Visionaries Gather to Honor John Wheeler

DOI: 10.1063/1.1485571

Why the quantum? How come existence? It from bit? A participatory universe? What makes meaning? Those are some of the “Really Big Questions” of John Archibald Wheeler. Both Wheeler and his RBQs were the focus of the irresistibly titled “Science & Ultimate Reality” symposium that took place from 15 to 18 March near Princeton, New Jersey.

Wheeler has had a long and remarkable career in physics teaching, research, and public service. In 1939, he and Niels Bohr provided the first theory of nuclear fission. In the 1940s, Wheeler worked on the Manhattan Project, and in the 1950s, he helped develop the hydrogen bomb. He was central to the revival of general relativity in the 1960s; in 1967 he coined the term “black hole” and eventually convinced his colleagues of the phenomenon’s reality. In 1965, he and Bryce DeWitt launched the field of quantum cosmology. The list goes on.

The symposium was the brainchild of Charles Harper, planetary scientist and executive director of the John Templeton Foundation. According to Harper, the foundation encourages and explores research in ultimate reality, whether it be in theology, philosophy, or deep issues in physics. The foundation spent about $700 000 on the symposium project, which next year will also yield a book with 30 invited chapters, most of them written by the symposium’s participants.

More than 300 individuals, most of them physicists, attended the longweekend affair. The tone was set with the first plenary talk by the University of Vienna’s Anton Zeilinger. He discussed delayed-choice experiments, first proposed by Wheeler in 1978, and their meaning for quantum reality. Lively discussions ensued, and spilled out into the hallway.

Throughout the symposium, in fact, discussions and debates were all-embracing, simultaneously brawny and nimble, and generally cordial. Speakers in the four sessions—quantum reality, theory; quantum reality, experiment; big questions in cosmology; and emergence, life, and related topics—all touched on Wheeler’s RBQs, his research, or both. At the sessions, in the halls, and at meals one heard buzz about quantum gravity, black holes, time’s arrow, a gravity-wave transducer, parallel universes, the nature of information and its role in the universe, and a host of other gripping and tantalizing subjects.

“I worried beforehand that things might go sour,” said Harper. “There could have been some spoilers or people might have gone into eye-rolling mode. But honoring Wheeler, who is both profound and gracious, really forestalled any rudeness. The real question was, Could we get around people’s initial suspicion of the foundation’s role? In the end, the outcome was better than expected.”

Adrian Melott, an astrophysicist at the University of Kansas, was initially suspicious. “While interested in the meeting topic,” he said, “I also was on the lookout for a hidden agenda, which might be evangelism rather than science. The Templeton Foundation is certainly theistic, but that in no way colored the program. I ended up thinking about things that aren’t normally part of my research, but in principle could be. It was fun and I’m glad I went.”

The future belongs to the young

“The whole thing was a little offbeat, a little unusual,” said Ken Ford, a theoretical physicist and collaborator on Wheeler’s autobiography. “For me, the real highlight was the young researchers.”

