Breaking from tradition, some scientists self-publish

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2175

Earlier this year, University of Michigan condensed-matter physicist Leonard Sander sent out a mass email promoting his new textbook. “I published this book using [the online self-publishing platform] CreateSpace (a subsidiary of Amazon),” he wrote. “One reason for this choice is the out-of-control inflation of textbook prices. The downside of this publishing method is that the marketing offered by a publishing house is not available, hence this email.”

Sander’s choice is not common. The self-publishing route is more typically taken by aspiring novelists looking for a breakthrough or by amateur scientists peddling rejected theories. But for every Fifty Shades of Grey—the bestselling, originally self-published romance novel—there are thousands more self-published books that barely make a dime. And for every professional scientist who experiments with self-publishing, there are several more pseudoscientists who are publishing for validation.

Although most scientists with established or budding reputations continue to opt for traditional publishing, a few are giving self-publishing a shot. For Sander, the ability to manage the overhead costs and make his book more affordable for students was reason enough. At $42, the list price for Equilibrium Statistical Physics with Computer Simulations in Python is about half what he estimates a traditional publisher would have charged.

The self-publishing industry claims other benefits. For example, says Amazon.com

$1 per error

Despite having a poor, lingering reputation as a modern form of the vanity press, self-published books sell. “Over a third of the top 100 best sellers on Kindle [Amazon’s ebook platform] in September were [self-published] titles,” says Turner. (None of the best sellers were serious books on science.) And from 2006 to 2011, the period when a number of online self-publishing platforms launched, the annual production of self-published titles tripled, according to a 2011 report from Bowker, the official US agency that grants ISBNs.

Depending on the platform, authors pay little or nothing and do the entire layout, editing, and marketing, or they hire freelancers to do that work for them. Even when submitting to traditional publishers, “you write the book, you typeset it, you make the figures, and you send them the PDF,” says physicist Mark Newman, Sander’s colleague at the University of Michigan, who self-published his own 2012 textbook, Computational Physics after traditionally publishing his previous seven books. “[They mainly] copyedit it and handle the sales and marketing.”

But what traditional publishers also offer is “the gatekeeping—useful, independent feedback,” says Simon Capelin, editorial director for physical sciences at Cambridge University Press, which published Sander’s previous textbook. “The production of the book is the cheap and easy part.” For prepublishing feedback, both Sander and Newman sent their manuscripts to colleagues; Sander also offered the students taking his statistical physics course a dollar for each misprint they found. Both professors say their self-publishing was “an experiment”; Newman says that his book has been adopted by several physics departments, so “I feel like [the experiment] has been a reasonable success.”

Textbook prices have skyrocketed in the freshman physics category, because they demand a lot of marketing and because the used-books industry has undercut profits from their sales, says Capelin. Cambridge University Press does not compete in that category, he adds, but publishers that do, like Cengage Learning, have explicitly stated that their long-term business strategy is to transition from print to digital educational and research materials. “When Amazon first started up, I couldn’t imagine that they would have essentially replaced traditional bookstores,” says Capelin. “I don’t know that [online self-publishing] will have a similar impact on academic publishing, but I may be proved wrong.”

Blazing a trail?

Capelin says he encourages authors of some rejected manuscripts to try self-publishing, which transfers the publishing risks and the marketing costs to the author and offers feedback in the form of sales. That’s what theoretical physicist Teman Cooke did after being turned down by Cengage. His book, The First Semester Physics Survival Guide: A Lifeline for the Reluctant Physics Student, details a pedagogical approach he says he developed in seven years of teaching introductory physics courses at Georgia Perimeter College in Atlanta. Cooke says he used $6000 that he raised on the crowdfunding site Kickstarter.com

While in South Africa for the 2011 International Conference on Women in Physics, graduate students Emma Ideal and Rhiannon Meharchand learned about a book of essays by prominent women scientists in India and were inspired to produce a similar book featuring women scientists in the US. When they approached Yale University Press, however, the publisher didn’t warm to the idea, says Ideal, a student at the university.

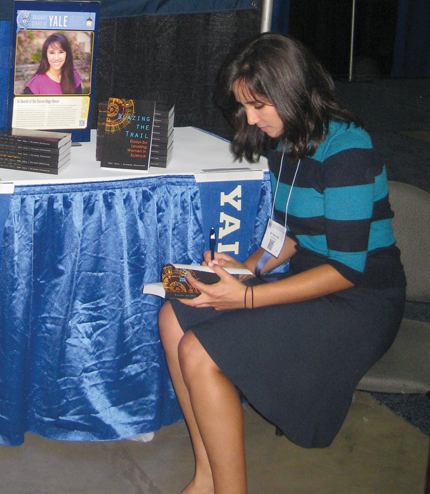

Blazing the Trail coeditor and Yale University PhD physics student Emma Ideal signs copies of the self-published book at the 2013 SACNAS conference—SACNAS is a society for the advancement of Hispanics and Native Americans in science.

So the pair decided to try self-publishing. This summer they finished their book, Blazing the Trail: Essays by Leading Women in Science, which features 35 essayists, most of them physicists. Using funds donated by their graduate physics departments, Ideal and Meharchand—who attended Michigan State University and is now a postdoc at Los Alamos National Laboratory—send out copies of their book to various science departments, science associations, and libraries. Although the writing and editing process took almost two years, Meharchand says that with a traditional publisher, the process would likely have taken even longer and the essays may have been subject to overediting. “We had control of the speed of production and control of the message,” she says.

But Audra Wolfe, a former acquisitions editor for Rutgers University Press and now an independent publishing consultant, sees only a limited role for self-publishing in science. “An effective use of self-publishing may be if you have a fairly technical book—for example, conference volumes—and you know how to reach your target audience,” she says. “But hardly any [news publication] will review a self-published book, and it won’t get you tenure. As long as scholars care about credentials, I think there will be something resembling the traditional publishing industry.”