The German Physical Society Under National Socialism

DOI: 10.1063/1.1878335

The German Physical Society (DPG), founded in 1845, was at the forefront of physics research in 1933 when the National Socialists came to power. But the society and its members had already begun to feel the impact from Germany’s political and racial tensions.

The most famous émigré physicist from National Socialist Germany was certainly Albert Einstein, who had clashed with anti-Semites and conservative physicists in Germany even before 1933. When Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists came to power in January of that year, Einstein was out of the country and never returned. Einstein’s subsequent outspoken criticism of National Socialist policies—such as the racist and political purge of the universities and state research centers in April 1933—provoked the National Socialists in charge of science policy and education to put pressure on his former colleagues and on the organizations in which he was a member. Einstein graciously responded in a letter on 5 June to Max von Laue:

I have learned that my unclear relationship to those German organizations, which still include my name in the list of members, could cause problems for my friends in Germany. For this reason I would like to ask you to make sure that my name is removed from the lists of these organizations. These include, for example, the German Physical Society and the Society des Ordens pour le Merit. I am explicitly empowering you to do this for me. This is probably the right thing to do, so that new theatrical effects can be avoided.

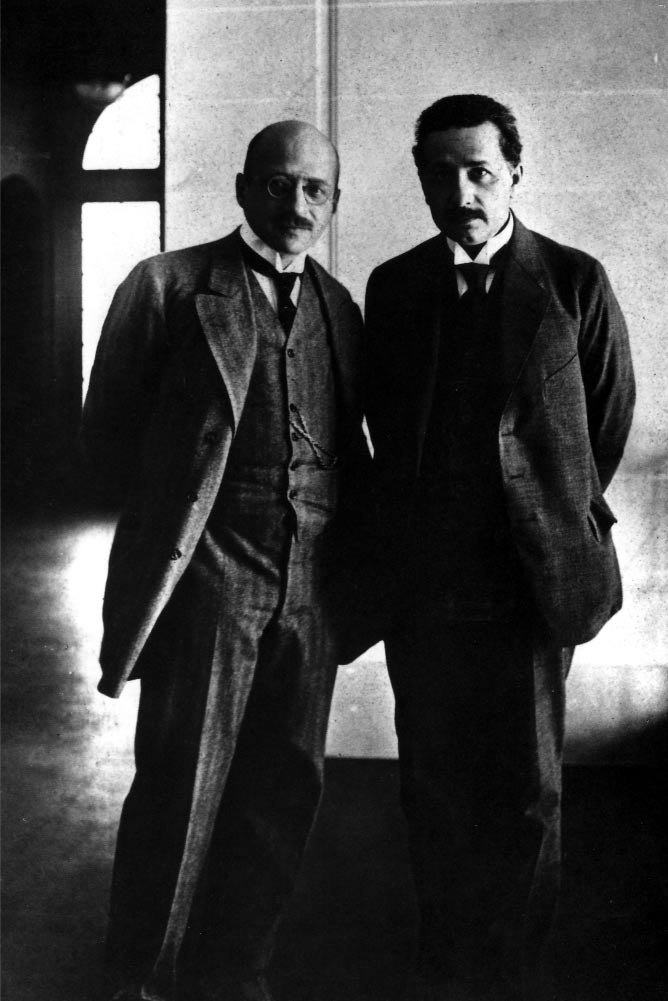

Fritz Haber (1868–1934, left) and Albert Einste in (1879–1955) in 1914. They were both presidents of the German Physical Society, in 1914–1915 and 1916–1918 respectively, and both emigrated in 1933.

ARCHIVES FOR THE HISTORY OF THE MAX PLANCK SOCIETY, BERLIN

Laue replied,

Although I am very thankful that you are trying to make things as easy as possible for us, I nevertheless could not do these two things without the deepest sadness. I hope that, in the not too distant future, the spirits will have calmed down and the German Physical Society will be able to reestablish the connection to you in some form or the other.