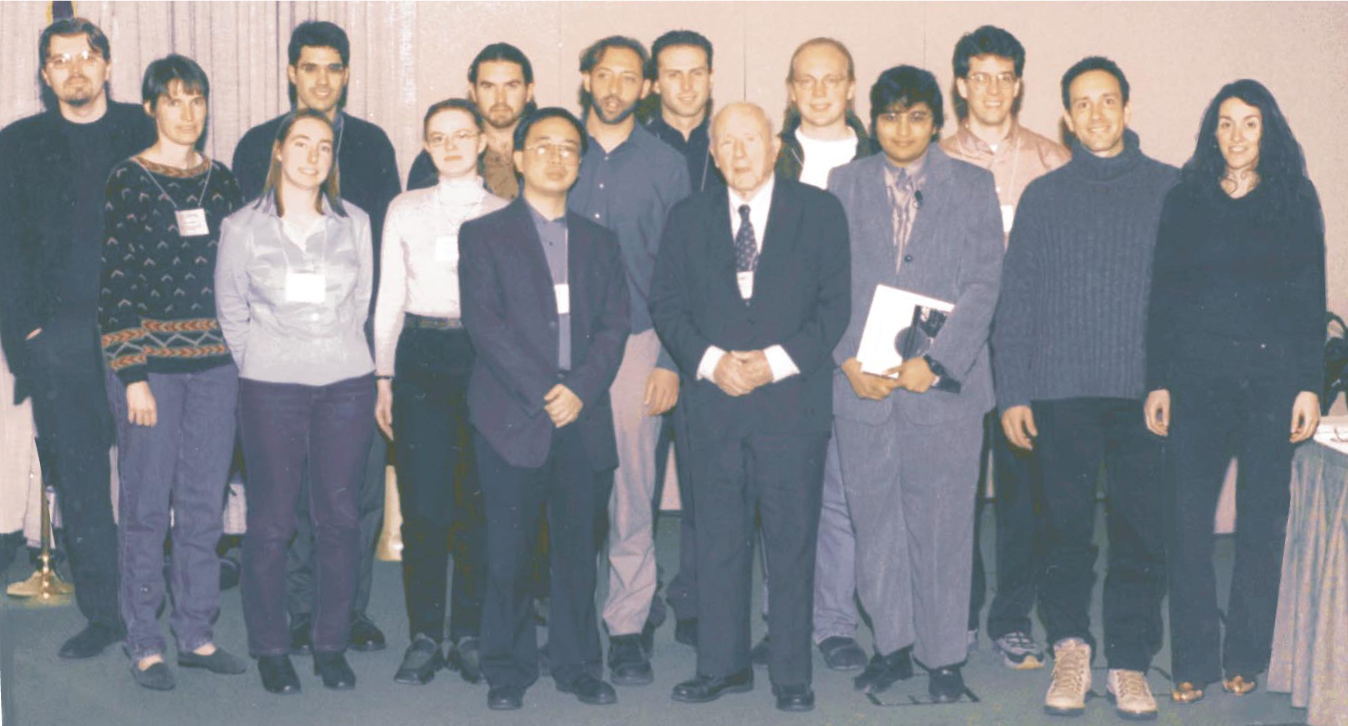

In developing the program, Harper knew he wanted scientists in their twenties involved. “In 1910, if we wanted to explore the future of physics and everyone who came was over 40, the people who mattered wouldn’t be there.” So he cooked up a Young Researchers Competition for the under-32 crowd to encourage short papers that were deep, innovative, persuasive, and relevant to Wheeler’s RBQs. Of the 64 entrants, 15 finalists were chosen (see the photo on page 28). “It was especially nice to see the gender balance and international flavor of the finalists,” said Ford. First prize was shared by Raphael Bousso and Fotini Markopoulou, who each took home $7500. Six others shared second place and received $5000 each.

The evening after the competitors’ presentations, prominent historian and religious scholar Jaroslav Pelikan of Yale University’s history department delivered the other plenary talk, entitled “The Heritage of Heraclitus: John Archibald Wheeler and the Itch to Speculate.” Like Heraclitus, Wheeler has thought deeply about war and loss. Taking the podium for a few minutes the next day, Wheeler declared that he expected the world to see a devastating war “in the next 50 years,” but was optimistic that humankind would survive and become stronger, especially when he looked at inspirational young people and deep thinkers such as those in attendance.

Wheeler added that, last year, he “had the good fortune to have a heart attack. I call it good fortune because it reminded me that time is limited. Philosophy is too important to leave to the philosophers, and I had better get busy on the most important question: How come existence?”

John Archibald Wheeler and the Young Researcher Competition finalists. From left to right: Vlatko Vedral (Imperial College, London); Mary Rowe (NIST, Boulder); Nicole Bell (NASA/Fermilab); André Stefanov (University of Geneva); Olga Khovanskaya (Moscow State University); Jeremy O’Brien (University of Queensland); Jianwei Pan (University of Vienna); Jonathan Oppenheim (The Hebrew University, Jerusalem); Michael Murphy (University of New South Wales); Wheeler; Mark Topinka (Stanford University); Anita Goel (Harvard University); Steven Gubser (Princeton University); Raphael Bousso (University of California, Santa Barbara); and Fotini Markopoulou (University of Waterloo, Canada). Not shown is Jiangping Hu (Stanford). This is a digital composite of two photos.