The Second Law of Thermodynamics

DOI: 10.1063/1.1995749

Ellen felt out of place welcoming people to an apartment that she herself had never set foot in until the previous day. But there was nothing to be done for it. Her brother Jake, who had visited the apartment many times over the last 10 years, was already drinking and talking too loudly and threatening to play their father’s scratchy 50s records on the old RCA machine. Dreading the music, Ellen stood on the dark landing just outside the apartment and helped people off with their heavy winter coats and scarves. Everyone was out of breath after trudging up the four flights of stairs. On the ground floor, a handwritten sign taped to the wall announced that the elevator was broken. “Wednesday” was written at the top of the sign, then crossed out and “Thursday” written beneath, which was also crossed out and “Friday” scrawled below that.

“You must be Milt’s daughter,” said a plump-faced, elderly Asian man who had just reached the landing. “Mr. Chee,” he said between gasps and held out his hand. “You have his eyes.”

“Yes. I’m Ellen.” She smiled at Mr. Chee. In the dim light, a fine perspiration softly gleamed on his bald head like a silvery veil.

“I’m sorry about your father,” said Mr. Chee, still breathing heavily and wheezing a bit. “He was a good man. An honorable man. I was proud to know him.”

“Thank you.”

“Milt talked about you. I knew you were his daughter the moment I saw you.” Mr. Chee paused a moment and rubbed his hands together, still red and cold. “Your father delivered produce on Tuesdays and Fridays to my market. You may have heard of it, maybe not. Wan Tan Market, on 25 West 23rd? He never missed a day, your father. Rain, snow, he never missed a day.” Mr. Chee hesitated. “I didn’t know he lived here.”

A wave of embarrassment washed over Ellen as she imagined what Mr. Chee and the other visitors must think about this crumbling brick building, so close to the Port Authority bus terminal that you could smell the bus exhaust. The plaster falling in chunks off the walls, the elevator that didn’t work, the shabby little apartments. Ellen had suggested to Jake that they receive visitors at his hotel, but he had taken a room for himself and his daughter at the cheapest hotel he could find, the Sherwood Arms, at $79 per night.

Mr. Chee was beginning to recover his breath. He rubbed his hands together again and patted his head with a yellow silk handkerchief. “Your father was a good man,” he whispered to Ellen. Then he touched her lightly on the shoulder, as if to comfort her, and entered the apartment.

While the door was open, Ellen glimpsed inside and saw Jake in eager conversation with Mr. and Mrs. Arnold. Mrs. Arnold, a stout woman with a limp in her left leg, was still wearing her lavender scarf. Mr. and Mrs. Arnold were old family friends. For years and years, they had owned a coffee shop in the Theater District, near the street corner where Ellen’s father performed his daily science demonstrations, Broadway and 46th, the same spot for 35 years. People on their way to the Marquis Theater or the LuntFontanne or the Plymouth would stop for five minutes and watch as Milt set off electric sparks, or heated a U-shaped glass tube and caused the liquid inside to oscillate back and forth, or made strange patterns of metallic particles with magnets. Milt was a fixture at that street corner, when he wasn’t wheeling his dolly of vegetables around town. He used to say that people in the Theater District were more intelligent than the average New Yorker.

Mr. Chee had just disappeared behind the door when a Mr. Papadopoulos arrived at the top of the stairs huffing and puffing, another small grocer who took deliveries from Ellen’s father. Looking at the floor instead of at Ellen, Mr. Papadopoulos offered his condolences. Then the music started—“Three Coins in the Fountain.”

“I know that one,” Mr. Papadopoulos said with a faint smile on his face.

“I’m sorry about the music,” said Ellen.

“No problem,” said Mr. Papadopoulos. “I like it. It reminds me of my wife.” He tipped his fedora and walked into the apartment.

As she closed the door, Ellen could smell garlic cooking in one of the apartments on the landing. The odor hung heavily in the air, which was stuffy and much too warm from the excessive heat in the building. A trickle of perspiration slid down her back. How long had she been standing here? she wondered. In another few minutes, she would go in.

