The evolution of hadron-collider experiments

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2010

In particle-physics experiments, the discovery of increasingly more massive particles has brought deep understanding of the basic constituents of matter and the fundamental forces between them. Such discoveries are made possible by accelerator beams of ever more energetic particles.

Traditionally, such beams were directed at stationary targets. In that configuration, however, the total center-of-mass energy Ecm of a collision between a beam particle of energy Eb and a target particle grows only like √

One can get much more bang (Ecm) for the buck (Eb) by making counterpropagating particle beams collide head-on. In that case, Ecm grows much faster; for beams of equal mass and energy, it’s simply 2Eb. For almost half a century now, such colliding-beam accelerators—colliders—have been hurling beams of hadrons (protons, antiprotons, nuclei) or leptons (electrons, positrons) at each other with increasing vehemence.

In this article, we focus on hadron colliders and particularly on the experimental techniques that have evolved with them. Their crowning achievement to date is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, whose proton beams last year achieved an Ecm of 8 TeV, almost ten thousand times the 0.9-GeV mass of the proton. That collision energy sufficed to reveal a new particle that’s very likely to be the long-awaited Higgs boson (see Physics Today, September 2012, page 12

Beginnings

The first hadron collider was the 1-km-circumference proton–proton (pp) Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), 1 commissioned at CERN in 1971. Its beam energies ranged from 12 to 31 GeV. Experimenters set up particle detectors at eight points where the two countercirculating beams crossed each other. Experiments at the ISR revealed the logarithmic rise of the pp total scattering cross section at energies where it was expected to have leveled off. But the detectors were not, at first, adequately configured to study collisions that produced particles with large momentum components, pT, transverse to the collision axis. Only later was it fully realized how important high-pT events are for revealing new physics.

Ten years later, CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), until then a fixed-target accelerator, became the Sp

The two countercirculating beams were tethered in the collider’s 7-km-circumference tunnel by an array of 1.3-T bending magnets. By the end of 1983, the collaborations that ran the large UA1 and UA2 detectors at the collider’s beam-crossing points had discovered the heavy W± and Z0 bosons that mediate the weak interactions. 3

Before the end of the decade, Fermilab’s p

The LHC’s design Ecm is 14 TeV. Confining the 7-TeV proton beams to a preexisting 27-km tunnel necessitated the challenging development of 8.3-T superconducting bending magnets. 5 But before LHC construction began in 1998, there was a painful interlude across the ocean. The planned 87-km tunnel of the Superconducting Super Collider, a 40-TeV pp collider, was already under construction near Dallas, Texas, when that project was abruptly canceled by the US Congress in 1993.

Luminosity

Collision energy Ecm is by no means the whole story. The frequency of particle collisions must be high enough to yield significant numbers of interesting events, even for rare processes with minuscule cross sections. Total pp and

A crucial figure of merit for the collision rate at a beam-crossing point is the luminosity L, given by the event rate per unit scattering cross section. For example, if L is 106/(mb s) at a beam crossing in a collider, that crossing will produce a total of about 108 collisions every second. Luminosity depends on a beam’s diameter and current, and on how well the exquisitely thin collider beams are aimed at each other. Typically, L improves with time and experience.

Luminosity integrated over time determines how many rare events an extended collider run can record. It is often appropriate to quote integrated luminosity in events per femtobarn. A run of several months at one of the LHC detectors might produce an integrated luminosity of 10 fb−1. Such a run, encompassing 1015 pp collisions, would be expected to record only a few hundred Higgs bosons with discernible decay modes.

Detectors

Particle detectors at hadron collider detectors have evolved in size and complexity as technology has advanced and physics questions have changed. Each generation of detectors has built on previous experience. The size increases reflect both higher energies and the need for greater sophistication.

The early ISR experiments had rather specific physics goals that were addressed with detector designs still influenced by the fixed-target era. They offered only limited solid-angle coverage. But toward the end of the ISR period, the anticipation of new discoveries stimulated a new detector paradigm. One now had to study new massive, short-lived particles like the W and Z bosons and the top quark, all very much heavier than the proton. Their decay particles emerge over a large angular region, usually with large pT. That required detectors with more complete angular coverage.