He subsequently added,

Because here they hold approximately all German scholars responsible when you do something political.

(The documents quoted here are largely unpublished, but will appear in our forthcoming book, listed at the end of this article.)

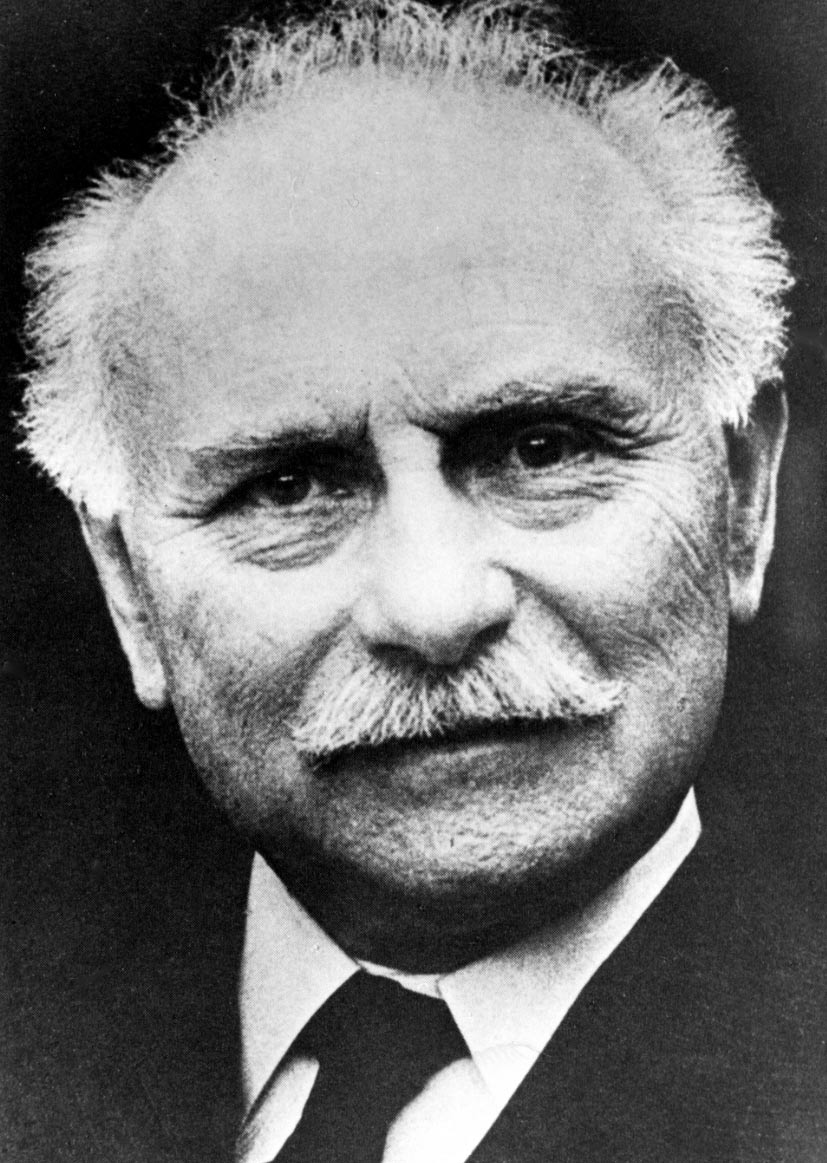

Max von Laue (1879–1960), shown here in the 1920s, opposed Johannes Stark’s attempt to control German physics.

ARCHIVES OF THE GERMAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY, BERLIN

The Prussian Academy of Sciences (PAW) was put under political pressure to throw Einstein out; when it became clear that he had already resigned, the PAW leadership felt obliged to state publicly that they were glad he was gone. In contrast, the DPG barely reacted at all: Einstein’s resignation, like those of the other members who lost their jobs and left Germany, was treated as if it were nothing unusual. In fact, no one was thrown out of the DPG until 1938.

