The Privilege of Being a Physicist

DOI: 10.1063/1.1564349

Editor’s Note: Over the decades, Victor Weisskopf (1908–2002) was a great friend of this magazine. He contributed no fewer than 10 feature articles, as well as letters, book reviews, opinion columns, and more. The following article, reprinted from the August 1969 issue of Physics Today, captures much of Viki’s love of physics and breadth of thought. This and others of his past contributions to the magazine can be found at http://www.physicstoday.org

There are certain obvious privileges that a physicist enjoys in our society. He is reasonably paid; he is given instruments, laboratories, complicated and expensive machines, and he is asked not to make money with these tools, like most other people, but to spend money. Furthermore, he is supposed to do what he himself finds most interesting, and he accounts for what he spends to the money givers in the form of progress reports and scientific papers that are much too specialized to be understood or evaluated by those who give the money—the federal authorities and, in the last analysis, the taxpayer. Still, we believe that the pursuit of science by the physicist is important and should be supported by the public. In order to prove this point, we will have to look deeper into the question of the relevance of science to society as a whole. We will not restrict ourselves to physics only; we will consider the relevance of all the natural sciences, but we will focus our attention on basic sciences, that is, to those scientific activities that are performed without a clear practical application in mind.

The question of the relevance of scientific research is particularly important today, when society is confronted with a number of immediate, urgent problems. The world is facing threats of nuclear war, the dangers of overpopulation, of a world famine, mounting social and racial conflicts, and the destruction of our natural environment by the byproducts of ever-increasing applications of technology. Can we afford to continue scientific research in view of these problems?

