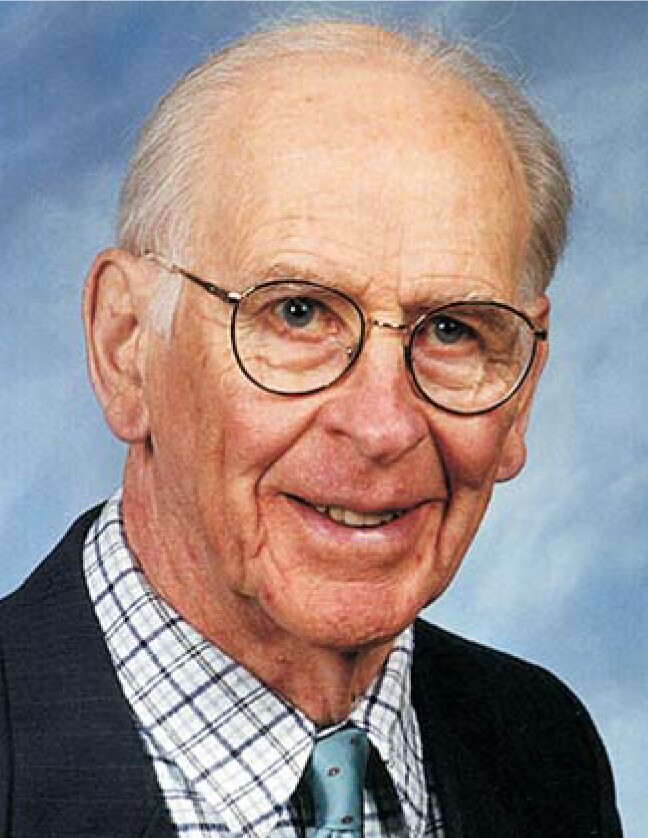

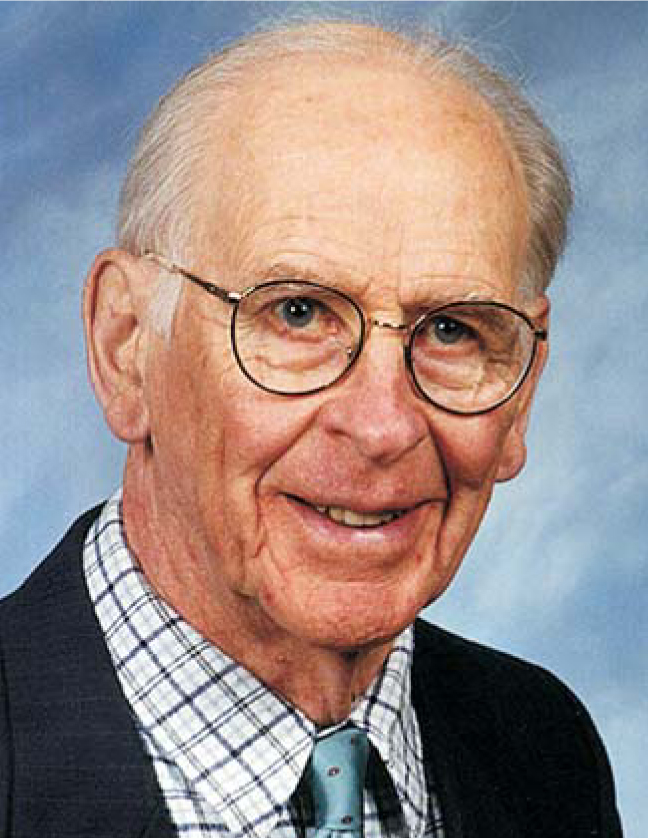

William Conyers Herring

DOI: 10.1063/1.3273023

William Conyers Herring passed away at his home in Palo Alto, California, on 23 July 2009 at the age of 94. He had suffered a heart attack in the early 1980s but remained active until recently. His influential contributions cover a wide range of condensed-matter physics, including the electronic structure of metals and semiconductors and thermodynamic, magnetic, and mechanical phenomena.