Stark’s attempted coup d’état

Johannes Stark, a key protagonist for “Aryan Physics,” played a brief but important role in the history of the DPG under Hitler. Leading National Socialists at the start of the Third Reich typically used the Führerprinzip (leadership principle), which called for an authoritarian hierarchy, to carve out their own little empires within the “New Germany.” Thus Joseph Goebbels dominated propaganda, Max Amman took over newspaper publishing, and so on. Stark had every right to expect to be successful when he set out to become the “dictator of physics.” As Stark wrote to Philip Lenard, the other leader of Aryan Physics,

Finally the time has come when we can make our conception of science and research count. I used the opportunity presented by my congratulatory letter to Minister [Wilhelm] Frick, whom I know personally, to also let him know that you and I will be happy to advise him with regard to the scientific institutes under his authority.

Early in the Third Reich, Stark, who had given Hitler crucial support during the Weimar Republic, was rewarded with the presidencies of the German Research Foundation (DFG, the main source of research funding) and the Reich Physical-Technical Institute (PTR, analogous to the US’s National Bureau of Standards), one of the best-equipped and most important physics research centers in Germany. Stark introduced the leadership principle at the PTR and also sought to gain control over university appointments, the physics journals, and the DPG itself.

Johannes Stark (1874–1957), here in a photo from the 1920s, tried to become the “dictator of physics” in National Socialist Germany.

ARCHIVES OF THE GERMAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY, BERLIN

Unfortunately for Stark, by making powerful enemies among the National Socialist elite he squandered his influence in Hitler’s Germany almost as soon as he obtained it. Laue also courageously opposed Stark. At the September 1933 physics meeting in Würzburg, during a talk on the organization of physical research in the Third Reich, Stark proclaimed his intentions and announced that the PTR would become the “central executive body” for physics in Germany. But Stark’s talk had been preceded by Laue’s famous version of the story of Galileo, in which he suggestively compared the persecution of Galileo by the Roman Catholic Church to the Aryan Physics campaign led by Stark against Einstein and his physics. As a result, Stark was pushed aside and the industrial physicist Karl Mey, head of research at the Osram Corp, was chosen as the next DPG president.

Subsequently Laue also denied Stark election to the PAW, even though membership was something that Stark, as a Nobel laureate and president of the PTR, had a right to expect. All Stark could do was forbid the PTR staff to function as officials in the DPG. By 1936 Stark had lost his presidency of the DFG; by 1939 he was also forced out of the PTR into retirement. Laue was not disciplined for either his Würzburg talk or his obstruction at the PAW.

The haber memorial

The next and, in a real sense, last act of public dissent that can be attributed to the leadership of the DPG was the so-called Haber Memorial. Before 1933, physical chemist Fritz Haber, Nobel laureate in chemistry for his work on synthetic nitrogen compounds and the man most responsible for the German chemical weapons effort during World War I, was considered a patriot in Germany and branded a war criminal by the Allies. Haber resigned in protest in April 1933 when he was forced to fire the Jewish (which in National Socialist terminology were described as non-Aryan) members of his Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry. Shortly after he left Germany, Haber died in Switzerland. In 1935, a year after his death, the president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Max Planck, decided to hold a memorial ceremony in Haber’s honor. Since Haber had also been a former president and influential member of the DPG, the society joined in sponsoring the event.

National Socialists in the Reich Ministry of Education saw this memorial as a provocation. University professors were instructed not to attend the service, and indeed most stayed away, with some sending their wives in their stead. The ceremony went ahead, with Planck presiding and chemist Otto Hahn and a representative of the armed forces speaking. No officer of the DPG played a leading role in the ceremony, and Hahn himself subsequently thought that the ceremony and his participation in it had weakened his own institute, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry.

The Haber Memorial can be considered an act of defiance—although at the time those involved insisted over and over again that it was not—or at least an attempt to assert a modest amount of independence. Perhaps most significant, it represents the high point of public dissent by scientists against National Socialist policies.