A woman wearing a splendid blue velvet dress and large hoop earrings was slowly making her way up the last flight of stairs. “Is that you, Ellen?” she exclaimed. She paused, gasping for breath. “Yes, it is you. Let me look at you. How long has it been since I’ve seen you? Fifteen, sixteen years? You’re still a raging beauty, dear.” She stopped and panted. “And you’ve still got a gorgeous figure. I wish I had your figure. Even when I was young, I didn’t have your figure. You must have handsome men trying to take you to bed all the time.”

MICHAEL FRANCIS

“Susan,” said Ellen. “Thanks for coming.” She embraced Susan and kissed her, intending to kiss her cheek but landing on her sculptured eyebrow. “How are you?”

“I’m fine,” said Susan. “Double fine. But how are you? I’m so sorry about Milt. He was some piece of work, wasn’t he. But I had a soft spot for him. Your dad was one of my favorite cousins. At least he went suddenly, not like your mother.” Susan held onto the banister, still catching her breath, and smoothed out her dress. “How old are you now, Ellen?”

“Forty-five.”

“Jesus, you look good for forty-five. You look good for thirty-five.”

“How is your husband?” asked Ellen.

“You’ve been out of touch a long time,” said Susan with a grim laugh. “David and I got divorced nine years ago. I don’t know where he is, and I don’t want to know. I try not to think about him.”

Ellen fidgeted uncomfortably, feeling that she had made a mistake. She liked Susan, despite her in-your-face manner.

“I look like a mess,” said Susan. “A seventy-year-old mess.” She sighed and took a compact and lipstick out of her sequined purse and began primping. When she had finished, she handed the mirror to Ellen. “Here dear,” she said, “you’ve probably been stranded out on this stairwell for ages.”

Ellen looked at herself in the little oval mirror. She was indeed a beautiful woman, with almond shaped eyes, silky auburn hair that just touched her shoulders, fragile cheekbones that made her face seem like it was wrapped in a gift box. Only the creases around her neck showed her age. She frowned at her reflection and borrowed Susan’s brush to put her hair right. Then she adjusted the pearl necklace that her mother had given her. Earlier today, she had debated about wearing the necklace. It made her sad, but for some reason she had wanted to remember her mother these last few days.

Ellen had a sudden vision of borrowing Susan’s powder and lipstick many years ago, during one of Susan’s annual visits. Ellen must have been 12 or 13 at the time, when they lived on Bleeker. “She looks like a little goddess,” Susan had commented after Ellen was all made up. “Yes,” said Ellen’s mother approvingly. “What do you think, Milt?” Even back then, Ellen doubted that her father could ever recognize anything pretty or fine, habitually dressed in a sweatshirt and tennis shoes as he was, always unshaven, always smelling of rotten vegetables. “She’s an A-1 beauty,” her father had said, surprising her.

From the apartment, the Chordettes began singing “Mr. Sandman.” Ellen could hear Jake and some other woman singing along with the record. Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream. …

“Is your husband here?” asked Susan. “What’s his name? Lance, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Lance. Lance didn’t want to come,” said Ellen. “He never met Dad. He stayed in Cleveland.”

“I remember Henry. Do you have any contact with him?”

“No,” said Ellen. “But I think that he’s remarried.”

Susan paused, taking the news in. “Milt pretty much kept me up on you, whatever he heard from Jake. You know, he loved you.” Ellen nodded, silently praying that her second cousin wouldn’t start in on things.

Susan stood in front of the apartment door without opening it, as if waiting for something. She turned to Ellen. “I just can’t believe Milt lived in this dump.” She put her hand to her face. “I would have given him money, Ellen. I would have given him money anytime he asked. But he never asked.” Susan sighed. “Let’s go in.”

Inside the small living room, people were clustered in groups, drinking and eating. Mr. and Mrs. Arnold were talking to Tania, Jake’s 24-year-old daughter. Jake sat on the couch, red-faced, trading stories with Mr. Chee and Mr. Papadopoulos. A Mrs. Abernathy, who had called earlier in the day and who taught at Milt’s ancient high school, P.S. 79, was over by the window with Dan Henderson, the superintendent of the building, and a “Miss Ursula Elkin,” who lived in the apartment across the way. The conversations swelled in volume, then diminished, then swelled again, like waves on an ocean. Every minute or two, someone would walk over to the kitchen table, which was set up with slices of Velveeta cheese, crackers, pretzels, donuts, two quart bottles of Wild Turkey bourbon, and three bottles of white wine.