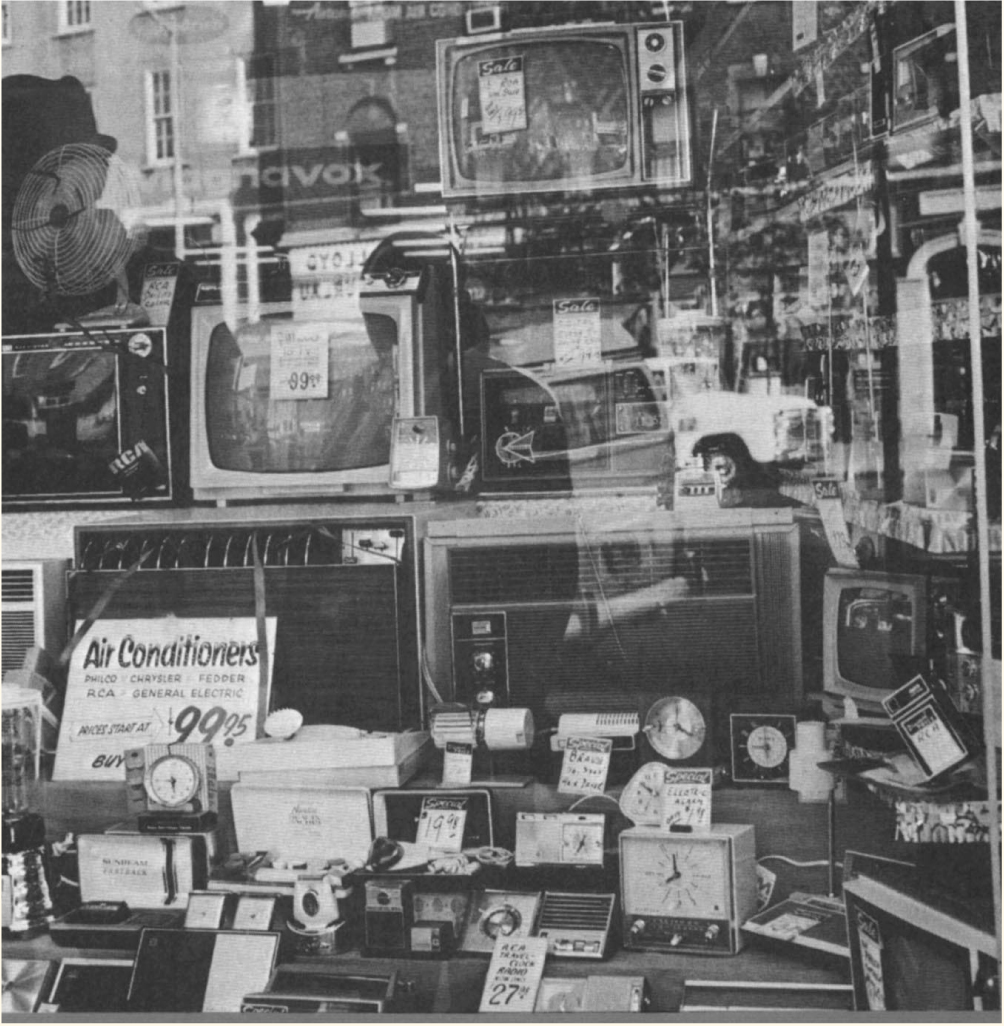

“… the destruction of our natural environment by the byproducts of ever-increasing applications of technology.”

I will try to answer this question affirmatively. It will be the trend of my comments to emphasize the diversity in the relations between science and society; there are many sides and many aspects, each of different character, but of equal importance. We can divide these aspects into two distinct groups. On the one hand, science is important in shaping our physical environment; on the other, in shaping our mental environment. The first refers to the influence of science on technology, the second to the influence on philosophy, on our way of thinking.

Technology

The importance of science as a basis of technology is commonplace. Obviously, knowledge as to how nature works can be used to obtain power over nature. Knowledge acquired by basic science yielded a vast technical return. There is not a single industry today that does not make use of the results of atomic physics or of modern chemistry. The vastness of the return is illustrated by the fact that the total cost of all basic research, from Archimedes to the present, is less than the value of ten days of the world’s present industrial production.

“There is not a single industry today that does not make use of the results of atomic physics or of modern chemistry.”

We are very much aware today of some of the detrimental effects of the ever-increasing pace of technological development. These effects begin to encroach upon us in environmental pollution of all kinds, in mounting social tensions caused by the stresses and dislocations of a fast-changing way of life and, last but not least, in the use of modern technology to invent and construct more and more powerful weapons of destruction.

In many instances, scientific knowledge has been and should continue to be applied to counteract these effects. Certainly, physics and chemistry are useful to combat many forms of pollution and to improve public transportation. Biological research could and must be used to find more effective means of birth control and new methods to increase our food resources. It has been pointed out many times that our exploitation of the sea for food gathering is still in the hunting stage; we have not yet reached the Neolithic age of agriculture and animal breeding in relation to the oceans.