The purge in 1938

During the prewar years of National Socialism, 1933–1939, the tempo and intensity of racism and oppression vacillated dramatically. Low points included the one-day boycott of Jewish businesses in 1933, the subsequent purge of the civil service (and thereby of most scientists) in the same year, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 that declared Jews second-class citizens, and the nationwide Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) pogrom in November 1938. On the other hand, there was an apparent calm after the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in 1934 and an artificial civil peace in 1936 when the Olympics came to Berlin. This back-and-forth of oppression and relaxation produced a gradual resignation of Jewish and foreign members of the DPG. Correspondence between Walther Gerlach and Samuel Goudsmit, a Dutch Jewish physicist who had immigrated to the US, made this situation clear. Gerlach wrote Goudsmit in February 1936,

I would like to discuss another matter with you as well. As a member of the executive committee of the German Physical Society, I learned that you have not paid your membership dues for two years. I can well imagine that you have pecuniary difficulties, but nevertheless would like to ask whether you, as an old institute comrade, respected as a friend and collaborator by many German physicists, do not want to retain your membership. I do not need to add that it personally would especially please me if, along with the personal relationships, the connection through the Physical Society would also be maintained.

Several months later, Goudsmit responded,

Sometimes I see no point in supporting the German Physical Society any longer. The inhuman treatment of many excellent German scientists saddens me very much. I also cannot get used to the idea that I myself am no longer welcome in the Germany I am so fond of. Moreover, while in other countries like Italy and America physics is making great progress, in Germany it has almost stood still.

On the other hand, it was good to know that I still have a few real friends in Germany. The nicest part of my studies was spent in Germany. For these reasons I have finally decided not to abandon my membership completely. You will understand from this letter how difficult this decision was for me.

It is significant that the DPG, in contrast to other scientific professional organizations—for example, those representing mathematicians, chemists, and engineers—only expelled its last Jewish members when forced to do so in 1938. The PAW did the same thing around the same time, and the reason is clear. Those two institutions were not that important for National Socialist science policy. The ones that were considered vital, like the universities, were purged at the very start of the Third Reich.

Along with orders from the Reich Ministry of Education to finally introduce the leadership principle and change the statutes—to get rid of the last non-Aryans and thereby to subordinate the DPG to the full control of the ministry—there was also pressure from below. A few younger members of the DPG—but not adherents of Aryan Physics—tried to push their more conservative elders to better incorporate the society into the National Socialist state. The “young Turks,” all active members of the National Socialist party, included Herbert Stuart, Wilhelm Orthmann, Wilhelm Schütz, and Georg Stetter.

Following the Night of Broken Glass, parallel pressure from Stuart and Orthmann on one side and the Reich Ministry of Education on the other forced the DPG leadership to confront the “non-Aryan question.” The president of the DPG, Dutch physicist and director of the new Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics Peter Debye, handled the matter in the following way:

To the German Members of the German Physical Society:

Given the compelling circumstances, the membership of German Jews as defined by the Nuremberg Laws in the German Physical Society can no longer be sustained.

In agreement with the executive committee, I therefore call upon all members who come under this provision to communicate their resignation from the Society to me.

Heil Hitler!

P. Debye

Chairman

Thus the DPG got rid of its non-Aryan members in what was perhaps a relatively gentle and respectful way—but it got rid of them all the same. Historian Klaus Hentschel’s comparison of the 1938 and 1939 membership lists is available (in German) at http://www.cx.unibe.ch/~khentsch/dpg38-39.html

The planck medal

The highest honor bestowed by the DPG was the Planck Medal for Theoretical Physics. At the start of the Third Reich, the medal became controversial because of its history. It had first been awarded to Planck and Einstein, then subsequently to Niels Bohr, Arnold Sommerfeld, Laue, and Werner Heisenberg—all representatives of the sort of theoretical physics that came under fire after the National Socialists came to power. After Heisenberg received the honor in 1933, the medal was not awarded again until 1937, when Planck himself asked that either the award be resumed or the money used for another purpose.

The next favorites for the medal were Max Born and the Austrian Erwin Schrödinger. Born, a non-Aryan who had resigned his professorship and immigrated to Britain, was out of the question; Schrödinger was Aryan and certainly deserving, but he was also one of the very few German physicists to resign his position when he did not have to. He did not leave in open protest of National Socialist policies, but his departure from Berlin, first to England and later to his homeland of Austria and the University of Graz, was hardly one a physicist would have made under normal circumstances.

Jonathan Zenneck (1871–1959, left) and Karl Mey (1879–1945) at a celebration in honor of Max Planck in 1938.

ARCHIVES OF THE GERMAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY, BERLIN

The DPG leadership hoped to hold its 1937 meeting in Austria, where Schrödinger could attend. Once it became clear that the meeting would have to be held in Germany, DPG officials took up a suggestion from Planck and decided to award the medal to Schrödinger in absentia. The one remaining obstacle was the potential political consequence of such a step. Planck noted that Schrödinger was still listed on the faculty of the University of Berlin, so perhaps there would be no problem, and that in any case the DPG could discreetly ask the ministry if it had any objections. As one DPG member, Clemens Schäfer, pointed out, it was not enough for the ministry to give no response, rather,

I had written to [DPG secretary Walter] Grotrian that, if there were no political misgivings, then I would vote yes. If there were misgivings, then in my opinion no member of the executive committee of the German Physical Society could responsibly vote yes. Thus I am very much in agreement that [acting chairman Jonathan] Zenneck contact the Ministry. However, I do not believe that silence from the Ministry should be taken as agreement. Silence is often sloppiness or—purpose. Thus in the interest of the Physical Society I can only vote yes when the Ministry has explicitly agreed.

Only after the necessary assurances were given, was the medal awarded to Schrödinger.

Thereafter the medal was awarded to deserving physicists, but politics played a persistent role. When asked for nominations, Heisenberg, himself a former Planck Medal laureate, responded in January 1938,

I would like to nominate first of all Pascual Jordan, [of] Rostock, for the Planck Medal, and secondly [Enrico] Fermi. Along with these suggestions I would also like to mention that it does not appear particularly advisable to me to award the next medal to a foreigner. Giving the award to [Louis] de Broglie also does not appear so pressing to me because he already has the Nobel Prize and further honors will not mean so much to him.

On the other hand, I know that at the time, Jordan certainly contributed as much to the discovery of quantum mechanics as did Born. Since at the moment it is not possible to award the medal to Born, and since Jordan’s work is more important than Fermi’s, I would be very pleased if it would be possible to award the medal to Jordan.

What Heisenberg did not mention in his correspondence—indeed, in contrast to comments about Born, what he did not need to mention—was that Jordan was also an enthusiastic National Socialist and his choice would present no political problems. Both the Frenchman de Broglie and the Italian Fermi were proposed to the ministry, but only de Broglie was acceptable because Fermi’s wife was Jewish. The war, and the conflict with the Ministry of Education over the 1938 award, caused another interruption until 1943, when Jordan and Friedrich Hund shared the honor.

The history of the Planck Medal under National Socialism shows how hard the DPG and its officials tried to retain an air of normality in a distinctly abnormal situation, when a medal for excellence in theoretical physics also had to silently accept racist and political criteria as well.

In the service of the National Socialist state

After Debye left Germany and took a visiting position at Cornell University, the DPG young Turks again tried to steer the organization closer to the National Socialist state by nominating Abraham Esau for president in June 1940. Esau was a respected and distinguished technical physicist who had embraced National Socialism in 1933 and had risen to a very influential position in the governmental science policy hierarchy. As the minutes of the June 1940 executive committee meeting relate, however, the old guard managed to hold on to control:

The Chairman [acting chairman Zenneck] proposed that [Carl] Ramsauer be nominated as new chairman of the Society. Stetter proposed Esau. The Chairman objected that Esau has so many other responsibilities that he could not devote himself sufficiently to this task. The Chairman’s proposal was accepted, with Stetter voting against it.

