Spin excitations in a cavity hop coherently over long distances

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4158

Quantum mechanics is as counterintuitive as it is in large part because of its nonlocality. Particles can be entangled with other particles, no matter how far away (see Physics Today, August 2017, page 14

Stanford University’s Monika Schleier-Smith (shown in her lab in figure

Figure 1.

Monika Schleier-Smith (left) observes with an IR viewer as her student Emily Davis adjusts a pair of mirror mounts. In the background is a second table where the researchers cool and trap a cloud of rubidium atoms. Optical fibers carry light between the two parts of the experimental setup.

DAWN HARMER

Driving a spin exchange

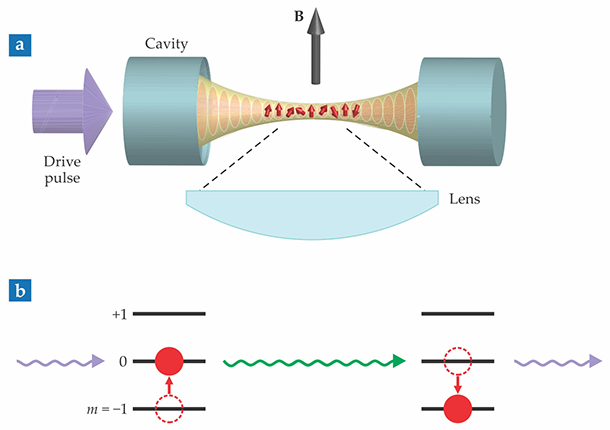

The experimental setup is shown schematically in figure

Figure 2.

Spin-exchange interactions among atoms in an optical cavity. (a) A cloud of atoms (red) is held in a one-dimensional array of optical traps (orange). A magnetic field B induces Zeeman splitting, and the lens enables imaging of the cloud from the side. (b) When a photon (purple) from a drive pulse scatters inelastically off an atom, it changes the atom’s spin state and creates a virtual photon (green) of a different energy. The virtual photon then induces a spin change of equal and opposite energy elsewhere in the cloud. (Adapted from ref.

By driving the cavity with a laser pulse of a suitably chosen wavelength, the researchers set off a flip-flop process like the one shown in figure

The drive-pulse wavelength is chosen so that the virtual photons are almost, but not quite, resonant with a cavity mode. If they were exactly on resonance, they would be able to exit the cavity without ever completing the spin flip-flop. The slight detuning ensures that the virtual photons have nowhere to go but to scatter off another atom.

Several recent experiments have used similar setups to produce collective spin interactions among atoms in cavities. 2 But until now they’ve focused on controlling and probing the atoms through global degrees of freedom, such as the total magnetization or the intensity of the light exiting the cavity. Schleier-Smith and colleagues introduced the new capability to manipulate and measure the spin states locally so they can directly see where in the cloud the spin excitations are located.

State-sensitive imaging is a standard technique in cold-atom physics: The spin states are mapped by driving them, one at a time, through a closed-cycle excitation loop that produces detectable fluorescence. But it’s challenging to implement in the context of an optical cavity. Traditionally, when researchers use an optical resonator to concentrate light in a small space, they make the whole resonator small. Schleier-Smith and colleagues used a different setup, a so-called concentric configuration, with curved mirrors separated by nearly twice their radius of curvature, a distance of several centimeters. A concentric cavity is extremely sensitive to misalignment of its mirrors. But it concentrates light tightly at its center while leaving plenty of room to introduce imaging laser beams from the side.