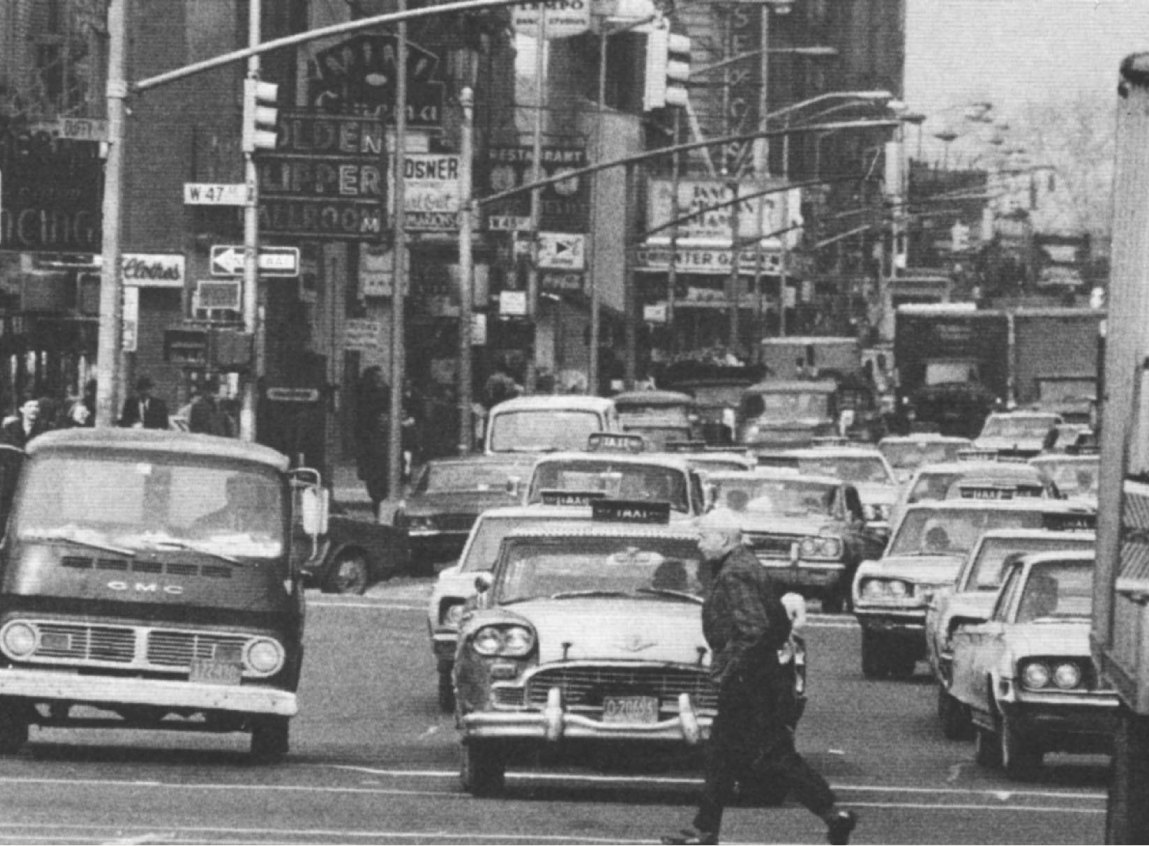

Many of the problems that technology has created cannot be solved by natural science. They are social and political problems, dealing with the behavior of man in complicated and rapidly evolving situations. In particular, the questions arise: “What technical possibilities should or should not be realized? How far should they be developed?” A systematic investigation of the positive and negative social effects of technical innovations is necessary. But it is only partly a problem for natural sciences; to a greater extent, it is a problem of human behavior and human reaction. I am thinking here of the supersonic transport, of space travel, of the effects of the steadily increasing automobile traffic and again, last but not least, of the effects of the development of weapons of mass destruction.

“Many of the problems that technology has created cannot be solved by natural science. They are social and political problems, dealing with the behavior of man in complicated and rapidly evolving situations.”

Physical environment

What role does basic science have in shaping our physical environment? It is often said that modern basic physical science is so advanced that its problems have little to do with our terrestrial environment. It is interested in nuclear and subnuclear phenomena and in the physics of extreme temperatures. These are objectives relating to cosmic environments, far away from our own lives. Hence, the problems are not relevant for society; they are too far removed; they are studied for pure curiosity only. We will return later to the value of pure curiosity.

Let us first discuss how human environment is defined. Ten thousand years ago, metals were not part of human environment; pure metals are found only very rarely on Earth. When man started to produce them, they were first considered as most esoteric and irrelevant materials and were used only for decoration purposes during thousands of years. Now they are an essential part of our environment. Electricity went through the same development, only much faster. It is observed naturally only in a few freak phenomena, such as lightning or friction electricity, but today it is an essential feature of our lives.

This shift from periphery to center was most dramatically exhibited in nuclear physics. Nuclear phenomena are certainly far removed from our terrestrial world. Their place in nature is found rather in the center of stars or of exploding supernovae, apart from a few naturally radioactive materials, which are the last embers of the cosmic explosion in which terrestrial matter was formed. This is why Ernest Rutherford remarked in 1927, “Anyone who expects a source of power from transformations of atoms is talking moonshine.” It is indeed a remarkable feat to recreate cosmic phenomena on Earth as we do with our accelerators and reactors, a fact often overlooked by the layman, who is more impressed by rocket trips to the Moon. That these cosmic processes can be used for destructive as for constructive purposes is more proof of their relevance in our environment. Even phenomena as far removed from daily life as those discovered by high-energy physicists may some day be of technical significance. Mesons and hyperons are odd and rare particles today, but they have interactions with ordinary matter. Who knows what these interactions may be used for at the end of this century? Scientific research not only investigates our natural environment, it also creates new artificial environments, which play an ever-increasing role in our lives.

