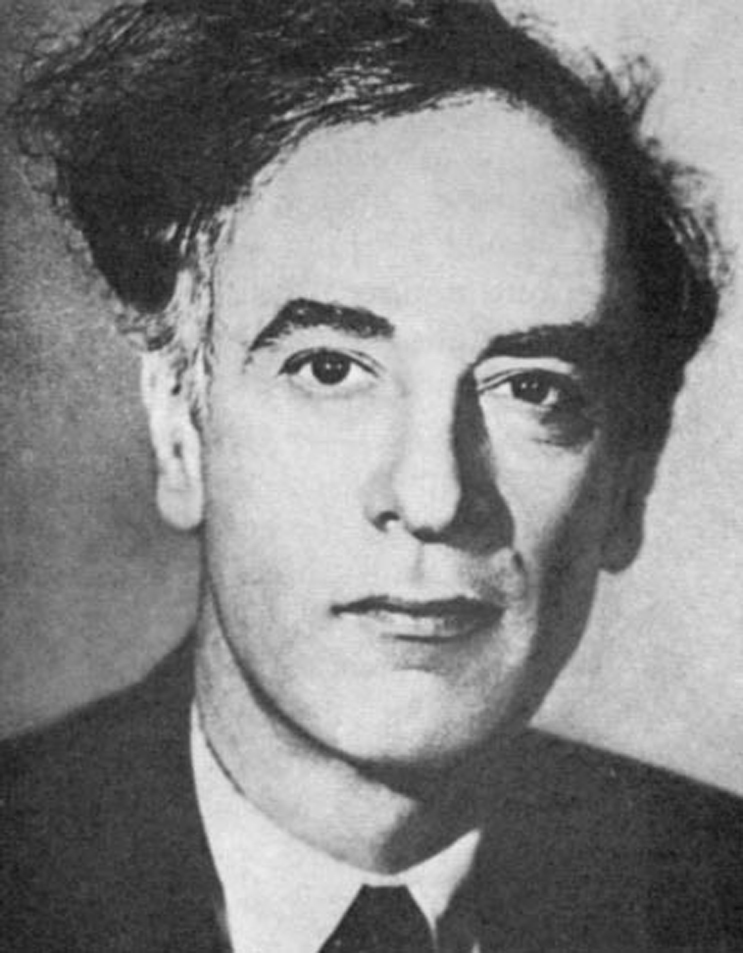

Lev Davidovich Landau, Soviet Physicist and Nobel Laureate

DOI: 10.1063/1.2408530

On 1 April, Lev Davidovich Landau, Soviet Nobel Prize winner, died in Moscow at the age of 60. He had never fully recovered from injuries sustained in an automobile accident six years ago.

Landau

Landau was born on 22 January 1908 in the city of Baku on the Caspian Sea. At 14 he entered Baku University, and two years later transferred to the University of Leningrad, where at 19 he received his doctorate in 1927. This period marked the beginning of his scientific writings when, in 1927, he introduced the concept of the density matrix for energy. After spending two years at the Leningrad Physicotechnical Institute, where he worked on the theory of the magnetic electron and on quantum electrodynamics, he went abroad in 1929.

For a year and a half, he studied at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen, and also in Germany, England, and Switzerland. Through collaboration with the leading theoretical physicists of that time, Landau developed the wide scope of interest that characterized his career. His association with Niels Bohr was of particular importance in this development; Landau regarded himself as a pupil of Bohr. While still abroad, in 1930, he published his classic work on the diamagnetism of electrons in a metal (Landau diamagnetism), which later led to the explanation of magnetic susceptibilities of metals at low temperatures in strong magnetic fields (de Haas–van Alphén effect).

Shortly after his return to Leningrad, he went to the Ukranian Physicotechnical Institute in Kharkov and headed the theoretical section from 1932 to 1937. During this period, in collaboration with Evgeny Lifshitz, Landau began the now famous series of monographs on theoretical physics.

In 1937, he was appointed head of the theoretical section of the Institute for Physical Problems in Moscow. He was jailed for a year in 1938 as a German spy and was released only after Peter Kapitsa protested personally to the Kremlin.

At the institute, his interest turned to the problem of superfluidity of liquid helium then being investigated experimentally by Kapitsa. Landau published his theory explaining the properties of helium II in 1941. As a consequence of his interpretation, Landau was able to predict the existence of the “second-sound” mode of wave propagation in helium II; second sound was observed experimentally in 1944. In the 1950s, he developed a general theory of the quantum Fermi liquid that predicted a number of phenomena in He3, among which was the existence of a “zero sound.” For these investigations on condensed matter, Landau was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962.

Landau was elected an active member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and had been awarded the Stalin Prize three times (once in 1941 for his theory of liquid helium and work on phase transitions). He was elected to membership in the Danish and Dutch Academies of Science, as a foreign member of the Royal Society of London and of the US National Academy of Sciences.

When Landau died, Physics Today was preparing to publish the following two pieces about him. The first is a tribute by Academician Vitaly Ginzburg, written to celebrate Landau’s 60th birthday, and the second is an interview with Landau. Both were submitted by the Novosti Press Agency.

Ginzburg, who has done research at the Physics Institute in Moscow since 1940, is professor of physics at Gorkii State University. In 1953, he became a corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.