So, starting with the Sp

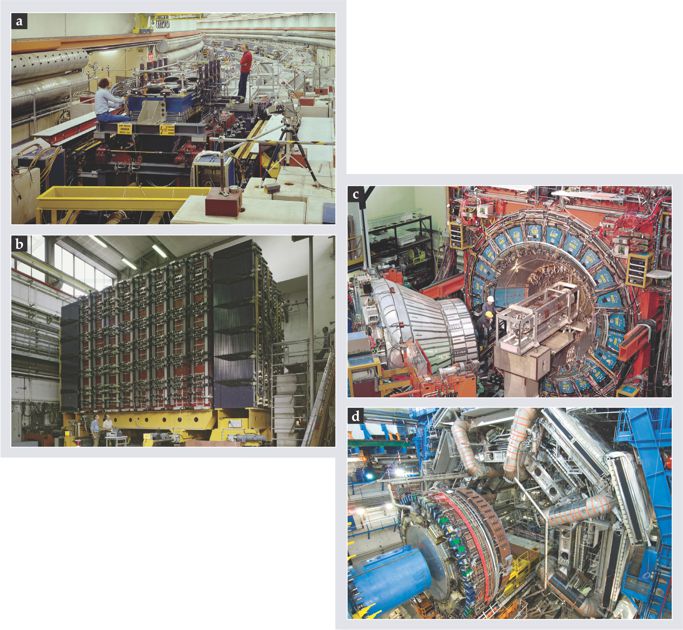

Detector designs varied, depending on the physics emphasis and the available technology. Figure 1 gives a sense of the evolution and variety of collider detectors. Trackers have evolved from multiwire and drift chambers that measured ionization trails with resolutions of a few hundred microns, to silicon-microstrip and pixelated detectors with micron resolution. That much-finer resolution makes possible the measurement of tiny distances between the production and decay points of the very short-lived, heavy-quark hadrons that often identify rare processes.

Figure 1. Evolution of detectors that record collisions at hadron colliders. (a) The 6-m-diameter detector of the R702 experiment at CERN’s Intersecting Storage Rings

To optimize the measurement of telltale transverse momenta, many collider detectors get their magnetic fields from a surrounding solenoid aligned with the beam axis. Field intensities have increased from about 1 T in early collider days to 4 T in the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) at the LHC.

6

(See the cover

Calorimeters are designed to measure the energies of hadrons, electrons, and photons by fully containing and recording the energy they lose in showering cascades of collisions as they stop in absorbing material. Because showers generated by hadrons are typically much bigger than those generated by electrons and photons, electromagnetic and hadron calorimeters require quite different designs.

So-called sampling calorimeters alternate absorbing layers with layers of transparent plastic scintillator or ionizing liquid whose signals are proportional to the energy of the traversing particle. Alternatives to such layered configurations are calorimeters made entirely of scintillating crystals.

Muons, the only charged particles that survive beyond the calorimeters, are usually identified in surrounding low-cost ionization detectors. The almost complete solid-angle coverage by calorimeters and muon detectors in modern detectors makes it possible to spot “missing” transverse energy carried away by high-energy neutrinos—or by something altogether new.

Keeping up with collision rates

With increased luminosity, total collision rates grew from 105 per second at the Sp

Therefore, complex trigger systems have evolved to select the relative handful of potentially interesting events from the flood of all collisions. Reliable triggering is essential because a rejected event is lost forever. At the Sp

Despite the challenging demands of the very high LHC luminosities, ATLAS and CMS, the collider’s two large general-purpose detectors, have refined multi-level triggering to achieve efficient and manageable event-logging rates of a few hundred per second, with only about 1% dead time.

The changing physics landscape

Interesting high-energy collisions between hadrons are best understood as interactions between a constituent quark or gluon (collectively called partons) in one hadron with a parton in the other. Quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of those strong interactions, can—in principle—predict the wide array of possible outcomes. When a head-on parton collision produces a large-angle scattering, QCD’s paradoxically increasing force with increasing separation prevents partons from emerging as free particles.

