US mulls the next steps in human spaceflight

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1287

The landing of the space shuttle Atlantis in July brought an abrupt, if temporary, end to the nearly 50-year era of US human spaceflight. As NASA endeavors to restore US-made spacecraft to orbit, it faces the prospect of cutbacks in funding to accommodate budget cuts required to raise the debt ceiling.

Congress last year rejected President Obama’s plan to put off the development of deep-space exploration vehicles and ordered NASA to have a rocket and a crew vehicle capable of interplanetary travel available by 2016. In signing that legislation, the president backed a human spaceflight program that looks very similar to that of his predecessor in office: a private-sector-led effort to develop cargo and crew vehicles for traveling to the International Space Station (ISS) and a separate NASA program to produce a spacecraft and rockets for flying to the Moon, asteroids, and even Mars. Despite Obama’s having signed the bill, Republicans are increasingly accusing the White House of dragging its feet on long-duration flight capabilities.

NASA has been funding a number of US companies since 2007 to design, develop, and build spacecraft. Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) and Orbital Sciences Corp are scheduled to begin delivering cargo to the ISS next year aboard vehicles they have been developing with a total of about $500 million in funding from NASA. The two companies also have signed commercial resupply contracts committing SpaceX to 12 cargo delivery missions and Orbital to 8 missions through 2016. SpaceX’s final demonstration flight of its Dragon cargo vehicle and Falcon 9 rocket combination is scheduled for 30 November. Assuming the success of that dry run, which is to include docking with the ISS, the company will deliver its first payload in February. Orbital is running a few months behind SpaceX. The first test flight of its Cygnus cargo vehicle and launcher combination will occur in February, and cargo delivery will begin in the second quarter of 2012.

The now total dependence of the US on Russia’s Soyuz rockets for human access to the ISS was brought home in dramatic fashion on 24 August, when a Soyuz rocket carrying an unpiloted cargo vehicle destined for the ISS was destroyed several minutes after launch. “We believe the Soyuz crew capsule would have performed an abort and a ballistic entry if this same failure occurred on a Soyuz booster during a crew flight,” administrator Charles Bolden told NASA employees on 2 September. Laurie Leshin, NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration systems, says the Soyuz vehicle and its launcher “have been historically extremely reliable.” But the Russians won’t launch another Soyuz booster until their investigation is complete and the rocket is revalidated, a process that will include at least one unmanned flight, Bolden said. A prolonged hiatus could necessitate the evacuation of the ISS later this year.

Leshin says Atlantis “really stocked the shelves with supplies” on its last mission, and the ISS now has sufficient stores to last through next spring. By then the European Space Agency’s automated transfer vehicle is due to dock. And the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s HTV2 transfer vehicle completed its first delivery of cargo to the ISS early this year.

Retro designs, novel contracts

Through NASA’s commercial program to develop ISS crew transports, four contractors were awarded a total of $270 million in April to mature their spacecraft designs. They are expected to receive another round of funding from the agency next year. Bolden said readying a human-qualified transport will take three to five years. Three of the designs are Apollo-like capsules, except for the number of seats—seven, compared to Apollo’s three.

SpaceX, headed by PayPal co-founder Elon Musk, is adapting its Dragon–Falcon combination; Blue Origin, a venture being financed by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, would use a capsule and launcher that can return softly to Earth in an upright position, cushioned by thrusters.

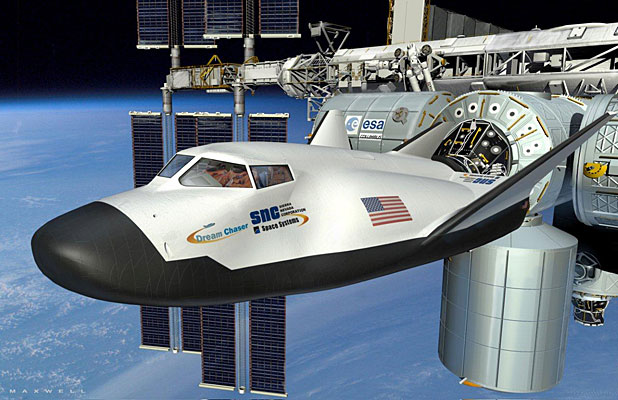

Sierra Nevada Corp is the sole NASA commercial contractor working on a winged crew vehicle. Its Dream Chaser would be built for runway landings. Boeing is working on a capsule design it calls CTS-100. Boeing and SpaceX have chosen the Apollo-era splashdown method for bringing ISS crew members back to Earth.

Blue Origin had performed two successful “short hop” tests. But on 2 September, Bezos reported a major setback: A rocket had veered off course after launching from the company’s west Texas launch site and was automatically destroyed. “Not the outcome any of us wanted,” Bezos wrote, “but we’re signed up for this to be hard.” He added that Blue Origin is already working on a new launch vehicle.

