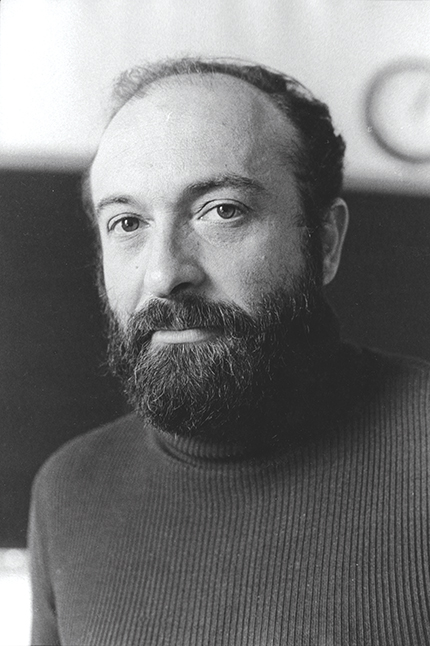

Peter George Oliver Freund

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4171

On 6 March 2018, Peter George Oliver Freund—prominent theoretical physicist, fiction writer, lover of the arts, and raconteur—died in Chicago at age 81.

Peter was born on 7 September 1936 in Timișoara, Romania, into a well-off and cultured Jewish family. His father was a doctor and his mother an opera singer. His early life was disrupted first by the Nazis and then by Soviet rule. His family fled Romania for Israel in 1959. After a last-minute dramatic visa appeal, Peter was able to enter the doctoral program at the University of Vienna, where he received his PhD in particle physics in 1960 under the supervision of Walter Thirring.

The early 1960s were a busy time for Peter. In 1961 he was appointed as a research associate for theoretical physics at the University of Vienna. Later that year he received an appointment as chef de travaux at the University of Geneva’s Institute of Theoretical Physics. He moved to the University of Chicago as a research associate in the fall of 1962 and was appointed to the Chicago faculty in 1965.

Peter George Oliver Freund

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Peter entered particle physics during the early days of Regge-pole phenomenology. He wrote numerous papers that helped develop both the formalism of finite-energy sum rules and the ideas of dual-resonance models that were the precursors of string theory. His studies on magnetic monopoles, the topology of gauge fields, and the function of the axial anomaly in gravitational theories were critical to understanding the role of topology in particle physics. Peter loved novel mathematical structures and early on appreciated the possible role of supersymmetry in particle physics; not long after the discovery of spacetime supersymmetry, he and Irving Kaplansky wrote a paper on the classification of graded Lie algebras.

Peter’s most cited paper, written with Mark Rubin in 1980, is on the dynamics of dimensional reduction in higher-dimension theories in which gravity interacts with antisymmetric tensor gauge fields. That situation arises in many supergravity theories and has been critical in the anti–de Sitter/conformal field theory correspondence. In the 1980s Peter wrote a series of papers with Lee Brekke, Mark Olson, and Edward Witten on the possibility of using p-adic numbers to define a new kind of string theory. It seems fair to say that their work led to striking results that, if they are to be fully incorporated into the theory’s structure, will require new ideas. Following the work of Michael Green and John Schwarz on anomaly cancellation, Peter wrote a note that anticipated some of the structure of the heterotic string.

Many physicists know Peter not only for his research but for his remarkable storytelling ability. He viewed physics as a very human enterprise, embedded in the culture of the times, with ties to the arts and influenced by the prevailing intellectual winds. He told rich and elaborate stories, continually adding to them and perfecting his delivery. Those stories included the many colorful adventures of his family and of the numerous physicists and mathematicians he admired. Several of his tales are collected in his book A Passion for Discovery (reviewed in Physics Today, August 2008, page 56

His passion for physics and storytelling made Peter a compelling teacher who motivated many generations of students at the University of Chicago. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Frank Wilczek said, “I’d especially like to mention the inspiring influence of Peter Freund, whose tremendous enthusiasm and clarity in teaching a course on group theory in physics was a major influence in nudging me from pure mathematics toward physics.”

Peter was a romantic at heart, with an aristocratic bearing, a booming baritone voice, and a highly developed aesthetic sense. He had a lifelong love of opera and sang in an amateur opera company in Chicago. With his passing, we have lost a stimulating colleague, an engaging teacher, and a dear friend.

More about the authors

Jeffrey A. Harvey, Enrico Fermi Institute, Chicago, Illinois.

Emil J. Martinec, Enrico Fermi Institute, Chicago, Illinois.