Mental environment

The second and most important aspect of the relevance of science is its influence on our thinking, its shaping of our mental environment. One frequently hears the following views as to the effect of science on our thought: “Science is materialistic, it reduces all human experience to material processes, it undermines moral, ethical, and aesthetic values because it does not recognize them, as they cannot be expressed in numbers. The world of nature is dehumanized, relativized; there are no absolutes any more; nature is regarded as an abstract formula; things and objects are nothing but vibrations of an abstract mathematical concept. …” (Science is accused at the same time of being materialistic and of negating matter.)

Actually science gives us a unified, rational view of nature; it is an eminently successful search for fundamental laws with universal validity; it is an unfolding of the basic processes and principles from which all natural happenings are derived, a search for the absolutes, for the invariants that govern natural processes. It finds law and order—if I am permitted to use that expression in this context—in a seemingly arbitrary flow of events. There is a great fascination in recognizing the essential features of nature’s structure, and a great intellectual beauty in the compact and all-embracing formulation of a physical law. Science is a search for meaning in what is going on in the natural world, in the history of the universe, its beginnings and its possible future.

Public awareness

These growing insights into the workings of nature are not only open to the scientific expert, they are also relevant to the nonscientist. Science did create an awareness among people of all ways of life that universal natural laws exist, that the universe is not run by magic, that we are not at the mercy of a capricious universe, that the structure of matter is largely known, that life has developed slowly from inorganic matter by evolution in a period of several thousand million years, that this evolution is a unique experiment of Nature here on Earth, which leaves us humans with a responsibility not to spoil it. Certainly the ideas of cosmology, biology, paleontology, and anthropology changed the ideas of the average man with respect to future and past. The concept of an unchanging world or a world subject to arbitrary cycles of changes is replaced by a world that continuously develops from more primitive to more sophisticated organization.

Although there is a general awareness of the public in all these aspects of science, much more could be and must be done to bring the fundamental ideas nearer to the intelligent layman. Popularization of science should be one of the prime duties of a scientist and not a secondary one as it is now. A much closer collaboration of scientists and science writers is necessary. Seminars, summer schools, and direct participation in research should be the rule for science writers, in order to obtain a free and informal contact of minds between science reporters and scientists on an equal level, instead of an undirected flow of undigested information.

Education

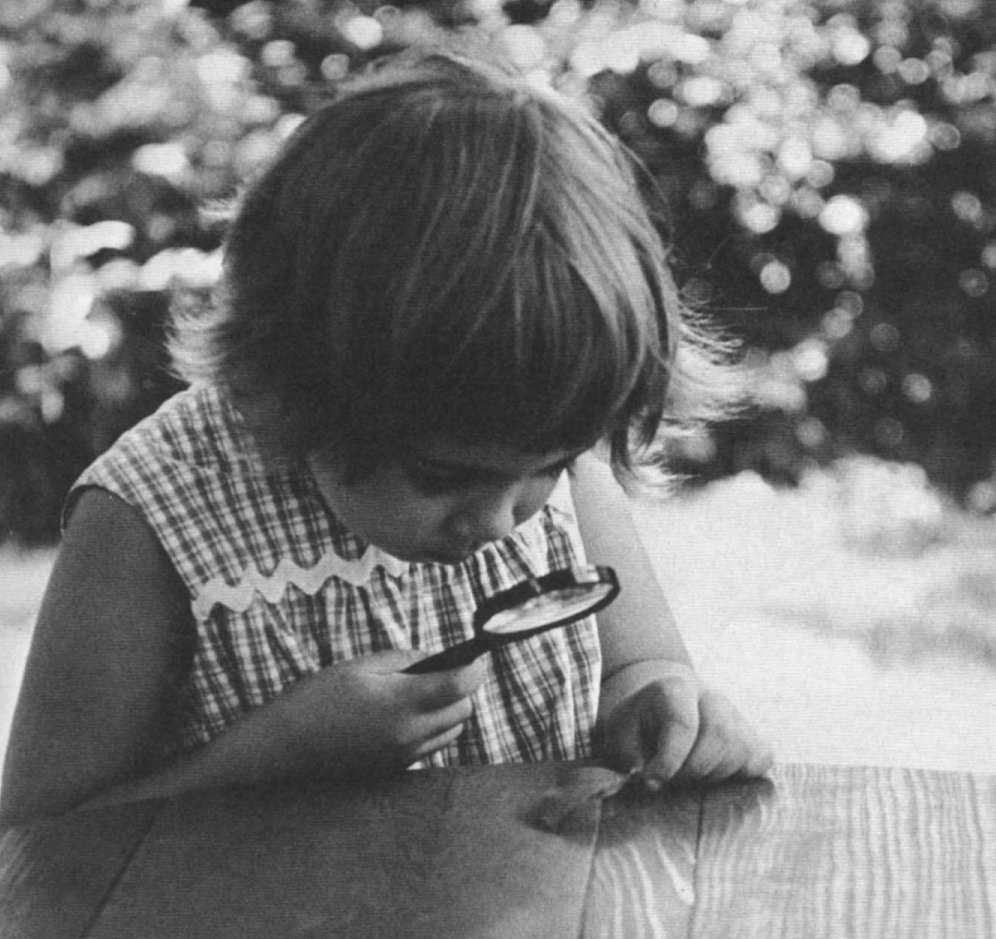

Science also shapes our thinking by means of its role in education. The study of open scientific frontiers where unsolved fundamental problems are faced is, and should be, a part of higher education. It fosters a spirit of inquiry; it lets the student participate in the joy of a new insight, in the inspiration of new understanding. The questioning of routine methods, the search for new and untried ways to accomplish things, are important elements to bring to any problem, be it one of science or otherwise. Basic research must be an essential part of higher education. In elementary education, too, science should and does play an increasing role. Intelligent play with simple, natural phenomena, the joys of discovery of unexpected experiences, are much better ways of learning to think than any teaching by rote.

“Intelligent play with simple, natural phenomena, the joys of discovery of unexpected experiences, are much better ways of learning to think than any teaching by rote.”

A universal language …

The international aspect of science should not be forgotten as an important part of its influence on our mental environment. Science is a truly human concern; its concepts and its language are the same for all human beings. It transcends any cultural and political boundaries. Scientists understand each other immediately when they talk about their scientific problems, and it is thus easier for them to speak to each other on political or cultural questions and problems about which they may have divergent opinions. The scientific community serves as a bridge across boundaries, as a spearhead of international understanding.

As an example, we quote the Pugwash meetings, where scientists from the East and West met and tried to clarify some of the divergences regarding political questions that are connected with science and technology. These meetings have contributed to a few steps that were taken toward peace, such as the stopping of bomb tests, and they prepared the ground for more rational discussions of arms control. Another example is the western European laboratory for nuclear research in Geneva—CERN—in which 12 nations collaborate successfully in running a most active center for fundamental research. They have created a working model of the United States of Europe as far as high-energy physics is concerned. It is significant that this laboratory has very close ties with the laboratories in the east European countries; CERN is also equipping and participating in experiments carried out together with Russian physicists at the new giant accelerator in Serpukhov near Moscow.

… Occasionally inadequate

The influence of science on our thinking is not always favorable. There are dangers stemming from an uncritical application of a method of thinking, so incredibly successful in natural science, to problems for which this method is inadequate. The great success of the quantitative approach in the exploration of nature may well lead to an over-stressing of this method to other problems. A remark by M. Fierz in Zürich is incisive: He said that science illuminates part of our experience with such glaring intensity that the rest remains in even deeper darkness. The part in darkness has to do with the irrational and the affective in human behavior, the realm of the emotional, the instinctive world. There are aspects of human experience to which the methods of natural science are not applicable. Seen within the framework of that science, these phenomena exhibit a degree of instability, a multidimensionality for which our present scientific thinking is inadequate and, if applied, may become dangerously misleading.

Deep involvement, deep concern

The foregoing should have served to illustrate the multilateral character of science in its relation to society. The numerous and widely differing aspects of relevance emphasize the central position of science in our civilization. Here we find a real privilege of being a scientist. He is in the midst of things; his work is deeply involved in what happens in our time. This is why it is also his privilege to be deeply concerned with the involvement of science in the events of the day.

In most instances he cannot avoid being drawn in one form or another into the decision-making process regarding the applications of science, be it on the military or on the industrial scene. He may have to help, to advise, or to protest, whatever the case may be. There are different ways in which the scientist will get involved in public affairs: he may address himself to the public when he feels that science has been misused or falsely applied; he may work with his government on the manner of application of scientific results to military or social problems.

