Graduate assistantship pay often falls short of a living wage

DOI: 10.1063/pt.zprc.ngji

The graduate student stipends offered by many US physics departments are insufficient to live on, even for students who split housing costs. That’s according to Physics Graduate Student Compensation: Academic Year 2023–24, a recent report by the statistical research team of the American Institute of Physics (publisher of Physics Today). The report includes the analysis of compensation data collected from more than 100 public and private PhD-granting physics departments.

For first-year teaching assistants, stipends ranged from about $18 000 to $47 000; the average was $30 000. For fifth-year research assistants, stipends were from around $20 000 to nearly $50 000; the average was $32 700. In addition to a stipend, students often receive benefits such as health insurance and free tuition.

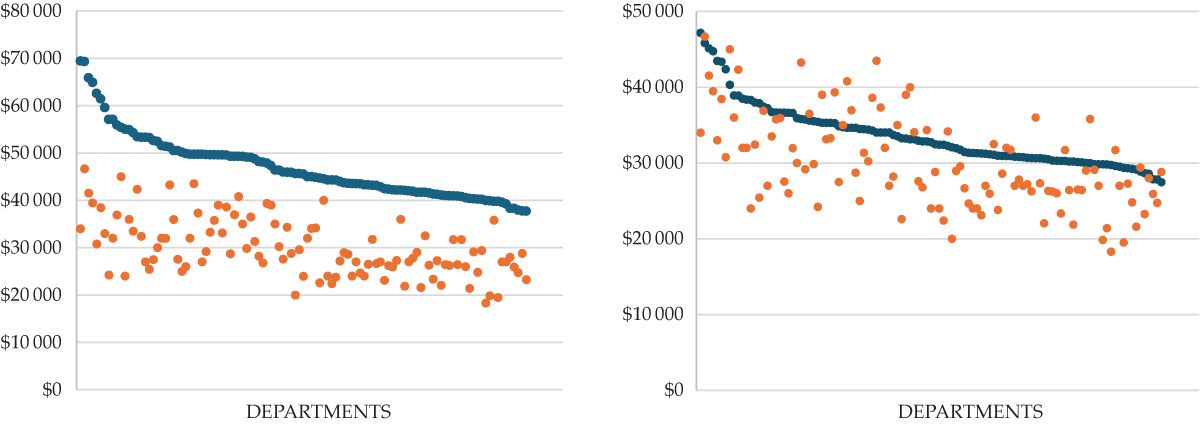

Teaching assistant stipends for first-year physics graduate students (orange dots) fall below the living wage (blue dots) for living alone in a studio apartment in cities across the US (left). Those stipends, which range from around $18 000 to $47 000, go further for students who share a two-bedroom apartment (right) but, in most cases, still fall short of a living wage. (Figure adapted from P. Mulvey, Physics Graduate Student Compensation: Academic Year 2023–24, AIP Research, 2025.)

In the 2020–21 academic year, a teaching assistantship was the main source of financial support for 56% of first-year physics PhD students. In the same period, 60% of fifth-year students were employed as research assistants, which served as their primary source of income. Service hours varied, but most departments required student assistants to work roughly 20 hours a week, according to the report. Private schools typically paid more than public ones, and schools with larger graduate programs tended to pay more than those with smaller programs.

Do teaching and research assistantships provide a livable wage? The researchers tackle that question with a calculator developed at MIT. The calculator accounts for such factors as the prices of rent, food, transportation, and other basic needs for a given location. For someone living alone in Boston or New York City, for example, the living wage is around $69 000—well above the stipend amount a physics student would receive from an assistantship. For those who live in a shared apartment, around $46 000 would do. For comparison, in St Louis, Missouri, or Toledo, Ohio, the living wage would be about $39 000 for someone living alone and $29 000 for someone sharing an apartment.

The accompanying figures plot the living wage in blue, from high to low, for a student living alone (left) or splitting costs with a roommate (right) in the locations of the institutions. The typical first-year teaching assistant stipend offered by each institution is plotted in orange. All the schools’ stipends shown in the left graph and three-quarters of the schools’ stipends shown in the right graph fall below the blue line.

For more information on compensation for physics graduate student assistantships, see https://ww2.aip.org/statistics/physics-graduate-student-compensation-academic-year-2023-24

This article was originally published online on 16 April 2025.

More about the authors

Tonya Gary, tgary@aip.org