Instead, quarks and gluons scattered in head-on parton–parton collisions manifest themselves at the detectors as “jets,” collimated sprays of hadrons. Predicted by QCD, jets were hinted at in ISR data. But then the Sp

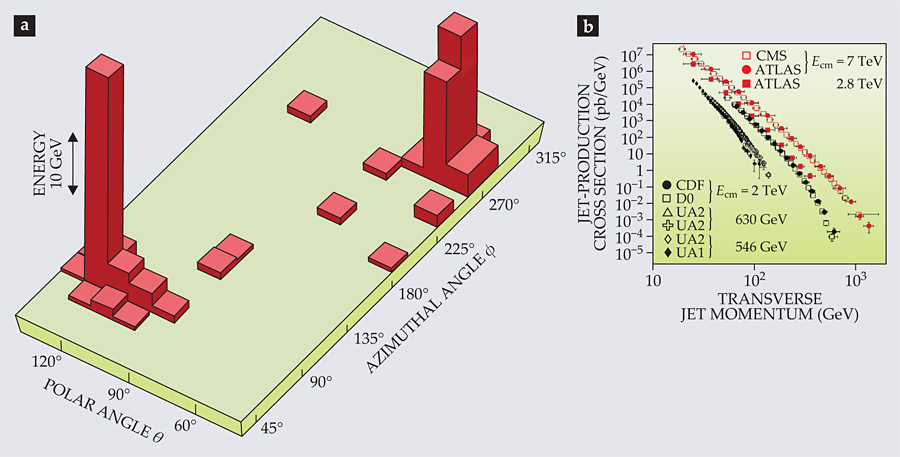

Figure 2. Jets of hadrons produced in high-energy collisions. (a) The angular distribution of energy deposited in the segmented calorimeter of the UA2 detector at the Sp

Measured over 10 orders of magnitude at increasing Ecm, the differential cross section for the production of high-pT jets, plotted in figure 2b, is in excellent agreement with QCD calculations. Those cross sections provide a detailed look at the momentum distributions of different partons within the proton. 7 The most energetic jets arise from quarks or gluons that happened to be carrying about half of the incident proton’s momentum—much more than their fair share.

The search for the W± and Z0 bosons predicted by unified electroweak theory was the primary motivation for building the Sp

W± → ℓ±ν and Z → ℓ+ ℓ−,

where ν denotes a neutrino, gave convincing evidence that hadron colliders are indeed great discovery tools. The discoveries demonstrated, in particular, the usefulness of missing transverse energy for indirectly measuring an escaping neutrino’s pT. The missing-energy signature also played a major role in the discovery of the top quark (t) at the Tevatron collider in 1995. And it is now a mainstay in the search for dark matter at colliders.

Following the handful of W and Z events seen by the UA1 and UA2 detector teams at the Sp

In the early 1990s, the top quark was urgently sought as the sixth and last quark required by the standard model. Null results had made it clear that it was very much heavier than the 5-GeV bottom quark (b). The Sp

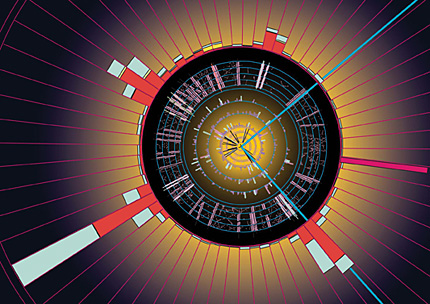

The CDF and D0 teams measured mt to be 173.2 GeV, nearly the mass of a gold nucleus. Unlike the five lighter quarks, the top quark decays (mostly to W + b) before it has had time to dress itself in hadronic garb. The impressively small 0.5% uncertainty in mt underscores the modern capacity for precision measurements in complex production and decay topologies involving hadron jets, charged leptons, and undetectable neutrinos. A typical t

Figure 3. Beam’s-eye view of a top–antitop quark pair created at the center of the Tevatron’s D0 detector. One top quark decays to a W boson plus a bottom (b) quark, and that W promptly decays to a muon plus a neutrino. The other top quark also decays to W + b, but that W decays into two quarks that emerge as jets of hadrons at 8 and 10 o’clock. The lengths of the histogram bars around the cylindrical detector represent energy deposited by jets in azimuthal calorimeter segments surrounding the detector’s inner tracking layers. The isolated blue line at 2 o’clock is the W-decay muon, and the jet encompassing the muon at 4 o’clock was generated by the decay of a b quark. The magenta bar at 3 o’clock indicates the missing energy and direction of the escaped neutrino.

Cross-section measurements for the production of b quarks were first done at the Sp

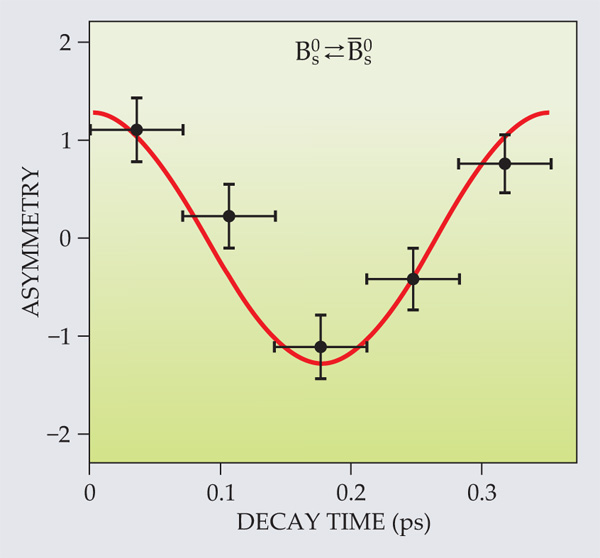

Such oscillation arises from the fact that the quark-flavor eigenstates of the mesons are linear superpositions of mass eigenstates with slightly different masses. At the Tevatron, the CDF and D0 teams collected large samples of neutral B mesons with decay lengths accurately determined in silicon-strip vertex detectors. Thus the teams were able to measure the very rapid (0.3-ps) oscillation of B0s mesons, a subclass of B mesons that also carry strange quarks. 11 The CDF result is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. Neutral Bs mesons oscillate between states B0s and

At the LHC, not only ATLAS and CMS but also the smaller LHCb detector, dedicated to b-quark physics, continue flavor-oscillation investigations with huge samples of B mesons. That superabundance permits searches for extremely rare B-decay modes that would be sensitive to new physics beyond the standard model. The new physics might, for example, elucidate the observed predominance of matter over antimatter in our universe (see the article by Helen Quinn in Physics Today, February 2003, page 30

For decades the search for the Higgs boson (H) has been a primary goal of hadron-collider experiments. It drove the designs for ATLAS and CMS, which have to cope with many rare collision signatures embedded in a huge background of ordinary hadronic debris. The much-heralded 125-GeV boson announced by the ATLAS and CMS teams 13 last 4 July has not yet exhibited any departure from standard-model predictions for the Higgs boson.

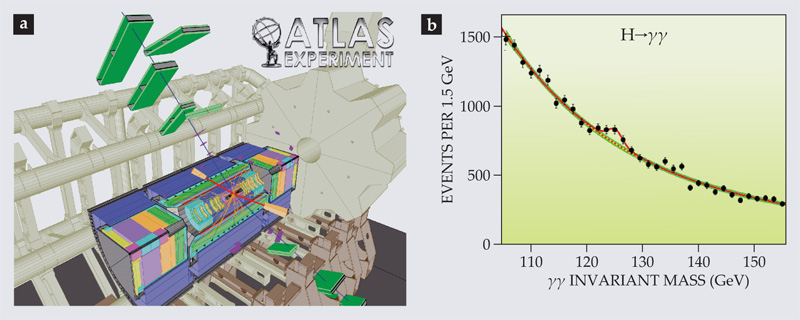

That discovery was a giant experimental step toward the completion of the standard model. Figure 5 shows a rare candidate in ATLAS for the low-background decay mode

Figure 5. Searching for the Higgs boson at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.

H → Z0Z0 → e+e−μ+μ−.

The figure also shows the CMS’s evidence for the more abundant two-photon decay mode H → γγ.

The Higgs discovery at the LHC exploited innovative analysis techniques developed at the Tevatron collider. In fact, corroborating evidence was found

14

in D0 and CDF for H → b

The standard model leaves fundamental questions open: What is the particle nature of dark matter (see Physics Today, May 2013, page 14

Theoretical suggestions for new physics beyond the standard model abound, each with proposed experimental signatures. A prominent example is supersymmetry, in which each standard-model boson is partnered with a new fermion—and vice versa. Supersymmetry could solve several of the standard model’s problems and provide a plausible dark-matter particle. The need to search for supersymmetric particles set important benchmarks for the design of the LHC detectors.

In searches for new high-mass phenomena, the key is the increase of Ecm. As yet, the colliders have yielded no definitive evidence of new physics beyond the standard model. But the scheduled 2015 increase in the LHC collision energy to its design value of 14 TeV holds out great hope for early sightings of terra incognita.