Toward spatial control

Figure

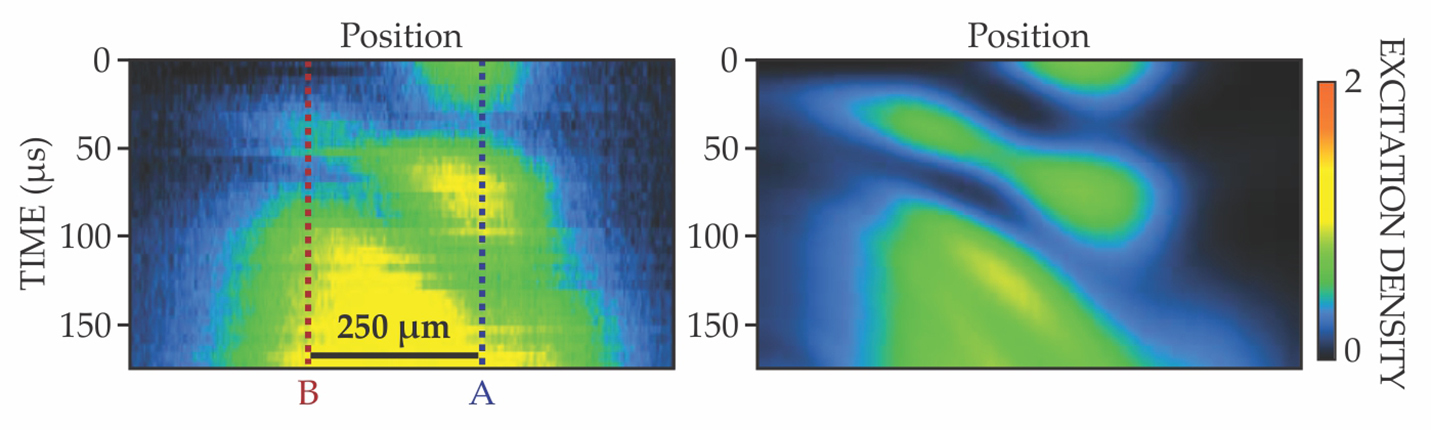

Figure 3.

Nonlocal hopping of a spin excitation as captured by experimental data (left) and a theoretical model (right). The excitation was prepared at position A at time 0. Turning on the drive pulse causes the excitation to quickly hop to position B, closer to the cavity’s center. It then slides back to A, and at time 100 µs hops again. (Adapted from ref.

The hop destination is always position B because that’s the part of the cloud nearest the cavity center, where the light intensity and thus the light–atom coupling is strongest. The subsequent sliding is a more complicated effect, but it too is explained by the inhomogeneity of cavity light. Over the course of the experiment, the overall excitation density goes up; that’s because the experimental conditions aren’t quite perfect for ensuring that the flip-flops are complete. The virtual photons are close enough to resonant that some of them do leak out of the cavity, so some spin excitations are not matched with de-excitations elsewhere.

Despite those complications, the results are reproducible. The data in figure

The researchers are working on ways to control where the hopping spin excitations end up. For example, by making the applied magnetic field (and thus the Zeeman splitting) spatially inhomogeneous, they could restrict which pairs of atoms can mutually interact to participate in a flip-flop. Another possibility is to replace the end-on drive pulse with drive lasers incident from the side of the cavity to target specific regions of the atom cloud. Between those two approaches, it should eventually be possible to engineer any desired pattern of interactions between pairs of atoms.

Excitation hopping is at its heart a classical phenomenon: Although the atoms interact nonlocally, no nonlocal correlations are involved. But the same physics of the spin flip-flop can also be used to generate and manipulate entangled states. For example, when the cloud is initialized in the m = 0 state, the drive pulse creates correlated pairs of +1 and −1 spins: The number of atoms in both states must be the same, but it’s not known which atom is in which state. The long-term goal is to combine pair creation, spin exchange, and spatial control to engineer arbitrarily complicated quantum states in large numbers of atoms.

Black hole connections

Schleier-Smith’s inspiration for her experiment came from her background in quantum control: creating entangled states for specific practical purposes.

3

For example, squeezed states, in which quantum fluctuations in one variable are reduced at the expense of increasing them in another variable, have applications in metrology. (See the Quick Study by Sheila Dwyer, Physics Today, November 2014, page 72

What happens to quantum information when it falls into a black hole? It can’t just disappear without violating the unitarity of time evolution, a fundamental property of quantum mechanics: Any quantum state can be uniquely propagated forward or backward in time. In the absence of a wavefunction collapse associated with an observation, information can’t be created or destroyed.

Nor can the information stay inside the black hole’s event horizon forever—at least, not necessarily. If a black hole doesn’t take in enough new mass to balance out the energy it loses to Hawking radiation, it will eventually evaporate away to nothingness. Where will the information go?

Some mechanism must seemingly exist to allow information to leak out past the event horizon. Figuring out how that mechanism works is a daunting theoretical challenge. But experiments may be able to help, thanks to the duality, or mathematical correspondence, between gravitational systems and quantum many-body systems. (See the article by Igor Klebanov and Juan Maldacena, Physics Today, January 2009, page 28

Which physically realizable quantum systems are the duals of black holes is itself an open theoretical question. But Schleier-Smith is hopeful that her cold-atom spin-exchange experiment could provide the answer. 4 Theoretical models that attempt to solve the black hole information problem often do so by bending the familiar rules of physical locality. “They can look very strange,” she says, “because they include all these nonlocal hopping effects,” reminiscent of the hopping of spin excitations induced by nonlocal atomic interactions. “In the future, maybe we can build something in the lab that processes information like a black hole.”

References

1. E. J. Davis et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 010405 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.010405

2. M. Landini et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 223602 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.223602

M. A. Norcia et al., Science 361, 259 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3102

R. M. Kroeze et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 163601 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.1636013. I. D. Leroux, M. H. Schleier-Smith, V. Vuletić, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 073602 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.073602

4. B. Swingle et al., Phys. Rev. A 94, 040302 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.94.040302

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org