Undergraduate physics programs at HBCUs: Can we stop the losses?

DOI: 10.1063/1.3455321

Physics-degree-granting programs at historically black colleges and universities are in serious jeopardy. With each passing year, HBCUs are giving out fewer and fewer physical science degrees, and several physics programs are at risk of closing their doors. According to data published by NSF, the percentage of bachelor’s degrees in the physical sciences awarded to African Americans by HBCUs fell from 43.7% in 1998 to 37.4% in 2007.

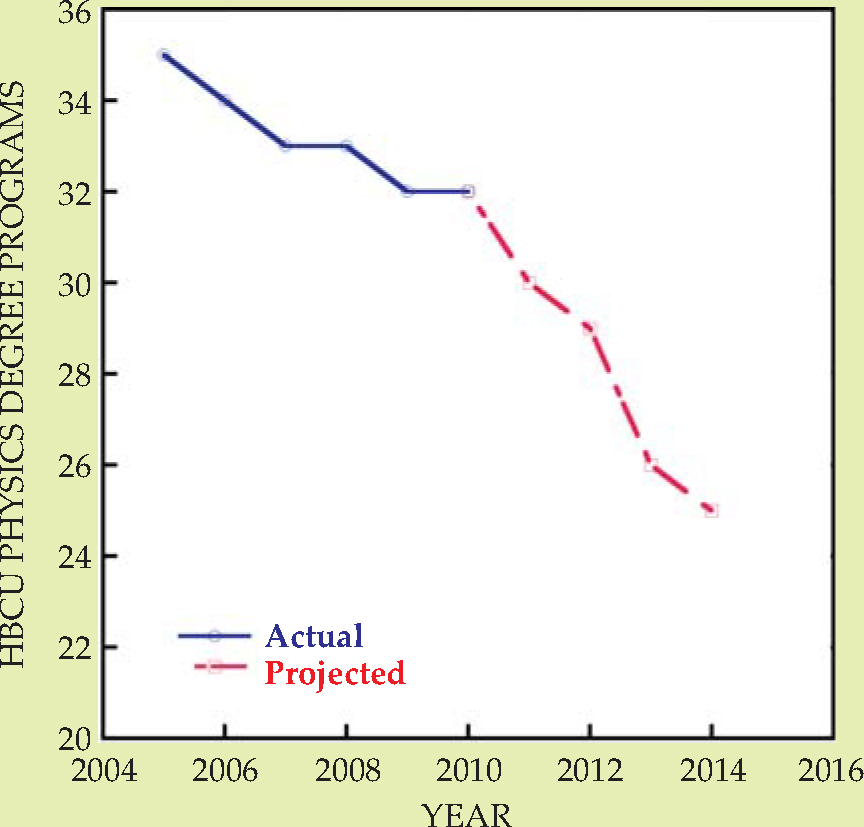

Historically, more than half of all African Americans who have earned physics bachelor’s degrees have done so at one of 35 HBCUs. Over the past five years, three HBCU physics programs—nearly 10% of the total number of programs—lost their degree-granting status, while only one new program was added. There are now 32 undergraduate physics degree programs at HBCUs. The total number of physics bachelor’s degrees awarded in the US in 2007 was 5755. Although that number represents the highest production level in nearly 40 years, the number of physics bachelor’s degrees earned by African Americans has declined, as has the percentage of all physics bachelors who are African American. If HBCU physics programs fold, then the likelihood of African Americans earning degrees in physics will drop significantly. The downward trend in the statistical data, as seen in figure 1, is evidence that the problem is dire. As a senior, active member of the HBCU physics community, I speak from direct experience.

Figure 1. Physics-degree-granting programs at historically black colleges and universities. The number has declined dramatically since 2005, and the decline is projected to continue.

(Source: Data for 2005–10 are from the American Institute of Physics Statistical Research Center, College Park, Maryland.)

African Americans have greatly contributed to all aspects of society. A few examples include Charles Drew, in medicine, who pioneered blood transfusions and blood storage techniques that led the way to large-scale blood banks; Thurgood Marshall, in law, who successfully argued the landmark desegregation case of Brown v. Board of Education and who later became a justice of the US Supreme Court; Garrett Morgan, in engineering, who invented the gas mask and the traffic light; and Matthew Henson, in exploration, who was part of the first expedition to reach the North Pole.

The first research published in a scientific journal by an African American physicist was in 1919, when Elmer Imes published his work on near-IR absorption measurements of diatomic gases in Astrophysical Journal. Imes subsequently founded a physics program at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, to educate other African Americans. Physics programs were eventually established at other HBCUs, and they have produced astronauts, internationally recognized scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs, university presidents, and a former NSF director. African American physicists, in fact, have contributed significantly to Nobel Prize–winning research; unfortunately, their key contributions were not duly recognized. Indeed, Herman Branson reportedly co-invented the alpha helix structure in protein while working under Linus Pauling at Caltech.

African Americans have extended the boundaries of performance in music, athletics, and fine arts, and the same could happen in physics. Physics programs at HBCUs attract and cultivate intellectual talent that might otherwise be overlooked. In addition to preparing highly qualified students for advanced studies, HBCUs have also specialized in bolstering the academic fundamentals for less well-prepared students to better equip them for graduate work.

A good and right thing

The value of diversity in the workplace is well known and cannot be overstated. Culturally diverse teams have been shown to produce ideas that are higher quality, more creative, and more feasible than those produced by more homogeneous groups. In addition to having a financially rewarding career, a physicist can have a broader impact simply as part of an educated citizenry. Diversity in physics is good for science and for the African American community, and it is also the right thing to do. Statistical reports by the American Institute of Physics (AIP) and NSF on minority degree production indicate that HBCU physics programs are still very much needed.

Presently, some seven HBCU physics programs are seriously at risk of being shuttered within the next few years. An at-risk program has fewer than four faculty members or has produced only one graduate in the past three years. Additionally, in private conversations with colleagues at other HBCU programs—ones that are not technically at risk—I hear much anxiety expressed about the viability of their degree programs. Although the concerns might appear to be local, they present a clear national challenge for federal funding agencies to recognize and respond with fiscal actions to stop the downward trend. To weather the storm, direct investments in physics faculty, infrastructure, and student support should be made to preserve these national treasures of intellectual capital.

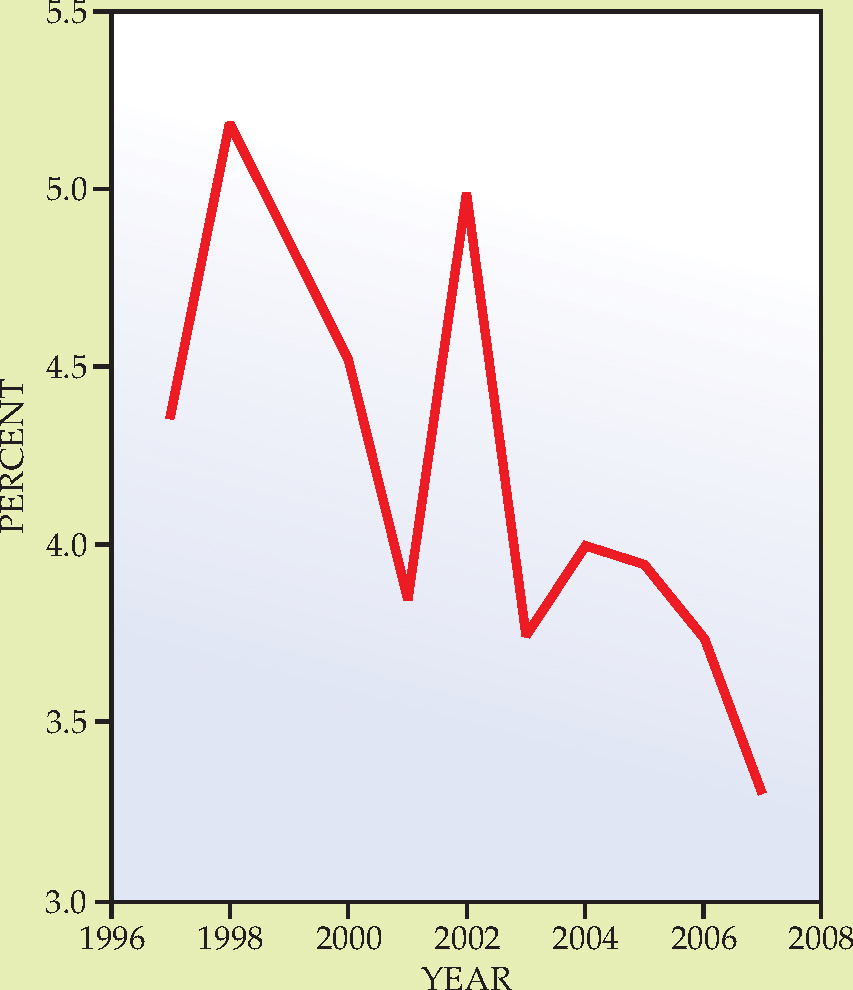

A few federally funded programs, such as NSF’s HBCU Undergraduate Program and NASA’s Minority University Research and Education Program, are in place to increase underrepresented minority participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). However, the fact that only 3.7% of bachelor’s degrees in physics are held by African Americans clearly shows that current programs are not working well for physics (see, for example, figure 2). Federal funding agencies need to develop a new approach to increasing diversity in physics. With federal agencies awarding millions of dollars annually in the name of increasing diversity in STEM, it would be a travesty for HBCU physics programs to be allowed to continue their decline with no focused national program to reverse the trend.

Figure 2. Percent of physics bachelor’s degrees earned by African Americans.

(Source: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, http://www.nces.ed.gov/IPEDS.)

According to data from NSF and AIP, African Americans earned 182 bachelor’s degrees in physics in 2002; that number had fallen to 144 by 2007. As a whole, non-HBCU institutions are still not graduating African Americans in physics in significant quantities. On the other hand, those institutions have been successful in improving their minority degree production levels in various fields of engineering. I submit that it can be done in physics as well. What are engineering departments doing right that physics departments could emulate? In the near term, the reality that accompanies the correlation of the number of HBCU physics programs with the number of African American physicists must be recognized. African American physicists will become increasingly rare if federal funding agencies choose not to take deliberate action to preserve HBCU physics programs.

Many factors are leading to the loss of HBCU physics programs. They include too few undergraduate scholarships, low visibility of career opportunities, a lack of instructional and research infrastructure, and very little executive-level administrative support. But the common denominator is money.

Dollars and sense

The shortage of HBCU physics programs is an ongoing problem that is now being made critical by the overall US financial picture. Most historically black educational institutions do not have the cushion (for example, large endowments) to weather economic storms.

As serious challenges to the economy continue, state higher-education budgets are being slashed. Less available funding impacts university administrators, who respond by looking for programs to eliminate in order to balance budgets. Unfortunately, at small and often underfunded HBCUs, physics programs are viewed as nonessential because of their relatively small numbers of majors and graduates. With little support, they become weakened and more vulnerable for program reductions. Administratively, it is easier to justify eliminating an academic program with 3 to 4 faculty members than one with, say, 10 to 12 faculty members. The unintended consequence of those seemingly small local actions is a large-scale, deleterious, cumulative effect across the physics community.

People tend to lump all minorities together when dealing with diversity issues. Sometimes that is appropriate; however, this is not one of those times, and the data must be disaggregated. Statistically, Hispanics and women are gaining ground in physics much faster than African Americans. According to NSF statistics, during the period 1997-2006, the number of physics bachelor’s degrees among Hispanics increased 73.1%, from 119 to 206; among women the increase was 45.1%, from 652 to 946; and for African Americans the increase was only 15.5%, from 148 to 171.

In 2007 the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities issued a report showing that HBCUs consistently receive 3% of the total federal funds awarded to all institutions of higher education, despite the President’s Board of Advisors setting a goal of 10%. In fiscal year 2005, 32 federal agencies awarded almost $105.5 billion to institutions of higher education, with HBCUs receiving $3.5 billion. There appears to be a limiting factor on the level of annual award percentages to HBCUs despite the overall dollar increases in federal department and agency awards. According to the report, the board believes that special attention by the president, the secretary of education, and the heads of federal education-funding agencies should be given to increasing the number of agencies that establish and administer dedicated HBCU programs. The return on investment would be beneficial to all stakeholders and the nation as a whole.

Physics and the geosciences lag behind the other STEM areas in diversity. The alarm has been sounded with this wake-up call, and I urge federal funding agencies—and the entire physics community—to partner with HBCU physics departments and the National Society of Black Physicists to avoid this pending national tragedy. A turnaround can begin with a meeting between HBCU physics chairs and federal agency program heads in which all parties provide direct input on what will actually work on the ground at those institutions. Responses should be gathered and the feedback consolidated into a nationally coordinated, pragmatic plan.

More about the authors

Quinton Williams (quinton.l.williams@jsums.edu

Quinton L. Williams, Jackson State University, Jackson, Mississippi, US .