Michael Francis A’Hearn

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3824

Michael Francis A’Hearn, Distinguished University Professor Emeritus at the University of Maryland, died on 29 May 2017 at his home in University Park, Maryland, after a short battle with pancreatic cancer. He was a pioneer in planetary astronomy, particularly in the nature and chemistry of comets and their relationship to the cosmogony of the solar system.

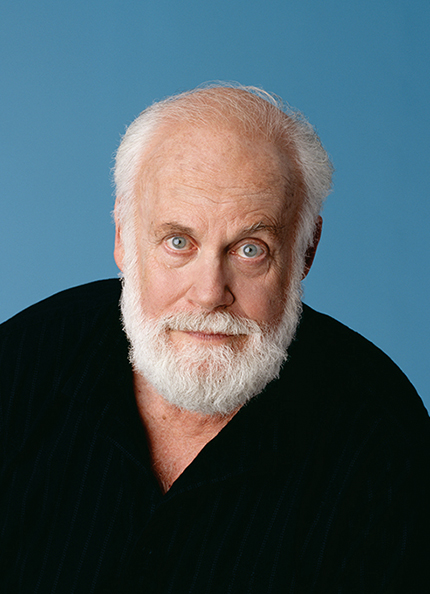

Michael Francis A’Hearn

RHODA BAER

Born on 17 November 1940 in Wilmington, Delaware, and raised in Boston and Washington, DC, Mike earned his BS in physics from Boston College in 1961. He received his PhD in 1966, with a thesis on the polarization of the atmosphere of Venus, under the direction of Arthur Code at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Mike was then hired as a faculty member at the University of Maryland, where he spent his academic career primarily studying solar-system phenomena.

A quote from Mike’s last paper, published online at the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A on the day of his passing, perhaps best describes his scientific focus: “We outline the key questions about comets that must be answered in order to understand cometary formation in the context of the protoplanetary disc and the role of comets in the formation and evolution of the solar system.” Mike came into the cometary-science field when the detailed structure and composition of comets was just being formulated and debated; models, derived from ground-based optical photographic-plate data, ranged from flying sandbanks to discrete kilometer-sized nuclei. His work, which progressed from ground-based telescopic measurements using the first CCDs and single-element bolometers to cometary in situ spacecraft observations (now totaling five close flybys and one comet rendezvous), helped show that comets are consolidated, primitive, loosely packed icy mud balls from the dawn of the solar system and building blocks of the planets.

Mike is perhaps best known scientifically for helping to discover the presence of water ice and diatomic sulfur emission in cometary comae, introducing the Afρ geometry-independent measure of coma dust density, determining the rotation rates of comets by observing their cyanogen jets, and resolving the dark, low-albedo nature of cometary nuclei. He used the Lowell Observatory’s compositional survey of 85 comets from the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud to search for chemical gradients in the protoplanetary disk. With the International Ultraviolet Explorer and Hubble Space Telescope, he made the first space-based telescopic observations of comets and of water emission from asteroid Ceres.

Mike was the principal investigator for NASA’s groundbreaking Deep Impact mission. In 2005 Deep Impact performed the first-ever excavation and scattering experiment of the nucleus of comet 9P/Tempel 1; that work paved the way for future landers on cometary surfaces and comet sample-return missions. From 2006 to 2013, Mike used the repurposed Deep Impact spacecraft, termed EPOXI, to obtain some of the first space-based exoplanet light-curve and microlensing measurements and rotationally resolved full-disk, photometric observations of Earth and Mars. In 2010 EPOXI made the first in situ flyby of a hyperactive carbon dioxide sublimation-driven comet, 103P/Hartley 2. Mike was a coinvestigator of the team of astronomers that used the repurposed Stardust-NExT spacecraft to revisit the nucleus of comet 9P/Tempel 1 and identify changes in its surface as it evolved one solar orbit later. He also served on the science teams for the European Space Agency’s revolutionary Giotto and Rosetta comet flyby and rendezvous missions.

Another of Mike’s enduring legacies is the wide respect he had from and tremendous influence he had on cometary scientists around the world. In 1984 he helped establish and lead the International Halley Watch, one of the modern era’s first international worldwide observing campaigns, to follow the historic return of comet Halley in the mid 1980s, and in 1993 he formed and led a coordinated international team to study comet D/Shoemaker–Levy 9’s historic impact into Jupiter. He was the principal investigator of the NASA Planetary Data System’s Small Bodies Node, which processes and curates solar-system data sets from spacecraft and ground-based telescopes for use by future generations of astronomers.

Mike’s scholarly advice was requested by the most important US science organizations—NASA, NSF, and the National Research Council among them—yet he also made time to discuss science with young researchers he would meet at conferences. He also served his fellow astronomers with stints as chair of the University of Maryland’s department of astronomy and the American Astronomical Society’s division for planetary sciences (which awarded him the 2008 Gerard P. Kuiper Prize for lifetime scientific achievement), and as president of the solar-system division of the International Astronomical Union.

Because of his leadership, scientific drive, and generosity, the University of Maryland became a center of the cometary universe. By many counts, he trained, collaborated with, and employed more than 80% of the pre-Rosetta generation of cometary astronomers. Mike’s students remember him for encouraging them to try new projects and supporting them to actually see them through. His scientific lectures were always pan-disciplinary, well argued, and concise but also illuminating, even to experts in the field.

An avid sailor, celestial navigator, husband, and parent, Mike was well loved by his students and highly respected by the planetary-science community, who will miss his rapier wit and love of logical argument for all things cometary. But if they look up some night, they may see a piece of him in the sky: Asteroid 3192 was named A’Hearn in his honor.

More about the authors

Carey M. Lisse, John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Maryland.