In all these activities he will be involved with controversies that are not purely scientific but political. In facing such problems and dilemmas, he will miss the sense of agreement that prevails in scientific discussions, where there is an unspoken understanding of the criteria of truth and falsehood even in the most heated controversies. Mistakes in science can easily be corrected; mistakes in public life are much harder to undo because of the highly unstable and nonlinear character of human relations.

How much emphasis?

Let us return to the different aspects of relevance in science. In times past, the emphasis has often shifted from one aspect to the other. For example, at the end of the last century [the 19th] there was a strong overemphasis on the practical application of science in the US. Henry A. Rowland, who was the first president of the American Physical Society, fought very hard against the underemphasis of science, as is seen in the following quotation from his address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1883:

American science is a thing of the future, and not of the present or past; and the proper course of one in my position is to consider what must be done to create a science of physics in this country, rather than to call telegraphs, electric lights, and such conveniences by the name of science. I do not wish to underrate the value of all these things; the progress of the world depends on them, and he is to be honored who cultivates them successfully. So also the cook, who invents a new and palatable dish for the table, benefits the world to a certain degree; yet we do not signify him by the name of a chemist. And yet it is not an uncommon thing, especially in American newspapers, to have the applications of science confounded with pure science; and some obscure character who steals the ideas of some great mind of the past, and enriches himself by the application of the same to domestic uses, is often lauded above the great originator of the idea, who might have worked out hundreds of such applications, had his mind possessed the necessary element of vulgarity.

Rowland did succeed in his aim, although posthumously. He should have lived to see the US as the leading country in basic science for the last four decades. His statement—notwithstanding its forceful prose—appears to us today inordinately strong in its contempt of the applied physicists. The great success of this country in basic science derives to a large extent from the close cooperation of basic science with applied science. This close relation—often within the same person—provided tools of high quality, without which many fundamental discoveries could not have been made. There was a healthy equilibrium between basic and applied science during the last decades and thus also between the different aspects of the relevance of science.

Lately, however, the emphasis is changing again. There is a trend among the public, and also among scientists, away from basic science toward the application of science to immediate problems and technological shortcomings revealed by the crisis of the day. Basic science is considered to be a luxury by the public; many students and researchers feel restless in pursuing science for its own sake.

Perspective

The feeling that something should be done about the pressing social needs is very healthy. “We are in the midst of things,” and scientists must face their responsibilities by using their knowledge and influence to rectify the detrimental effects of the misuse of science and technology. But we must not lose our perspective in respect to other aspects of science. We have built this great edifice of knowledge; let us not neglect it during a time of crisis. The scientist who today devotes his time to the solution of our social and environmental problems does an important job. But so does his colleague who goes on in the pursuit of basic science. We need basic science not only for the solution of practical problems but also to keep alive the spirit of this great human endeavor. If our students are no longer attracted by the sheer interest and excitement of the subject, we were delinquent in our duty as teachers. We must make this world into a decent and livable world, but we also must create values and ideas for people to live and to strive for. Arts and sciences must not be neglected in times of crisis; on the contrary, more weight should be given to the creation of aims and values. It is a great human value to study the world in which we live and to broaden the horizon of knowledge.

These are the privileges of being a scientist: We are participating in a most exhilarating enterprise right at the center of our culture. What we do is essential in shaping our physical and mental environment. We, therefore, carry a responsibility to take part in the improvement of the human lot and to be concerned about the consequences of our ideas and their applications. This burden makes our lives difficult and complicated and puts us in the midst of social and political life and strife.

But there are compensations. We are all working for a common and well defined aim: to get more insight into the workings of nature. It is a constructive endeavor, where we build upon the achievements of the past; we improve but never destroy the ideas of our predecessors.

This is why we are perhaps less prone to the feeling of aimlessness and instability that is observed in so many segments of our society. The growing insight into nature is not only a source of satisfaction for us, it also gives our lives a deeper meaning. We are a “happy breed of men” in a world of uncertainty and bewilderment.

This article was adapted from an [after-dinner banquet] address given [on 5 February 1969] at the joint annual meeting of the American Physical Society and the American Association of Physics Teachers. I am grateful to Isidor I. Rabi for drawing my attention to Henry Rowland’s address.

More about the authors

Victor F. Weisskopf, Physics Today .