Special Issue: Hans Bethe

DOI: 10.1063/1.2138417

There are a handful of people who soar, whose accomplishments are so off-scale as to nearly defy belief. Hans Bethe (2 July 1906-6 March 2005) was of that caliber. As just one measure of his stature, imagine the task of copying his published opus by hand, for that is how he wrote most of it; an industrious scribe would labor for many years without even tackling his innumerable government studies and reports. This quantitative dimension would be un-remarkable were it not that the mountain of paper would contain seams of previously unknown intellectual gold, nuggets of ingenious invention, brilliant syntheses of new knowledge, technical analyses that altered the geopolitical landscape, and calls to keep morality in mind.

This issue of Physics Today breathes life into the preceding paragraph with articles that sketch Hans’s contributions to most, but certainly not all, of the areas in which he played such seminal roles for more than 70 years. Appearing in roughly chronological order,

-

▸ Silvan Schweber writes (beginning on page 38) on the period before World War II—Hans’s education, swift rise to international prominence, emigration to the United States, and impact on American physics;

-

▸ The late John Bahcall and Edwin Salpeter discuss (page 44) Hans’s work on energy production in stars, nuclear astrophysics in general, and neutrino physics;

-

▸ Freeman Dyson relates (page 48) the history of Hans and quantum electrodynamics, both before the war and, later, after the discovery of the Lamb shift;

-

▸ Richard Garwin and I describe (page 52) Hans’s long involvement with national defense—the Manhattan Project, the hydrogen bomb, the cold war, and arms control;

-

▸ John Negele tells (page 58) of Hans, the nuclear many-body problem, and nuclear matter; and

-

▸ Gerald Brown gives us (page 62) an intimate look at his remarkable collaboration with Hans on supernovae and other astrophysical topics, in the last decades of Bethe’s life.

We provide an overview of Hans’s accomplishments and offer glimpses of the talents and erudition that made it all possible. These talents and erudition can easily be inferred from the scientific literature itself. But that literature cannot describe his personality and character. The authors of these articles, all having had the good fortune to enjoy long and unforgettable friendships with Hans, have sought to offer some insights into how it came to be that he had so special a place in the hearts and minds of his colleagues and of the community at large—a respect and esteem that are not explicable solely in terms of his tangible contributions to scientific knowledge and the public good.

A fuller picture

In an effort to give a fuller picture of the man, I add a few words to what you will find in the articles that follow.

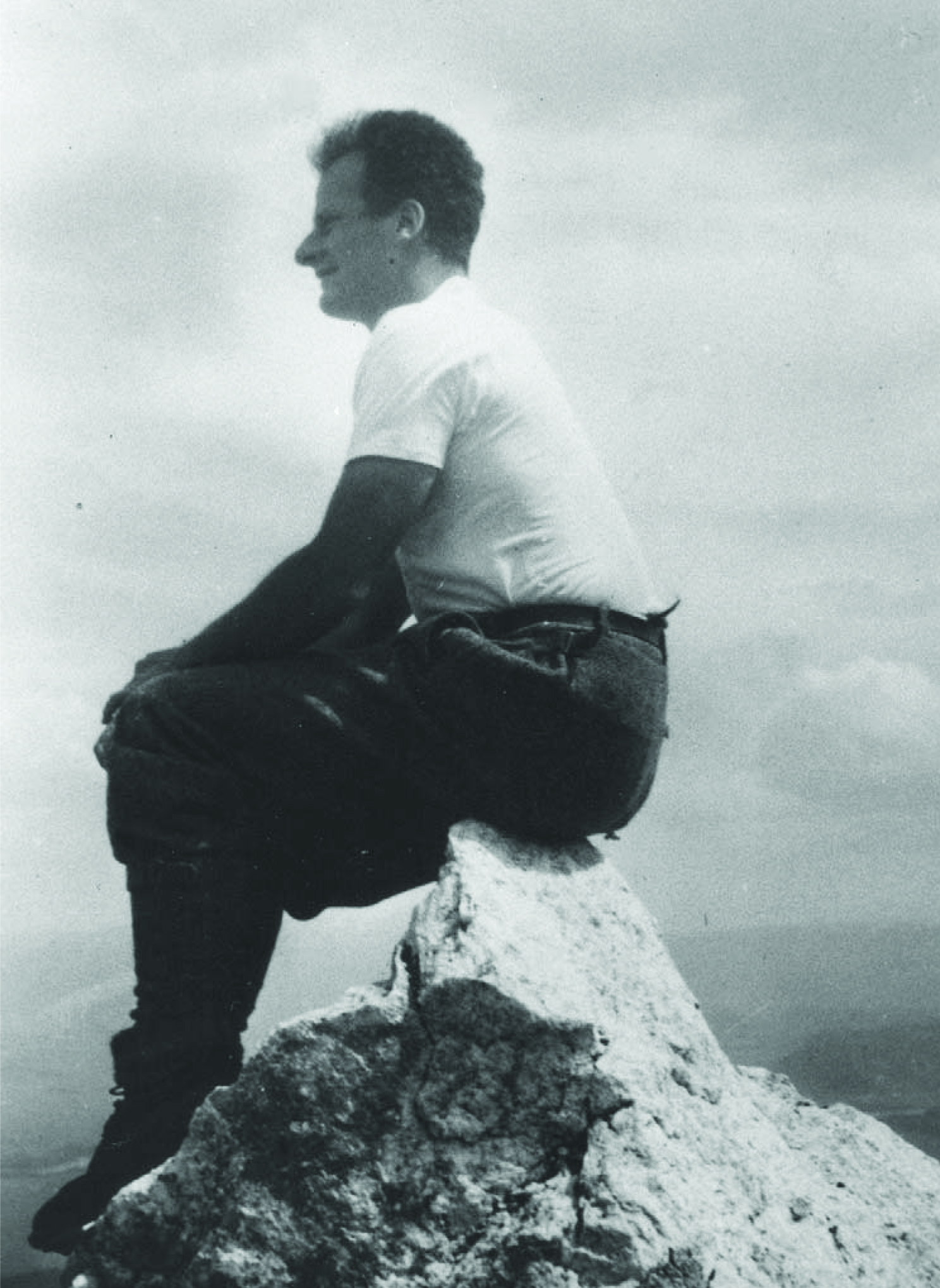

Hans loved nature and the outdoors—he was a very strong man physically, and until late in life, he hiked over distances and at altitudes that few of his contemporaries could match. At Cornell, he would take a roundabout route to lunch if the flowers were in bloom. But his self-discipline was daunting—in a discussion in his office he would always be fully focused on the topic at hand, but if you looked over your shoulder as you left he would already be writing on his stack of paper. If the air conditioning broke down in the heat of summer, he would have a fan brought in.

Hans had a great sense of humor and a resonant laugh. He made sure that his Selected Works (World Scientific, 1997) included the “scandal” of his youth—the spoof of Eddington described by Sam Schweber in his article. And late in life he liked to quote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s line “Oh, to be 80 again.” With a twinkle in his eye, he once told me that he had just told Senate staff that he could not testify at an important hearing if it were postponed by a few hours, because of a prior commitment; what he had not told them was that the engagement was a dinner with his former student Leonard Maximon. Students at all levels—from high school to PhD candidates—were a high priority for him and they always found him available.

Hans was an unassuming man—anything but a prima donna. Once during lunch with him and Victor Weisskopf, the conversation led Viki to say that a particular physicist was habitually arrogant toward his colleagues, and I agreed. Hans was astonished—“Gosh! He’s never been that way with me.” Viki and I just looked at each other silently, and then Hans blushed a bit and quietly cleared his throat.

Nevertheless, Hans had an objective evaluation of his off-scale talents and strengths, combined with a clear recognition that he was not a magician like Paul Dirac. And he was competitive—he once told a younger colleague that one should only work on problems for which one had an unfair advantage!

To the end, he was a seeker of new knowledge, devoted to actually doing science. Well into his nineties, in conversations about his work with Gerry Brown, he continued to display a stunning command of physics—his strong voice moving steadily within a few sentences from shock waves to neutrino interactions to thermodynamics.