Ellen found her hands shaking. Who were these strangers in her father’s apartment? She didn’t know who to talk to or what to talk about, so she sat in the fabric-covered chair next to the closet, a chair she remembered from Bleeker Street.

It was a tiny apartment, barely large enough to hold 10 people. The day before, Ellen had gone through it all, the whole jumbled mess—the living room, the efficiency kitchen, the bathroom, the two closets, her father’s little bedroom with its bare mattress. It had been wrenching and strange to see where her father lived all those years, the rooms he lived in, the chairs he sat in, the food he ate still in the refrigerator. Tears came to her eyes. In one of the drawers, she found her father’s old stopwatch with the nicks on the casing. Holding it in her hand, she had remembered a morning centuries ago when he asked her to time the swing of a pendulum while he called out the start and the stop.

Having taken off her scarf now and had some wine, Mrs. Arnold was talking about Ellen’s mother, Lavinia. In the background, Fats Domino sang “Blueberry Hill.” “Lavinia was an amazing woman,” Mrs. Arnold said and sipped her white wine. “She was always reading some new book about something or the other. She knew everything there was to know about Malaysia. I don’t even know where Malaysia is. What a tragedy that she died so young. How old was she?”

“Forty,” said Jake from the couch. “She died two weeks after her 40th birthday.”

“I remember her like I saw her yesterday,” said Mrs. Arnold. “Lavinia was the most clever woman I ever knew. Do you know what she did once? She found an accounting error in our books for the shop. Can you believe that? She was over at the apartment one day and the books were lying on the table and she just happened to glance at them, you know, the way you would glance at a magazine, and she spotted an error. She was one smart woman. Lavinia could have done anything in the world if she’d lived a natural life span.”

“No she couldn’t,” said Ellen quietly. “Dad wouldn’t let her work. Dad hardly let her out of the house.”

Mrs. Arnold took another sip of her wine. Now the others had stopped their own conversations and were listening. “You’re being too hard on him,” said Mrs. Arnold.

“He wouldn’t let her out of the house,” said Ellen. “Mom wanted to get out of the house. She wanted to work. But Dad wouldn’t let her. He was afraid she would cheat on him, or something like that. One time she applied for a job at a business office, and when she came home he slapped her.” Ellen let her head loll back on her chair. “God knows we could have used the money. But that wasn’t the main thing. Mom just wanted to see the world.”

“That doesn’t sound like Milt,” said Mrs. Arnold. She glanced over at her husband for confirmation, but he only stared at her blankly, bewildered.

“That was him,” said Ellen. “Mom just never complained to anybody about it.” Ellen didn’t know why she had just said what she said. It was true, but she shouldn’t have said it, not now.

“Well.” Mrs. Arnold hesitated, as if not knowing how to remedy the awkward moment. She looked down in her lap and then up again. “I want everyone to know that every Monday morning for the last couple of years, Milt went over to my daughter’s apartment and took care of her little boy. It’s not like a man to do that. Milt had a sweetness.”

“Amen,” said Mr. Henderson, the super.

For a few moments, no one spoke. “I’ll miss him,” said Jake. He stood up from the couch, swaying. “I’m getting myself another drink. Anybody need anything?”

Ellen stood by the one window, gazing out. The view wasn’t much. Far below, she could see an alley with a broken bed frame lying in it. Directly across the way was another apartment building, its rows of windows flickering with blue light from the televisions inside, the silhouettes of laundry hanging from the metal railing of each small balcony. Horns honked on the street below.

Someone put on “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley. “Did you ever see Milt perform one of his science demonstrations?” Mrs. Arnold asked Susan, almost shouting to be heard over the music.

“No,” answered Susan. “I never had the pleasure.”

“They thought he was a magician. I remember once, it must have been 15 years ago now, a little girl was positive that Milt had something up his sleeve. She asked him to take off his shirt, can you believe it? And he did. It was winter time, like now, but he took off his coat and his shirt and stood there shivering while he did his experiment, or whatever it was. The little girl was laughing, and he was laughing.”

