is an enlightening read.

More about the authors

Cyrus Mody is the professor of history of science, technology, and innovation at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. His research focuses on the history of the applied physical sciences in the US since 1965.

Cyrus C. M. Mody, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands.