A meticulous thermodynamic recipe for cooking eggs

DOI: 10.1063/pt.uvhf.capk

An egg with a creamy yolk and a fully set white was the result of a 32-minute periodic cooking procedure inspired by polymer engineering. (Photo courtesy of Emilia Di Lorenzo and Ernesto Di Maio.)

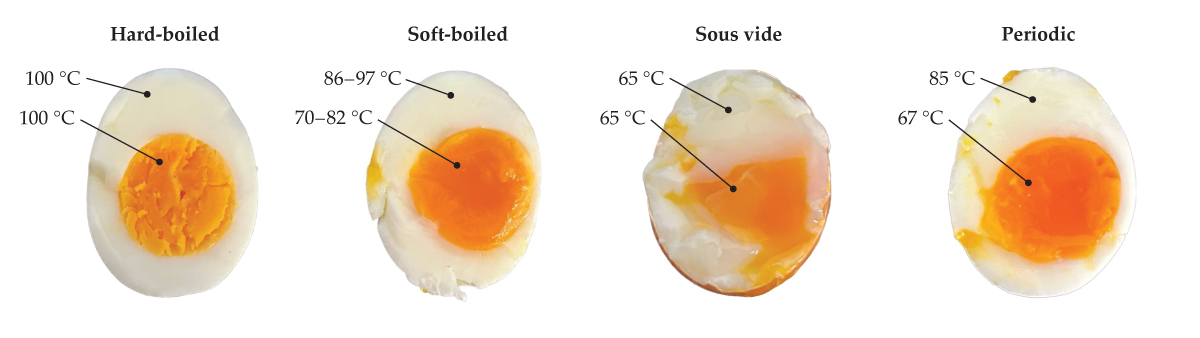

For many people, a perfectly cooked whole egg would have a yolk that is creamy and an albumen, commonly called the white of the egg, that is set. The yolk reaches a creamy texture at 65 °C, but the albumen becomes fully set at 85 °C. Common cooking methods often lead to a solid, flaky yolk (hard-boiling), a runny yolk (soft-boiling), or an unset white (sous vide, in which eggs are submerged in relatively low-temperature water).

Realizing two specific temperatures within an object is a familiar problem to Ernesto Di Maio, of the University of Naples Federico II in Italy, and his colleagues. They expose polymer foams to time-varying pressures and temperatures to induce the formation of layers with different densities or morphologies. Because eggs have both an internal boundary and foaming capacity, Di Maio asked his student Emilia Di Lorenzo to determine if similar engineering principles could be applied in the kitchen.

Guided by their previous experience, Di Maio and colleagues predicted that alternating the exterior temperature would be the best way to manipulate the interior temperature of the two egg regions in different ways. Di Lorenzo created simulations based on basic heat-transfer equations and kinetic models of gelation to refine the cooking temperatures and timing. Then, the team broke open the egg cartons.

The trick, the researchers learned, was to alternate between cooking the eggs in 100 °C and 30 °C water every two minutes, for a total of 32 minutes. The two regions of the egg respond differently to the alternating temperatures because it takes 10–100 seconds for the heat to transfer across the boundary into the yolk. The albumen oscillates in temperature, which rises and falls with each transfer between pots before it eventually settles at around 85 °C. The yolk does not respond as quickly; instead, its temperature slowly rises until it reaches 67 °C, slightly above the average of the two cooking temperatures.

Different egg-cooking methods yield different results. Hard-boiling often creates a flaky yolk; soft-boiling, a runny yolk; and sous vide, a white that isn’t fully set. Periodically switching eggs between boiling and tepid water can achieve internal temperatures that yield a creamy yolk and a fully set white. (Figure adapted from E. Di Lorenzo et al., Commun. Eng. 4, 5, 2025

Satisfied with the temperature readings, Di Maio and colleagues also found that the two regions of the periodically cooked eggs had the desired textures. Adjusting the temperature of the pots or changing the time the egg remains in each can tailor the exact outcome to accommodate personal preference in cooking. The extra time to cook might not be worth it for the average home cook, but Di Maio and Di Lorenzo—who does not even like eggs—predict that restaurants may experiment with their method. In the meantime, they have turned their attention back to multilayered polymers. (E. Di Lorenzo et al., Commun. Eng. 4, 5, 2025

This article was originally published online on 21 February 2025.