In her mind, Ellen remembered one of her visits to the corner of Broadway and 46th to say hello to her father. She was on the way to a friend’s apartment after school, somewhere in the west 50s. Several people were gathered around her father as he did one of his experiments, something with glass rods and a stream of water. Above his head, a banner fluttered from a building. Paper coffee cups and pamphlets littered the sidewalk. Her father looked like a homeless man, an organ grinder. People tossed quarters at him, at her father. Coins rolled on the pavement. Before he could see her, Ellen fled, ran down one street, then another, then another; she wanted to be swallowed by the great jeering mouth of the city, she wanted to be lost, she wanted to drown, she wanted never to go back to that corner where her father was a fool.

“I’ll tell you something about Milt that I’ll bet nobody knows,” said Miss Ursula Elkin. Ellen had never met Miss Ursula Elkin until today. She looked to be in her late sixties and wore bright red lipstick and a bright red boa slung around her neck. “I live in that apartment right there,” she said and walked to the window. She pointed to an apartment window straight across in the neighboring building, less than twenty feet away. “Right there. Almost every night, I could see Milt sitting at this table, writing away. I don’t know what he was writing, but it must have been something fantabulous because he was at it every night, sometimes four or five hours straight. And while he was writing, he would sing. Yep. You could hear him. He loved the old 50s songs. ‘Rock Around the Clock.’ ‘Young at Heart,’ by Frank Sinatra. ‘Bye Bye Love.’ That was the Everly Brothers if I’m not mistaken. ‘Blueberry Hill.’ “ At that point, Miss Ursula Elkin began singing “Young at Heart” herself.

MICHAEL FRANCIS

“I know what he was writing,” said Jake, now so drunk that he could barely stand and had to lean against the kitchen counter. “He was doing math about The Second Law of Thermodynamics.”

“I’ll be,” said Miss Ursula Elkin. “I had a feeling that he was some kind of genius.”

“Dad was totally bonkers about The Second Law of Thermodynamics. Allow me to explain, ladies and gentlemen. The Second Law of Thermodynamics says that everything is slowly going to hell in a handbasket. Nothing more, nothing less.” Jake was slurring his words, so that Mr. Papadopoulos had to ask him to repeat.

“I knew that,” said Miss Ursula Elkin. “I knew that everything is going to hell. So that’s what it was he was working on.” She gave her boa a shake.