Sierra Nevada, Boeing, and Blue Origin all propose to launch their vehicles atop Atlas V rockets, which are manufactured by United Space Alliance, a Lockheed Martin–Boeing joint venture. Apart from the Soyuz, no currently available rocket is approved by NASA for human flight.

With its commercial ISS contractors, NASA has used an authority that is unique among federal agencies. Known as Space Act agreements, the contracts are exempt from standard federal acquisition regulations. Former NASA administrator Michael Griffin, who has made no secret of his opposition to Obama’s human exploration policy, frets about the lack of government oversight and accountability provisions in the Space Act contracts. “I’ll offer you a prediction,” says Griffin. “Sometime in the next four or five years, a company which took a bunch of money from the government up front will fail to deliver on what they said. Or there will be an accident, or there will be a financial impropriety.” Lawmakers, he continues, will then ask, “Where was NASA’s supervision?” NASA officials will cite the 2010 authorization act in replying, “you told us not to.” Also worrisome, Griffin argues, is the lack of a backstop if none of the commercial developers are able to build human-qualified vehicles. In that case NASA will have no alternative other than continuing to pay for seats on Soyuz.

Leshin says the commercial crew program is still “in its infancy,” and she acknowledges that continued reliance on Soyuz is “obviously not our first choice. We’d rather have American-supplied commercial seats available.” Bolden estimated that a qualified human transport system for the ISS will be available in three to five years.

But longtime space-policy observer John Logsdon of the George Washington University isn’t worried about the success of the human transport program. “To think that none of the four companies can build a spacecraft equivalent to what we did 40 years ago seems implausible,” he says.

Bolden seems comfortable with the commercial ISS supply program. “There’s nothing different except the procurement mechanism that we are using,” he told a National Academies roundtable on 25 August. The prime contractor mechanism that NASA used for spaceflight programs, including the space shuttle and Apollo, is too expensive, he maintains. The new approach provides “focused insight/oversight, specifying to industry—where appropriate—what we need, instead of how to build it,” he told the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology in July testimony. Still, Bolden admitted the agency continues “wrestling with how we do development” with the ISS contracts, which are fixed price. ”The risk is that if something goes wrong, how do we get it fixed?” For cargo, at least, the approach appears to be succeeding so far. “The fact is we are months away from having an American capability to take cargo to the ISS,” Bolden said.

Missed deadlines, new goals

Long-duration human travel to destinations beyond low-Earth orbit awaits development of a more advanced spacecraft—a capability that Congress is prodding NASA to provide as quickly as possible. The agency announced last year that it will continue development of the Orion crew vehicle that had been part of President George W. Bush’s Constellation program. Lockheed, which had been the prime contractor on the Orion program, will continue to manage what NASA now calls the multipurpose crew vehicle. Some $9 billion has already been spent on the Orion.

Although Congress set a deadline of January 2011 for a decision on an architecture and plan for building the heavy-lift booster, or Space Launch System (SLS), NASA didn’t announce its choice until 14 September. Both stages of the rocket will be liquid fueled. The first-stage rocket engines are the same design used for the space shuttle’s main engines. The second-stage engine will be the same engine that was going to be used in the Constellation launcher. Both will be openly competed.

The White House Office of Management and Budget had ordered multiple reviews of the plan submitted by NASA months ago. One review, an independent cost estimate by consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, offered a qualified endorsement of NASA’s figure, saying the agency had made highly optimistic assumptions about its ability to improve the efficiency of the development program. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas, the ranking Republican member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, charged that the holdup has resulted in the layoff of thousands of Constellation and shuttle program workers who could have been kept to work on the SLS.

Logsdon, though, says the administration’s caution shouldn’t come as a surprise, given news reports that the rocket will cost $38 billion over 10 years. Griffin claims that the SLS should cost nothing close to that; the administration’s goal, he contends, is to ensure that the heavy-lift launch vehicle that Congress demanded in 2010 is never completed. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy declined repeated requests for comment.

The Obama administration has set a goal of landing humans on an asteroid in 2025, followed by a trip to Mars in the mid 2030s. The Moon, which Bush had proposed as the destination in 2020, isn’t on the Obama administration’s itinerary. Bolden told the House Science committee that he doesn’t rule out a return to the Moon, or visits to Earth–Moon Lagrange points.

An artist’s conception of the Dream Chaser proposed by Sierra Nevada Corp, one of four commercial designs that NASA has been funding as vehicles that would transport crew to and from the International Space Station

SIERRA NEVADA CORP

Cygnus, Orbital Sciences Corp’s unmanned cargo vehicle, is shown in this artist’s rendering as it approaches the International Space Station.

ORBITAL SCIENCES CORP

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org