Ramsauer, an industrial physicist at German General Electric (AEG), actively pursued the policy of self-coordination of the DPG to the National Socialist regime and invoked the leadership principle to select his own colleagues on the DPG executive committee. In particular, Ramsauer chose Wolfgang Finkelnburg, an associate professor at the Technical University of Darmstadt. Ramsauer explained why to the respected aeronautical researcher Ludwig Prandtl, who had made an earlier appeal to Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler on behalf of modern theoretical physics. Ramsauer wrote,

As newly elected chairman of the German Physical Society, who according to the new statutes has far-reaching powers, I have selected Prof. Finkelnburg, Darmstadt (soon to be Strasbourg), as vice chairman, mainly because he has personally intervened in a very laudable way for theoretical physics. Moreover, I consider it necessary to have a moderate party member in the executive committee, in order better to be able to handle the more extreme colleagues.

Germany was at war, and Ramsauer took up Prandtl’s lead and worked hard to convince influential leaders in the armed forces and the National Socialist party that physics, including education and basic research, was a vital part of the war effort. In a long memorandum submitted by Ramsauer to the Minister of Education, but actually aimed at leaders in the armed forces and the Ministry of Armaments, Ramsauer argued,

As chairman of the German Physical Society, I consider it my duty to present to you the fears I have for the future of German physics as science and political force. … German physics has lost its previous lead over American physics and is in danger of falling even further behind. … The advances of the Americans are exceptionally great. This is not only because the Americans devote many more resources than we do, rather it has at least as much to do with the fact that they have succeeded in training a numerically large, carefree, and contentedly working young generation of researchers, which are the equals of ours from the best years with regard to their individual performance, and exceed them in their ability to work together. In contrast, on our side more and more we are losing those scientists who gave us our superiority in physics before the world war, and who would be destined to compete with and defeat the Americans.

Ramsauer gave four reasons for the decline of German physics:

The physical institutes of the universities receive in their normal budgets only a fraction of the monies that are now absolutely necessary for the advanced technology used in physical research and teaching. … A large number of capable academic physicists continually labor under the crippling impression that they cannot compete with German industrial laboratories and colleagues in other countries.

Here in Germany one of the main branches of physics, theoretical physics, is being pushed further and further into the background. … This is all the more regrettable since the potential performance of the German spirit in theoretical physics is very great, and precisely here would be a chance in the competition with America, which was originally far behind in this area and had the greatest difficulty in keeping up with us. …

Professorships in physics have not always been given out in accordance with time-tested principle of performance. …

An academic career in physics has lost the appeal it had for our best physicists.

Carl Ramsauer (1879–1955), speaking at the centenary celebration of the German Physical Society, held in 1945 in bombed-out Berlin.

ARCHIVES OF THE GERMAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY, BERLIN

Ramsauer also followed Prandtl’s lead in another way: making his arguments more politically correct in the National Socialist sense. Prandtl had included the following language in a letter to SS leader Himmler on behalf of Heisenberg, who in 1937 had been attacked in the SS weekly Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps) as a “White Jew” and “Jewish in Spirit”:

Of course some non-Aryan researchers were inferior, who trumpeted their Talmud-wares with the peculiar industry of their race. It is good that such products disappear, but among the non-Aryans there are also researchers of the first rank who attempt with great effort to advance science and who in the past truly have advanced it. As an example let me mention Heinrich Hertz, who died young, and with careful and inspired experiments demonstrated the existence of electric waves for the first time, the same waves that today have gained great technical significance for the wireless telegraph and radio. With regard to Einstein, one must distinguish between the person and the physicist. The physicist is through and through first class, but his early fame appears to have gone to his head, so that he has become insufferable as a person. But science cannot concern itself with such personality characteristics. Instead it has to accept the fact that physical laws have been discovered, which in turn have led to further discoveries, and which one cannot leave out without destroying the body of knowledge built upon them.