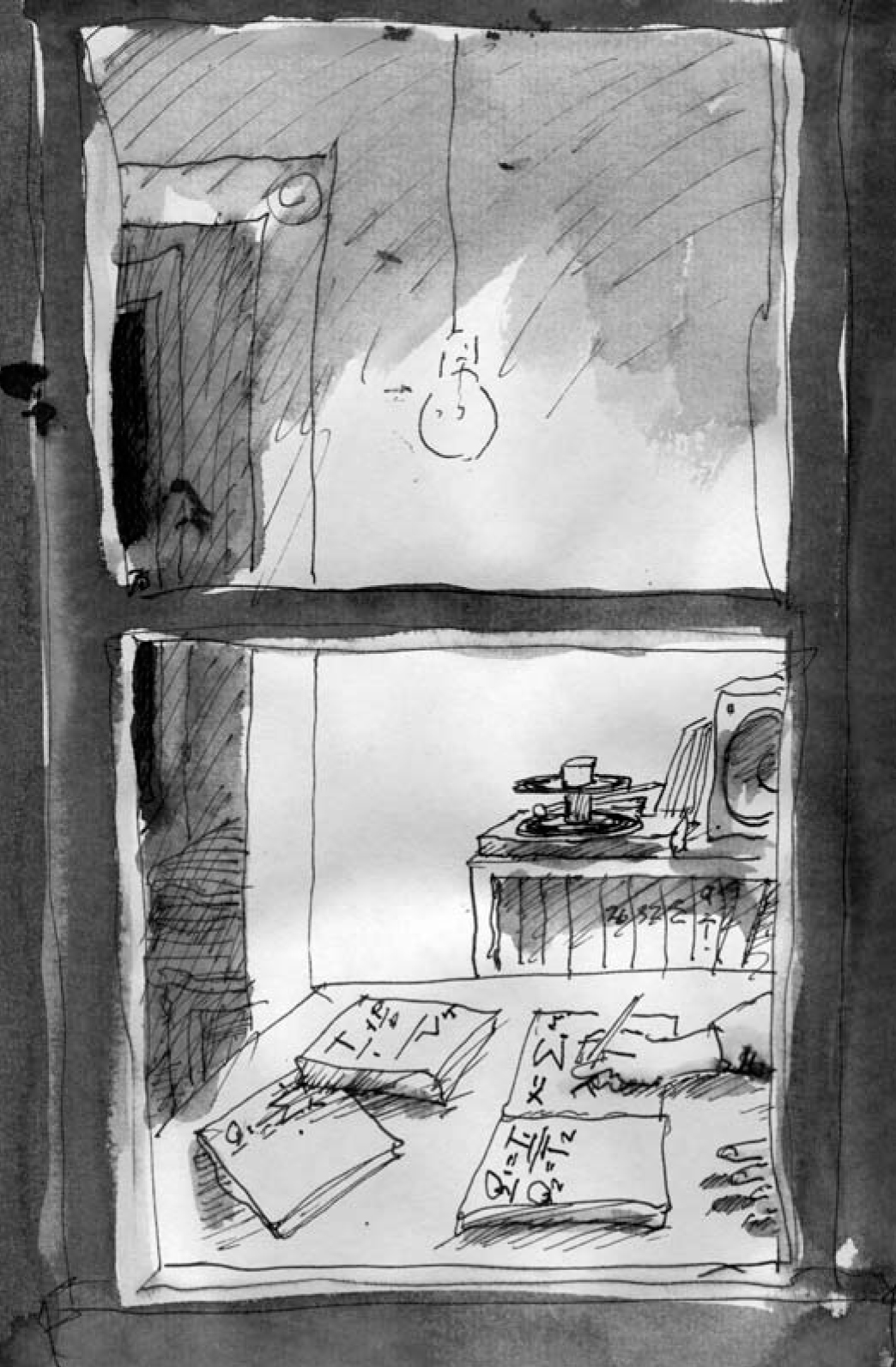

“Dad loved to collect data on things running down,” said Jake. “Day Tah. You know, toaster ovens burning out. Springs losing their spring. New holes in his sweatshirts. He loved the stuff. And he put it in math equations. Zillions of equations. He had one science course in high school, and that’s all it took. He made ten or eleven notebooks of equations about The Second Law of Thermodynamics. That was his life’s work. Dad started making those notebooks when I was ten or twelve years old. Do you remember, El?”

“Yes,” said Ellen. She was beginning to feel sick to her stomach, that familiar sensation of being back in her father’s crazy world.

Jake filled his glass again with the Wild Turkey. “Dad said the whole country had been falling apart since the middle 1950s. The whole friggin country. It was some great cosmotological example of The Second Law of Thermodynamics.”

“I’ll be a goddamn fish,” said Miss Ursula Elkin.

“Milt was some piece of work,” said Susan.

“I think old Milt had a point,” said Mr. Henderson, the super. A fiftyish man with a pock-marked face oddly enhanced by a delicate moustache, he had been making eyes at Tania for some time and now gave her a knowing look. “All people care about in this country is money. The U. S. of A. is going to hell.”

“America is a great country,” said Mr. Chee. “This is where I found my fortune.”

“Money, money, money,” said Mr. Henderson.

“Things aren’t what they used to be,” said Mr. Papadopoulos. “I’m in the Garment Center. When I started my store in the 1960s, the whole area was empty. Now, there’s wall-to-wall people. You got your health clubs and your spas and your department stores three blocks long. You can’t breathe.”

“You couldn’t ever breathe in New York,” said Mr. Henderson. “But I tell you, now it’s all about money.”

“Those notebooks are here somewhere,” said Jake. “Where are they?” He staggered around the living room, looking inside the two tables, in the closet, under the couch. When he couldn’t find them, he went into the bedroom. They could hear drawers opening and closing. “Where are those things,” yelled Jake. “Those notebooks were here yesterday morning. I saw them. Did you see them, El? They were blue things.”

“I may have thrown them out,” said Ellen. “I’m not sure. I threw out a lot of stuff yesterday. The place was a rat’s nest.”

“How could you have done that,” shrieked Miss Ursula Elkin. “We should look for them. Where did you throw them out? Did you put them in the green garbage cans on the first floor? We could go down there and look. We should all go down there.”

“I can’t remember,” said Ellen. She poured herself a Wild Turkey and sat down on the couch. “I can’t believe Dad spent his nights doing that stuff,” she said softly. She took a long drink. “Yeah. I can believe it. He probably thought he was making some great discovery.” She took another drink.

