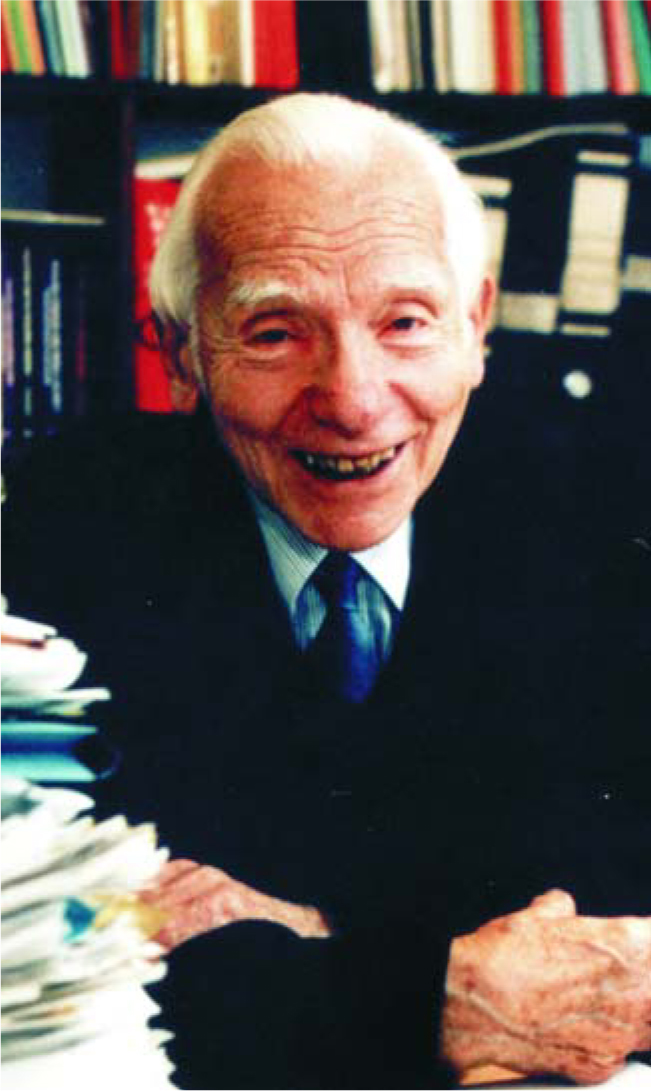

Joseph Rotblat

DOI: 10.1063/1.2207054

Joseph Rotblat

Joseph Rotblat, born in Warsaw, Poland, on 4 November 1908, died in London on 31 August 2005. Only in the last part of his life did he receive the honors due him, including knighthood and membership in the Royal Society, which came his way after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995. For most of his life, he stood in opposition to the establishment: He strongly opposed the nuclear arms race and advocated the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

Rotblat’s early years were happy and comfortable, but his family was thrown into extreme poverty when his father’s business collapsed during World War I, and he nearly starved. But thanks to his intelligence and perseverance, he obtained a scholarship to the Free University of Poland in Warsaw, and, specializing in the relatively novel field of nuclear physics, he received a doctorate in 1938 from the University of Warsaw.

As soon as the news about the possibility of uranium fission appeared, he recognized the possibility and implications of a nuclear chain reaction and measured experimentally the number of neutrons produced in the fission reaction. That work was done in Warsaw in 1938.

In 1939 he was offered a one-year fellowship to work with James Chadwick, the discoverer of the neutron, at the University of Liverpool. Rotblat moved to Liverpool alone, and later attempted to fetch his wife, Tola. But she was too ill to travel, war broke out, and she became trapped in Poland. She and many of Rotblat’s Jewish colleagues were killed by the Nazis.