Analysis tools

Computing and communication tools have been revolutionized over the past four decades. The ISR experiments were analyzed on large mainframe computers. Their limited processing speeds and storage-disk capacity forced a certain simplicity in algorithms for reconstructing collision events. At the Tevatron and the LHC, computing advances brought fundamental changes that made it possible to decipher complex decay patterns despite the presence of hundreds of background particles.

A typical LHC event generates a megabyte of information. Although collider experiments have contributed importantly to computing advances such as massively parallel processing and grid computing, the progress of high-energy physics rests squarely on the advances made by the computing industry.

The advent of fast and cheap field-programmable gate arrays, digital-signal processors, and microprocessors has made possible the migration of computer intelligence to the detectors themselves. The detectors can now perform smart event selection and full reconstruction in real time. Those capabilities also allow the efficient collection of special event samples used for calibrations in situ.

Lasers and position monitors make it possible to align detector components with micron precision. Microprocessor farms, having replaced mainframe computers for offline analyses, allow parallel processing of events that keeps up with the data flood. Large storage disks hold massive calibration databases that significantly improve detector resolution.

In the later Tevatron runs and at the LHC, distributed-grid computing 15 has permitted globally connected farms to generate large sets of simulated Monte Carlo events. The event-simulation programs have become remarkably sophisticated. The yearly volume of data, real and simulated, produced by ATLAS and CMS reaches tens of petabytes.

The increasing complexity of experiments has necessitated new analysis tools. Sophisticated new algorithms improve particle tracking by recognizing true tracks in the presence of noise. Multivariate pattern-recognition algorithms now identify electrons and photons on the basis of the shapes and correlations of energy deposits in finely segmented calorimeters. New “particle flow” methods rely on high-precision tracking measurements of charged-particle momenta instead of calorimeter measurements and thus improve the determination of jet energies.

As physics goals have turned toward finding increasingly rare processes in the face of huge backgrounds, the old methods of simply selecting events based on a set of basic kinematic variables have become too inefficient. New multivariate techniques such as neural networks and decision trees have become common.

16

Although the use of such algorithms initially met with skepticism, they have been shown to be reliable and very useful. And new statistical techniques, based on both frequentist and Bayesian methods, have become commonplace for combining many related measurements and minimizing the impact of systematic uncertainties (see the article by Louis Lyons in Physics Today, July 2012, page 45

Collaborations

Hadron-collider collaborations have grown spectacularly in four decades. Typical experimental collaborations at the ISR in the early 1970s were consortia of a dozen or so physicists from a few institutes. By the early 1980s, the largest ISR experiment involved some 90 scientists from 16 institutes. The UA1 experiment at the Sp

At the Tevatron that trend continued. The CDF and D0 collaborations each brought together about 600 scientists, and they marked the beginning of the large-scale globalization of high-energy physics experiments. For example, D0 involved 81 institutions in 18 countries on 4 continents.

Globalization became even more pronounced at the LHC. The ATLAS and CMS collaborations each have about 3000 scientists from some 200 institutions in about 40 countries. About one-third of the scientists are students, and many more are PhD physicists in their early careers. Those statistics underline the educational value of front-line science activity and its value in fostering understanding of how to work productively with colleagues from different backgrounds. The collaborations and the host laboratories have made conscious efforts to include scientists from emerging nations.

At the ISR and the earlier, fixed-target accelerators, collaborations ran with a minimum of formal organization. Decisions were made at frequent meetings of all the participating physicists. But with the growing sizes, complexities, and costs of experiments, it became necessary to formalize collaboration rules and working structures. On one hand, the collaborations are nowadays internally organized from the bottom up by democratically established bodies and working groups, with elected spokespersons and written governance documents. On the other hand, relationships with the host laboratories, collaborating institutions, and funding agencies are formalized with memoranda of understanding that specify rights and obligations of all partners in a top-down manner.

Each of the giant collaborations comprises many distinct projects for design, building, software development, and physics analysis. The experiments have evolved rather complex organizational structures, with coordinators at various levels to ensure that the parts fit together smoothly. But the real work on individual projects is typically carried out by groups of relatively few individuals working closely together, just as in the early days of high-energy physics.