Tania sat on the couch next to Ellen. “Could we talk a little, Aunt Ellen?” she whispered.

“Sure,” said Ellen. She had always been fond of Tania. Now, she saw how lovely her niece had become, with clear blue eyes and smooth creamy skin. And Tania was wearing her grandmother’s gold earrings, which Ellen remembered well.

“I’ve got a guy,” said Tania, still whispering and smiling. “His name is Nick. He’s got a good job in a shipping company. I’m so glad I can talk to you.”

“I’m glad too,” said Ellen. “I’m happy for you.”

“Nick is really sweet to me,” said Tania. “But he’s more than sweet. He respects me. And he’s got a good job and all.” Tania turned around on the couch, so that her back was to her father. “We want to get married,” she whispered. “Would you mention it to my dad? I don’t think he likes Nick.”

“I’ll talk to Jake,” said Ellen. “Do you love Nick?”

“I love him more than anything,” said Tania. Her eyes were shining now. “I’ve seen pictures of you when you were my age. You were really beautiful. Not that you aren’t beautiful now. I think I’ve inherited a little of your looks. Not a lot, but a little. Nick saw the pictures of you and said so.” Ellen squeezed Tania’s hand and smiled at her. “It must have taken so much guts to leave home when you did,” said Tania, “when you went to Los Angeles, I mean. What was it like, being on your own?”

“Oh, it was wonderful,” said Ellen, remembering the sticky June day that she walked out of her Bleeker Street apartment for the last time, four years of trying to live with her crazy father after her mother had died, like being trapped in a box underwater, and then the vastness of outer space. As she was leaving, her father had stood there and said, “You’ll be back. I know you’ll be back,” and she had thought to herself that she would never be back. Ellen turned to look at Tania and noticed how delicate her hands were. She could be a dancer with hands like that.

“I worked in a bank,” Ellen continued. “It was wonderful for a while. At night, I used to go to some of the bars. Not the sleazy bars but the nice ones. I made this little game with myself that I was going to try every kind of drink.” She laughed. “I was only nineteen. I met a lot of guys. Most of them creeps.”

“And when did you meet Henry?”

“Let me think. That was quite a while later. Henry worked at the bank. He was better to me than most of the guys I was dating, and he had this great way of telling funny stories, so I married him. He turned out to be a creep too.” Ellen took a swallow of her bourbon. “I got sick, and he left me, and we got divorced.”

“I met Henry once. Do you remember? We were all together at a restaurant in Philadelphia for Jake’s birthday. I never met Lance.”

“Nobody’s met Lance, and he intends to keep it that way.”

“Things good between you and Lance?”

“Sure,” said Ellen. “Things are OK. Lance didn’t want to come to Dad’s funeral so he stayed in Cleveland.”

“I want you to meet Nick. He told me he’d like to have three children. Can you imagine? But I can’t think about children now. I want to finish school.”

“Smart girl,” said Ellen. She leaned over and kissed Tania on the cheek. “And I’ll talk to your father.”

They both looked over at Jake, who was slumped in a corner with his eyes closed. “I think I’m going to leave now,” said Tania.

“You don’t want to wait for Jake?”

“No, I want to leave now. I can get to the hotel myself. Goodnight, Aunt Ellen. Thank you for what you said.” Tania got her coat and left quickly, without saying goodbye to anyone else.

Ellen stood up, stretched, and went to the kitchen. The two bottles of bourbon were almost empty. Next to the toaster, she recognized the photograph of Milt’s brother Harry, killed as a young man in the Korean War. Ellen remembered the picture from the house on Bleeker. She looked at it again for a few moments, thinking how handsome Harry looked in his crisp US Navy uniform. She was beginning to feel very tired from the bourbon and the long day. It was after midnight.

“Where’s everyone spending the night?” asked Mrs. Arnold. She stood near the door, holding her coat. Beside her was her husband, who had said nothing during the evening. “We’ve got a guest room in our apartment.”

“I’m at the Lincoln Hotel,” said Susan. “I always stay there. But thanks for the offer.”

“Jake and Ellen? Jake, can you hear me?”

“Tania and I are taken care of,” muttered Jake without opening his eyes.

“Where’s Tania?”