The Chadwick group was particularly competent in nuclear physics, and was soon involved in classified research in England on the feasibility of building nuclear explosive devices. Eventually the entire group moved to Los Alamos and became part of the Manhattan Project. Rotblat, who had envisioned the possibility of nuclear weapons while still in Poland, took part because he perceived the need for the Allies to obtain, before Hitler’s Germany, a weapon that might determine the outcome of the war. But Rotblat also felt a strong ethical repugnance to working on the development of such a terrible instrument of indiscriminate killing. When it became clear at the end of 1944 that Nazi Germany would be defeated and no longer posed a danger of acquiring a nuclear weapon capability, Rotblat sought and obtained permission to return to Liverpool. He was perhaps the only scientist who decided on ethical grounds to abandon the Manhattan Project, a decision that identified him—although quite unjustifiably—as a potential security risk.

In Liverpool, Rotblat performed research that was instrumental in improving the photographic emulsion technique to reveal elementary particles. His work eventually allowed the group of Cecil Powell to identify the pi meson.

The news of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 was a terrible shock for Rotblat. He eventually decided to abandon nuclear physics and devote his scientific activity to the medical applications of radioactivity. He acquired British citizenship and in 1950 became a professor of medical physics at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, part of London University, where he served until his retirement in 1976. He pioneered the therapeutic uses of particle accelerators and became a world authority on the effects of nuclear radiation on humans; among many other achievements in this field, he was largely responsible for two major World Health Organization studies on the subject.

When in 1954 Bertrand Russell, worried by the development of enormous arsenals of thermonuclear weapons (H-bombs) of practically unlimited destructive power, drafted what is now called the Russell– Einstein Manifesto, he consulted Rotblat. Russell was concerned that his lack of specific competence in the physics of nuclear weapons might cause him to write something less than completely correct. Rotblat was the youngest among the scientists who signed the manifesto. In addition to Russell and Einstein, the other signatories were Max Born, Percy Bridgman, Leopold Infeld, Frédérick Joliot-Curie, Hermann Müller, Linus Pauling, Cecil Powell, and Hideki Yukawa. For many years, Rotblat was the last survivor of that eminent group.

After the manifesto was issued in July 1955 to great media attention, Rotblat endeavored to organize a meeting of scientists having different ideological and geopolitical backgrounds. Such a meeting was called for by the manifesto to lessen the danger of catastrophic use of nuclear weapons. The meeting eventually took place in July 1957 in the village of Pugwash in Nova Scotia, Canada, and constituted the beginning of the Pugwash Movement.

Rotblat dedicated the rest of his life to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs; he served as the Pugwash Secretary General for the first 14 years (1958–72), and always remained the group’s main spirit. His extraordinary commitment to nuclear disarmament and peace, his great organizational skill, and his exceptional human qualities have undoubtedly been the main engine of the successes of Pugwash. The movement’s behind-the-scenes activity is widely credited with facilitating the major arms-control achievements of the cold war era and with the improvement of international relations and the opening up of the Soviet intelligentsia that led to the cold war’s end. Indeed, in 1995 the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament decided for the first time in its history to assign the Nobel Peace Prize equally to an organization and to an individual—the Pugwash Conferences and Rotblat. Eighty-seven years old and still very active, Rotblat was serving as the president of Pugwash at the time. The short citation of the prize reads, “For their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics and, in the longer run, to eliminate such arms.”

The death of Jo (as he was called by his friends) is a terrible loss, and too little time has passed for that wound to be healed. Yet if we contemplate his long and fruitful life with all its achievements, we must not be sad. We—and we can presume to speak here in the name of so many other friends and admirers of Jo—rather recommit ourselves to work toward the two goals that he identified as the main tasks of his mature life: the first, which he liked to characterize as a short-term goal, the total prohibition and elimination of nuclear weaponry; and the second, on a longer time scale, the abolition of war as an accepted social institution for the resolution of conflicts.

PUGWASH CONFERENCES ON SCIENCE AND WORLD AFFAIRS

More about the authors

Francesco Calogero, 1 University of Rome I “La Sapienza” .

Robert Hinde, 2 St. John’s College, Cambridge, UK .