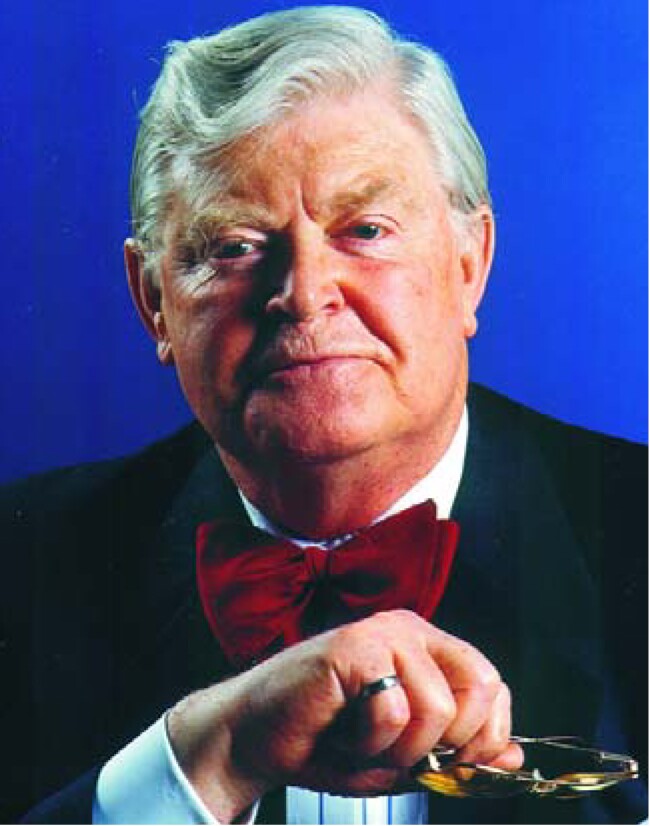

David Allan Bromley

DOI: 10.1063/1.2117834

David Allan Bromley, an exceptional scientist, educator, and respected leader in science and technology policy, died of a heart attack on 10 February 2005 after teaching a class at Yale University. His eminent scientific career molded the field of nuclear structure. He had more than 500 publications and excelled at exploiting new technologies for basic research. His highly distinguished contributions as an adviser on S&T policy to industry and government culminated in his serving as science adviser to President George H. W. Bush.

Allan was born on a farm in Westmeath, Ontario, on 4 May 1926, and attended the proverbial one-room schoolhouse. Concluding that he was destined for bigger things, he parlayed a prizewinning essay on the evils of alcohol into a scholarship and, ultimately, into a career that eventually reached the White House. He received a BS in engineering in 1948 at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and his PhD in physics at the University of Rochester in 1952, under Harry Fulbright. His thesis topic was the ground-state parities of nuclei with A = 14.

From 1955 to 1960, Allan was at Chalk River Laboratories, where an exceptional group of scientists launched a golden age of nuclear physics in Canada. Using the lab’s tandem Van de Graaff accelerator, they extended the new concept of nuclear deformation to light nuclei and discovered resonances in carbon-12 on carbon-12 scattering that, later at Yale, led to the concept of nuclear molecules. The group was so prolific that the Canadian Journal of Physics became almost required reading during that period.

Two of Allan’s signature characteristics emerged around that time: his penchant for bow ties and his appreciation of the power of technology in science. He helped pioneer the use of silicon semiconductor particle detectors and high-resolution Ge(Li) (germanium doped with lithium) gamma-ray detectors, and forever altered the trajectory of nuclear spectroscopy.

Allan went to Yale in 1960 and revolutionized nuclear physics by leapfrogging the scale of tandem energies with the MP (“Emperor”) accelerator. The accelerator was housed at Yale’s A. W. Wright Nuclear Structure Laboratory (WNSL), which he founded in 1961 and directed from 1963 until 1989. By enabling Coulomb-barrier nuclear reactions with much heavier projectiles, the accelerator opened up new research areas. In the ensuing years, Allan became the father of heavy-ion physics, a status that was later cemented with the multivolume Treatise on Heavy-Ion Science (Plenum Press), published during the mid- to late 1980s.

The lab immediately became a leading center for nuclear structure research. From 1965 to 1989, WNSL produced more PhDs in experimental nuclear physics than any other institution in the world. In the late 1960s, Allan again showed his innovative use of technology: He collaborated with former student Joel Birnbaum, then at IBM, to install one of the first online computer data-acquisition and accelerator control systems.

Allan was chair of the Yale physics department (1970–77), Henry Ford II Professor of Physics (1972–93), and Sterling Professor of the Sciences (1993 until his death). Called on to reprise his early engineering skills to restore that field at Yale to its early glory, Allan served as dean of engineering from 1994 to 2000 and was the driving force in launching the hugely successful new bioengineering and environmental engineering programs.

Allan loved teaching and he was loved by his students, to whom he was an exceptional, if demanding, mentor and supporter, available no matter how busy he was. He had an innate ability to see what physics question might be troubling a student and would say just the right words to dispel clouds of confusion.

Allan indeed had a way with words, albeit sometimes exaggerated. We re-call the “Bromley factor” of 5280 relating to Earth’s oblateness; a crisp comment to a student who wanted to take a short break for choir practice, reminding him that he had a watershed, career-altering decision to make; an insight into the nature of matter; or guidance in science policy. Another appealing trait was Allan’s intense loyalty. He became lifelong friends with several of his students, including Birnbaum and Joe Allen, who carried a 1965 publication that he coauthored with Allan on a Columbia shuttle mission.

Allan soon emerged as an influential adviser in science and government circles: He helped found the American Physical Society’s division of nuclear physics in 1966, chaired the physics survey committee of the National Academy of Sciences; (1969–73), and was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1981) and APS (1997). He was on President Ronald Reagan’s White House Science Council (1981–89) and the National Science Board (1988–89).

In 1989, President Bush appointed Allan the first assistant to the president for S&T, a cabinet-level position with direct access to the president, with whom he also had strong personal ties. Allan simultaneously served as director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (1989–93) and greatly enhanced its influence.

Allan was an especially effective adviser who advanced an ambitious agenda for S&T. He quickly learned how things got done in the White House, formed the necessary alliances, worked with the relevant federal agencies and the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology—which he cochaired from 1989 to 1993—and convinced the president to move much of that agenda into action. To coordinate agency cooperation, Allan reinvented the Federal Coordinating Council for Science, Engineering and Technology, which was key to the success of the Global Change Research Program, among other interagency programs.

Allan’s constant preaching about the links among basic research, tech-nological advancement, and economic growth led to the first national technology policy to motivate increased cooperation between governmental and private sectors. With the support of the Carnegie Foundation, Allan established the remarkably successful Carnegie (G8) Group of top government S&T policy officials who meet in off-the-record sessions to discuss S&T issues of global importance, to improve mutual understanding, and to foster tangible international cooperative activities. Allan’s effectiveness in Washington stemmed in part from his enormous scientific accomplishments and high stature in physics, but was also due to his direct and penetrating style and tenacious approach to everything he did.

Allan received numerous honors, including APS’s 2001 Nicholson Medal and, in 1988, the presidential National Medal of Science, which is administered by NSF.

Allan possessed just the right balance of intellect, strategic thinking, creativity, assertive charm, and dogged determination to accomplish so much—in his research, his scientific administrative careers, and during his time in the White House. Science and the nation are much the better for him. He is greatly missed.

© RONSHERMAN.COM

More about the authors

Richard F. Casten, 1 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, US .

Neal Lane, 2 Rice University, Houston, Texas, US .