Fluid dynamics explains ancient organism behavior

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3786

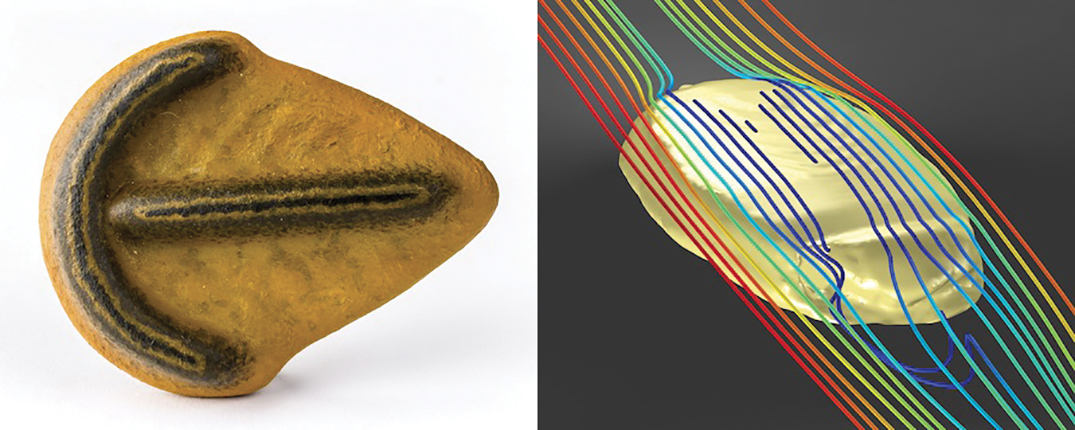

Fossil evidence tells only part of the story of an ancient organism. Take the roughly 550-million-year-old genus Parvancorina, a small, shield-shaped marine creature that doesn’t resemble any modern animal (the left image is a reconstruction). Limited to fossil analysis, paleontologists have wondered whether the organism had the ability to move through the water. Now, after a simulation in which Parvancorina were exposed to currents through computational fluid dynamics (CFD), scientists are fairly certain that it did. The CFD technique is enabling researchers to better understand how Parvancorina and other ancient creatures moved and fed.

MATTEO DE STEFANO/MUSE/CC BY-SA 3.0

At a 23 October session of the Geological Society of America’s 129th annual meeting, Oxford University paleobiologist Imran Rahman presented his work on three-dimensional digital models of Parvancorina. He developed the models based on fossils and then calculated how seawater would flow around the model organisms. Rahman found that turbulent currents flowing over the animal swept water toward specific areas of its body and that flow patterns differed depending on how the animal was oriented in the current. In the right image, the red lines represent where water flows fastest; the flow is slowest down the middle, near where the mouth (front right of the invertebrate) is located. The results suggest that not only was Parvancorina mobile, but it didn’t just tumble helplessly along—it could adjust its orientation to maximize access to nutrients.

Rahman also used CFD to explain how 510-million-year-old primitive relatives of starfish and sea urchins ate. He found that flowing water could never reach the mouthlike groove of the flat-bodied Protocinctus mansillaensis without help. Rahman concluded that the animal likely filtered water by pushing it through gill-like organs. The simulations reveal that fatter species related to Protocinctus experienced the best flow to their mouths, which suggests that body shape was a trade-off between feeding advantages and stability in the current.

The importance of the CFD work goes beyond better understanding two ancient species. Based on Rahman’s Parvancorina investigations, it’s possible that other pre-Cambrian appendage-less organisms could have been mobile. And biologists can now study Protocinctus as a step in the evolution of active feeding. Rahman encourages paleontologists to apply CFD to other puzzles in fossil taxonomy, such as the evolution of swimming and flying.