“She left already,” said Ellen.

“And you Ellen?”

“I thought I would try staying here.”

“Well then, everyone is OK,” said Mrs. Arnold. “We’ll be off then.”

She paused. “Milt was very dear to us. He had a good heart.” Then, unexpectedly, Mrs. Arnold began crying. She stood near the door for a few moments crying quietly and then left with her husband.

“It’s time for me to go as well,” said Susan.

“Me too,” said Mr. Henderson, who had sat drinking by himself since Tania left.

“I’m about to flop myself into bed,” said Miss Ursula Elkin. “I’m going to miss seeing Milt writing away on his math. And I’m going to miss him singing. You know, I could hear him singing all the way over at my apartment. I’m going to miss those 50s songs he sang.” She shook her head sadly.

“Where are those friggin notebooks?” Jake managed to groan. “They were here yesterday.”

“It’s a pity,” said Miss Ursula Elkin. She took a long look around the room, as if trying to remember exactly where each person had been sitting, and left.

MICHAEL FRANCIS

Now, everyone was gone, except Jake and Ellen. Jake had moved to the couch, where he was curled up in a fetal position. From beyond the door, Ellen could hear the last of the departing footsteps, faintly tapping on the stone stairs. She turned off the two lamps, leaving the room dimly lit by a small light in the kitchen. The two empty bourbon bottles cast fantastic curvy shadows on the wall, like dancers doing some strange dance.

For some time, Ellen sat in a chair across from the couch, listening to Jake’s heavy breathing. Jake stirred and opened his eyes, looked around the room and saw Ellen, and then closed his eyes again. “That wasn’t much fun,” he said softly, slurring his words.

“No.”

“Well, I guess I should get up and get over to the Sherwood Arms.”

“Don’t be silly, Jake. You just stay where you are. You can sleep on the couch. Tania will be fine by herself.”

Jake stretched his legs out. “Where will you sleep, El?”

“I’ll sleep in Dad’s bed.”

Jake let out a long sigh. “It’s just us now, isn’t it. Dad’s gone. I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it.” He shifted on the couch, his eyes still closed. “We didn’t amount to much, did we, El. That’s the way it goes.”

“You get a good sleep,” said Ellen.

“Yeah,” he said. Within seconds, he was snoring. Ellen stood by the couch watching him for a few moments. Then she took off his shoes and put a pillow under his head.

In her father’s small bedroom, she undressed. When she couldn’t find any sheets, she covered the mattress with towels. Somewhere, a clock was ticking. Tick. Tick. Tick. The sound throbbed in her brain. Her body felt completely rung out. She needed to sleep. She would sleep until noon. Perhaps she would sleep for a week. She lay down and closed her eyes. Stretching out on the bed, she became aware of something bumpy under the mattress, a small lump but definitely something, making her even more uncomfortable. Tick. Tick. Grudgingly, she pulled herself up and lifted the mattress. There she found a blue notebook. “Oh God,” she said to herself. What should she do with it? Tomorrow, she would give it to Miss Ursula Elkin. Absently, she flipped open the notebook to a random page. It was filled with neat lines of numbers and mathematical symbols, gibberish to her. But in the margins, her father had written some words. “I’m on the verge!!!” one sentence read. “Everything is here,” said another. “Perfection.”

Ellen read the words again and slowly traced over the familiar handwriting with her finger. She imagined her father writing those words late at night, sitting at his desk in the low light of a lamp, singing while he worked on The Second Law of Thermodynamics. And at that moment, she realized that he had always had what she never had—happiness. Her father had lived a life. Ellen let the notebook drop to the floor.

Weak with exhaustion, she fell back on the bed. Jake had been right. She had not amounted to much. And she was no longer young. Soon, her looks would be gone, and then she would have nothing. How had it all happened, the years? The years were so small. Tomorrow, she would need to make final arrangements for the funeral. She would have to decide about the flowers and the music and whether to rent a car. She would have to ask Susan for money. And then the trip back to Cleveland, her receptionist job at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the four rooms of her empty house. Now her head was pounding. For a while, she lay staring at the ceiling. Then she leaned over and picked up her father’s notebook and put it beside her on the bed. She would keep it herself. She would keep it, she thought, while the clock ticked and ticked and Jake in the next room turned in his dreamless sleep.▪