Born on 15 November 1914 in Scotia, New York, Conyers grew up in Parsons, Kansas, where he started school in the fifth grade at the age of five. At age 14 he entered the University of Kansas. He completed his bachelor’s degree in astronomy there in 1933, then spent a year studying at Caltech. He transferred to Princeton University because it had fewer required courses, and he greatly valued having free time to study independently. Conyers switched his focus from astrophysics to solid-state physics, and he and thesis adviser Eugene Wigner, along with fellow graduate students John Bardeen and Frederick Seitz, created the modern band theory of solids. His thesis, “On Energy Coincidences in the Theory of Brillouin Zones,” was completed in 1937. For the next two years Conyers was a National Research Council fellow at MIT, where he developed the orthogonalized planewave method, the first workable scheme for calculating the electronic energy bands in solids; the scheme was subsequently used by Frank Herman at RCA to make the first realistic band-structure calculations of germanium and silicon.

After having taught physics at the University of Missouri from 1940 to 1941, Conyers served as a member of the division of war research at Columbia University during World War II. In 1946, after a short professorship in applied mathematics at the University of Texas, he was invited to Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, by William Shockley, who was impressed with his war work.

At Bell Labs, Conyers created the theoretical physics department, which for years was the world premier group in what was then known as solid-state physics. He organized a journal club that met weekly, in which he or local experts critically reviewed what he deemed to be significant results from the literature. Meanwhile, solid-state physics was expanding to represent more than half of all physics. At a special journal club meeting, held in honor of his 80th birthday, Walter Kohn spoke for himself and many others when he described Conyers as “the wise old man, to whom we all went for advice and information.” His famous catalog of thousands of three-by-five cards, which he kept in a black suitcase, contained references and terse critical comments compiled from long hours in the library. To include ongoing important work from Russia, for which publications were unavailable in English during the cold war, Conyers simply learned Russian. With those cards he served as a one-man Google—actually more useful, because he had already filtered out the extraneous material. Wigner remarked to one of us (Geballe) that whenever he wanted to know something in solid-state physics, Conyers was his first resource.

Conyers was known not only for his knowledge but for his considerate way of sharing it, treating everybody with respect and quietly providing keen insights. His constructive suggestions often made it easy to identify him when he refereed papers. Albert Overhauser referred to him as the “patron saint of referees.”

The range of his individual contributions was remarkable. His review of exchange among itinerant electrons, which started as a chapter but turned into a book on magnetism, was one of the first texts to recognize the role of collective excitations in metals. In reviewing the book (Physics Today, April 1967, page 75

Conyers predicted in 1951 that what are now known as nanorods should have a much greater range of elastic strain than bulk material because they would either be free of dislocations or have too few to generate observable slip. That prediction was soon verified by experiments he did with John Galt that demonstrated the enormous strength of tin microwhiskers.

Because Bell Labs had a compulsory retirement age of 65, Conyers moved to Stanford University as a professor of applied physics in 1978; he continued to be active until the past few years. A great resource to students in preparing theses and in asking penetrating questions, he also gave a series of lectures on the history of solid-state physics as part of Stanford’s centennial celebration. With colleagues at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, where he was a consultant, he jointly published papers on unexpected properties of hydrogen in silicon.

His many honors include the 1959 Oliver E. Buckley Condensed Matter Prize of the American Physical Society; the Von Hippel Award of the Materials Research Society and the National Academy of Sciences’ James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing, both presented in 1980; and the 1984–85 Wolf Prize.

Conyers had many outside interests. Having a deep, nonjudgmental faith in Jesus Christ, he was a lecturer, with nine others, of a science-and-religion series at Stanford in 1985. He thought that theology underlies science because “science is ultimately based on leaps of intuition and aesthetic perceptions.” He was an avid tennis player and a wit who could produce a clever limerick almost spontaneously. His contributions to physics will live. Those who knew him will cherish memories of this remarkable man.

William Conyers Herring

STANFORD UNIVERSITY

More about the authors

Phil Anderson, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, US.

Ted Geballe, Stanford University, Stanford, California, US.

Walt Harrison, Stanford University, Stanford, California, US.