Hans in the Alps, where he would go for a week or two every summer before he emigrated to the US. This photo is circa 1930.

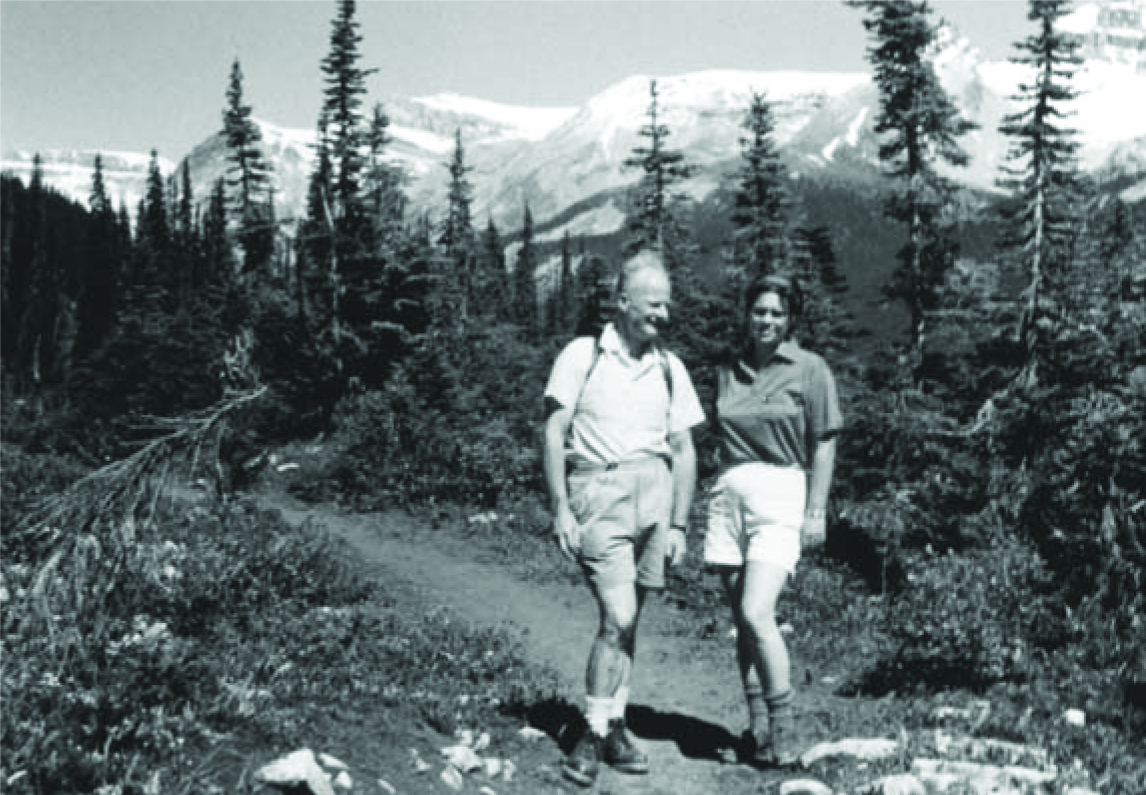

(All photos courtesy of Rose Bethe.)

Hans in his office at Cornell, circa 1935-36.

Hans and Rose Bethe in the Canadian Rockies in the summer of 1959.

For almost seven decades, his wife Rose was his con stant companion and closest adviser. Together, they explored the Rocky Mountains in the summers before Pearl Harbor. In the difficult decisions that Hans faced during the controversies surrounding the H-bomb, it was primarily with Rose that he discussed how to deal with the unprecedented moral dilemmas that arose. In the last years of his life, as his physical strength ebbed, it was Rose and their son Henry who kept him abreast of the political scene, which distressed him deeply, and who made it possible for him to continue to participate in public policy debates and to satisfy his unquenchable curiosity.

More about the authors

Kurt Gottfried is an emeritus professor of physics at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Kurt Gottfried, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, US .