Geographical dispersion brought the need for new communications mechanisms. In the old days, physicists had to be on site to interact effectively with colleagues. But in the early 1980s, the internet revolution introduced new collaboration modes. Electronic messaging meant that physicists in far-flung locations could exchange information quickly. Although periodic face-to-face gatherings remained necessary, electronic communication made it possible for distant collaborators to conduct complex, ongoing analyses. By the turn of the millennium, videoconferencing further buttressed collaboration at a distance. A typical collaboration discusses progress by conducting dozens of video meetings on most days, hampered only by the wide disparity of time zones.

The Sp

Modern high-energy-physics collaborations are peculiar organizations in that they are self-organized around common goals, but with no traditional authority for setting salaries or conducting formal employee reviews. And yet they have been enormously successful in articulating goals and mobilizing the requisite effort over time spans measured in decades. Loyalty to the experiment often transcends loyalty to the employing institution. It is not uncommon for individuals to pass from graduate student to permanent scientist with several sequential employers while working on a single experiment. The collider collaborations also have distinct personalities, typically formed in their very early days and persisting even after the early participants have left the scene.

The increasingly large and complex hadron-collider experiments have brought many challenges, but the lessons learned from successive generations of experiments have made possible remarkable advances in our understanding of Nature. Big science is here to stay.

References

1. K. Johnsen, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70, 619 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.70.2.619

2. C. Rubbia, P. McIntyre, D. Cline, in Proceedings of the International Neutrino Conference, Aachen 1976, H. Faissner, H. Reithler, P. Zerwas, eds., Vieweg, Braunschweig, Germany (1977), p. 683;

J. Gareyte, in 11th International Conference on High-Energy Accelerators, Geneva, Switzerland, July 7-11, 1980, W. S. Newman, ed., Birkhauser, Basel, Switzerland (1980), p. 79.3. G. Arnison et al. (UA1 collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 122, 103 (1983); https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91177-2

G. Arnison et al. (UA1 collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 126, 398 (1983); https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90188-0

M. Banner et al. (UA2 collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 122, 476 (1983); https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91605-2

P. Bagnaia et al. (UA2 collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 129, 130 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90744-X4. H. T. Edwards, Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 35, 605 (1985); https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.35.120185.003133

S. Holmes, R. S. Moore, V. Shiltsev, J. Instrum. 6, T08001 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/6/08/T080015. L. Evans, P. Bryant, eds., J. Instrum. 3, S08001 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08001

6. S. Chatrchyan et al. (CMS collaboration), J. Instrum. 3, S08004 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08004

7. A. A. Bhatti, D. Lincoln, Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 60, 267 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.012809.104430

8. T. Aaltonen et al. (CDF collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 151803 (2012); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.151803

V. M. Abazov et al. (D0 collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 151804 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.1518049. F. Abe et al. (CDF collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2626 (1995); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2626

S. Abachi et al. (D0 collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2632 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.263210. V. M. Abazov et al. (D0 collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 092001 (2009); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.092001

T. Aaltonen et al. (CDF collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 092002 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.09200211. V. M. Abazov et al. (D0 collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 021802 (2006); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.021802

A. Abulencia et al. (CDF collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 242003 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.24200312. R. Aaij et al. (LHCb collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 101803 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.101803

13. G. Aad et al. (ATLAS collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 716, 1 (2012); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.020

S. Chatrchyan et al. (CMS collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 716, 30 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.021

See also the review by M. Della Negra, P. Jenni, T. S. Virdee, Science 338, 1560 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.123082714. T. Aaltonen et al. (CDF and D0 collaborations), Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 071804 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.071804

15. J. Harvey, P. Mato, L. Robertson, in The Large Hadron Collider: A Marvel of Technology, L. Evans, ed., EPFL Press, Lausanne, Switzerland (2009), p. 229.

16. P. C. Bhat, Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 61, 281 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.012809.104427

17. C. Albajar et al. (UA1 collaboration), Z. Phys. C 48, 1 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01565600

18. G. Aad et al. (ATLAS collaboration), J. Instrum. 3, S08003 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08003

More about the authors

Paul Grannis is a Distinguished Research Professor of physics at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Peter Jenni was a senior physicist at CERN in Geneva. He is now a guest scientist at the University of Freiburg in Germany.