In his 1942 memorandum, Ramsauer used comparable language:

The justified struggle against the Jew Einstein and against the excrescence of his speculative physics has been transferred to the entire modern theoretical physics and to a large extent has defamed this physics as a product of Jewish spirit.

After the war, Ramsauer published a censored version of this memorandum in Die Physikalische Blätter, in which he cut out without any notice to the reader his now disagreeable language and the connection to the German military–industrial complex.

The DPG in the postwar period

The DPG was dissolved at the end of the war, like all German organizations. It was slowly reconstituted as regional societies in the respective zones of occupation, and in 1951 the western regional societies were merged to reform the DPG. After the fall of communism in 1989, the western and eastern societies merged as well.

During the postwar period, current and former DPG officials emphasized the civil courage of individuals during the National Socialist dictatorship as well as the DPG’s supposed struggle with Aryan Physics. In contrast, they either ignored the collaborative relationship with powerful individuals in the political and military elite or depicted it exclusively in the sense of technocratic innocence. Die Physikalische Blätter, which after 1945 became the quasi-official organ of the DPG, served as the platform in which Ramsauer, Finkelnburg, and Ernst Brüche propagated their excessively positive and misleading version of the history of the DPG under National Socialism. Moreover, the repression of their entanglement in the National Socialist system conformed to the general unwillingness during the early western Federal Republic to take a hard look at the history of Germany under National Socialism.

After the war, the DPG tried to make amends, and enhance its international image: Its leaders contacted some prominent former members who had resigned or were forced to resign in Germany, and some foreign members who had resigned in protest, and asked them to rejoin. In 1948 the Max Planck Medal was demonstratively given to Born at one of the first meetings of the DPG in the British zone. During the following years, the medal was also given remarkably often to emigrants. It was harder to reintegrate into the society the members who had been excluded or who had resigned. Of course, individuals who rejoined were welcomed, but it took several years before the society apologized to those colleagues as a group and officially invited them to rejoin. The most prominent former member, Einstein, could not be persuaded to rejoin, although during the 1950s he did nominate candidates for the Max Planck Medal once again. In a letter to Laue, one of the very few German colleagues Einstein respected both during the Third Reich and after the war, he gently begged off his invitation to the Berlin Physical Society’s 50th anniversary celebration of the theory of relativity:

Age and sickness have made it impossible for me to participate in such occasions and I must admit that this divine command has been a little liberating for me. For everything that has to do with a cult of personality has been embarrassing for me. In this case even more, for it is a matter of an intellectual development that many were very significantly involved in, a development that is far from being over. Thus I have decided not to attend any of these events, several of which have been planned in different places.

If I have learned one thing by pondering over a long life, it is this, that we are further removed from a deeper insight into the elementary processes than most of our contemporaries believe (not including you), so that noisy celebrations have little to do with the actual state of affairs.

References

1. Alan Beyerchen, Scientists Under Hitler: Politics and the Physics Community in the Third Reich, Yale U. Press, New Haven, CT (1977).

2. David Cassidy, Uncertainty: The Life and Science of Werner Heisenberg, Freeman, New York (1992).

3. Klaus Hentschel, Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Birkhäuser, Boston (1996).

4. Dieter Hoffmann, “Between Autonomy and Accommodation: The German Physical Society in the Third Reich,” Physics in Perspective (in press).

5. Dieter Hoffmann, Mark Walker, eds., Zwischen Autonomie und Anpassung. Die Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft im Dritten Reich, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany (in press).

6. Mark Walker, Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the German Atomic Bomb, Perseus, New York (1995).

More about the authors

Dieter Hoffmann (dh@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de

Dieter Hoffmann, 1(dh@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de) Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, Germany .

Mark Walker, 2(walkerm@union.edu) Union College, Schenectady, New York, US .